Trauma-Informed Strategies for Supporting Youth in the Juvenile Justice System during COVID-19

This brief provides guidance for juvenile justice (JJ) administrators and staff to promote healing and increase the likelihood of resilience among youth, despite the many adversities associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and their involvement in the JJ system.

Resilience among youth involved the juvenile justice system

Juvenile justice services include community supervision (probation or parole), as well as institutional placement of youth in juvenile jails or prisons. Only about one quarter of adjudicated youth are placed in out-of-home care. Youth in the JJ system vary considerably in terms of both risk (including those who pose little risk to public safety and others who pose considerable risk) and needs (including youth with little need for therapeutic intervention and those with considerable need).

Many youth in juvenile justice—especially those in institutional settings—have experienced significant childhood adversity and trauma. System involvement and certain JJ system practices can increase psychological distress; these practices include searches or pat-downs, the use of physical restraints, and out-of-home placement. Black, Hispanic, and Native American youth are historically overrepresented in the JJ system due to systemic inequities in law enforcement, rates of institutionalization, and biases in decision-making processes; they are also more likely to have experienced trauma due, in large part, to structural racism and historical trauma. Girls comprise a minority of JJ youth, but are more likely to have suffered considerable adversity, to have preexisting mental health issues, and to meet the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis.

The good news is that decades of research on resilience shows that protective factors can help youth thrive in the face of trauma and adversity. Although youth who are exposed to trauma are at greater risk for negative impacts on their brain development (e.g., responding to threat cues, managing emotions like anxiety and anger), as well as mental health and physical health problems over the life course, it is essential that JJ administrators and staff recognize the strengths and potential of all youth to succeed in life. Rather than focus on risk and deficits (e.g., “What’s wrong with you?”), JJ agencies should focus on the experiences that led to trauma (e.g., “What happened to you?”); agency staff should also help youth build on their strengths and leverage these to recover, heal, and lead fulfilling lives (e.g., “What’s right with you?”).

Download

Key terms

Trauma is one possible outcome of exposure to adversity. Trauma occurs when a person perceives an event or set of circumstances as extremely frightening, harmful, or threatening—either emotionally, physically, or both.

Adversity is a broad term that refers to a wide range of circumstances or events that pose a serious threat to a youth’s physical or psychological well-being.

Resilience is the process of positive adaptation to adversity that arises through interactions between individuals and their environments.

Pandemic is an outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area and affects an exceptionally high proportion of the population.

To promote positive outcomes among youth in the JJ system, it is essential to first understand that they are not “doomed” to poor life outcomes. Research affirms that certain types of supports are especially likely to help youth thrive after traumatic experiences such as pandemics. In fact, a number of evidence-based interventions and approaches can mitigate the negative effects of trauma and positively impact brain development. Studies with youth involved in JJ have shown that up to 40 percent improve their emotional and behavioral functioning and strengths in the first year after entering services in systems of care. Among the most important factors in promoting resilience to trauma and supporting healthy brain development is having at least one reliable, nurturing caregiver.

In addition, it is critical to ensure that youth can access inclusive supports that are sensitive and responsive to their race, ethnicity, gender, gender orientation, and LGBTQIA+ identity. For staff to serve youth most effectively, it is essential that they become more aware of their own biases and attitudes; enhance their knowledge about youth experiences, beliefs, and values; and increasing their comfort and skills in talking to youth about the role of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation in service delivery. Establishing culturally responsive practices can mitigate the effects of disparity and disproportionality that persist in the JJ system. These practices include collecting and analyzing data to inform structured decision making in JJ, developing community-based alternatives to residential placement, enhancing culturally and linguistically informed services, and improving relationships between youth and law enforcement.

Finally, JJ agencies must have appropriate knowledge of and sensitivity to the potential impact of trauma on the well-being of youth, and should adopt a trauma-informed approach to JJ service provision.

Effects of COVID-19 on the juvenile justice system

COVID-19 presents considerable challenges for JJ systems to support both youth under community supervision and those in institutional confinement. JJ system leaders and staff can also take important steps to help youth involved in the system thrive. These youth, like all of their peers, experience adversities and trauma from COVID-19, including the fear of illness or death of one’s self or loved ones or the actual loss of loved ones and social supports. Additionally, institutionalized youth may lose contact with family members or access to other social supports and may experience an additional reduction in supports such as in-person mental health services. While a considerable number of youth have been released from juvenile detention as a result of COVID-19, youth who remain in detention are disproportionately Black and Latinx (compared to before the pandemic). Youth under community supervision may experience disruption to life events (e.g., employment, graduations, education) and difficulty adhering to reporting requirements (e.g., lack of in-person visits with probation or parole officers, loss of employment, or reduced employment hours). Moreover, staff serving youth in the JJ system also face challenges due to COVID-19, including an inability to serve youth in-person; the need to quickly adapt procedures and policies; worry and concern over their own health and safety; and secondary stress and vicarious traumatization for the experiences of friends, family, and youth under their custody.

Fortunately, research shows that a trauma-informed approach to promoting resilience to disasters and pandemics can be highly effective. Identifying and providing supports that promote youth emotional development and healing is a critical part of pandemic preparedness and response for JJ systems.

A trauma-informed juvenile justice system to promote resilience and healing

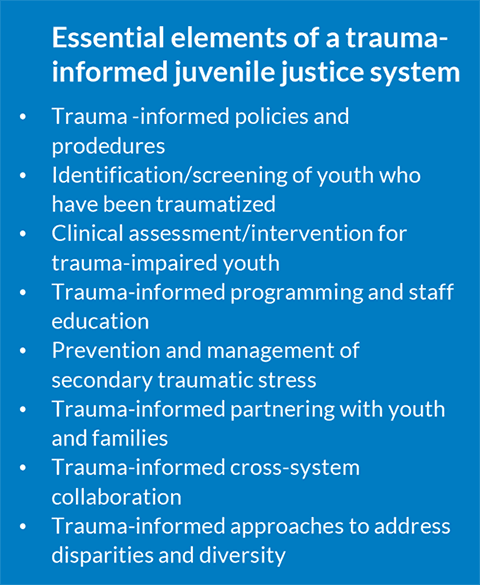

JJ systems that are trauma-informed are better equipped to support the safety and emotional well-being of youth. A system that is trauma-informed adheres to four key principles: 1) The system realizes the widespread impact of trauma and potential paths for recovery; 2) it recognizes the signs and symptoms of clients, families, staff, and others involved in the system; 3) it responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and 4) it seeks to actively resist re-traumatization. Although trauma training for JJ leadership and staff is critical, broad systemic shifts in daily operations and service delivery are also needed for JJ agencies to be truly trauma-informed. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network identifies essential elements of a trauma-informed JJ system:

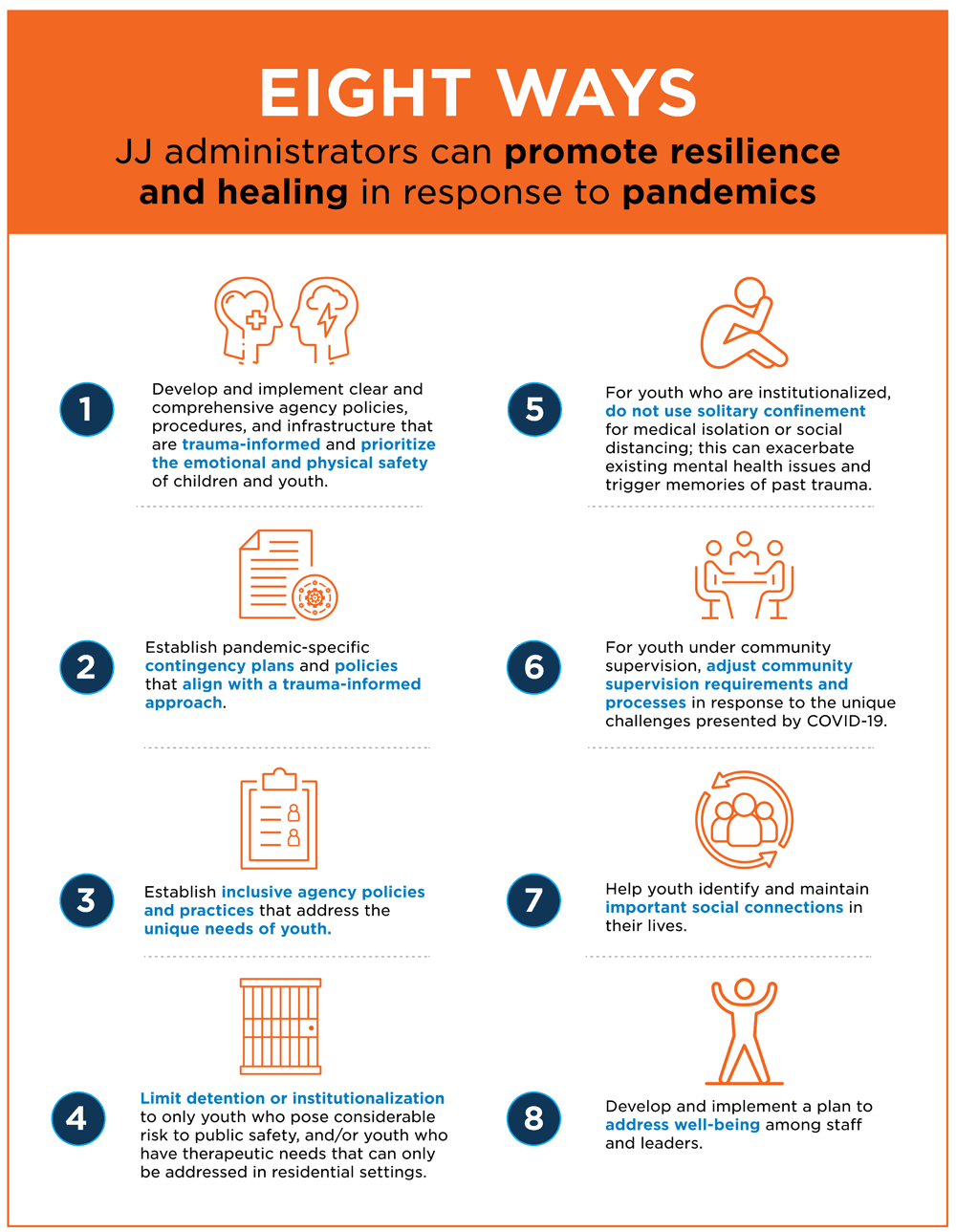

The infographic below offers eight ways for JJ administrators to mitigate pandemic-related trauma and support resilience in youth affected by COVID-19.

Eight ways JJ administrators can promote resilience and healing in response to pandemics

1. Develop and implement clear and comprehensive agency policies, procedures, and infrastructure that are trauma-informed and prioritize the emotional and physical safety of youth.

- Implement trauma curricula across JJ corrections and community supervision staff (including supervisors)—and across partnering community agencies—to ensure a common language and coordinated response for addressing youth trauma (e.g., Psychological First Aid, Skills for Psychological Recovery, Think Trauma).

- Include universal trauma screening for youth involved in JJ to identify trauma and related psychological and behavioral issues. Use an effective screening tool—one that is valid, reliable, and age- and culturally-sensitive; that assesses adversities both at home (e.g., child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, parental substance abuse or mental illness, domestic violence) and in the community (i.e., social determinants of health, such as poverty, community violence, natural disasters and pandemics); and that assesses both exposure to adversity (types) and trauma symptoms (reactions). Consider using a tool adapted for pandemics (e.g., UCLA Brief COVID-19 Screen for Child/Adolescent PTSD).

- Develop formal partnerships with community service organizations, including a system for referral and follow-up and a plan to reduce structural and social barriers to accessing evidence-based and evidence-informed trauma and mental health interventions. These partnerships will enable JJ staff to quickly and effectively address youth’s and families’ emotional and basic needs.

2. Establish pandemic-specific contingency plans and policies that align with a trauma-informed approach.

- Ensure that disaster planning addresses youth trauma and offers pandemic-specific guidance for risk assessment and case planning.

- Engage in cross-system collaboration with other national, state, and local youth- and family-serving organizations and emergency systems (e.g., Red Cross, FEMA, law enforcement, schools) to coordinate a trauma-informed response. Identify common agency missions or shared agency goals and improve information sharing and resource coordination.

- Establish a technology infrastructure and reduce systems barriers to virtual visits and service delivery (e.g., billing restrictions, mobile device access and use).

- Closely monitor changes in federal, state, and county JJ policies designed to address pandemic-related challenges and support youth and staff well-being.

3. Establish inclusive agency policies and practices that address the unique needs of youth.

- Provide training for staff and leaders on trauma and cultural competence, as well as inclusion strategies for reducing and eliminating individual and institutional bias based on race, ethnicity, class, gender, and gender orientation.

- Recognize the disproportionate rates of COVID-19 infections within communities of color – particularly Black people – and the higher resulting rates of pandemic-related trauma among youth of color.

- Partner with youth to learn about their background, identity, and orientation (cultural, sexual, gender) and integrate a culturally inclusive, LGTBQIA+ responsive approach to JJ services that supports and affirms their values, beliefs, and strengths.

- Establish a plan for supporting families in under-resourced communities during a pandemic.

4. Limit detention or institutionalization to only youth who pose considerable risk to public safety, and/or youth who have therapeutic needs that can only be addressed in residential settings.

“I need to see my therapist in-person. During the pandemic, I’m not able to have my in-person therapy sessions, so it’s really weird for me. We can do it online, but it’s not the same, especially if I need to say something about other people in the house. Because in my old foster home, I had no support.”

“In one respect, the pandemic has caused the residential numbers to go down for safety reasons. But I think that kids are better off not being placed in residential settings to begin with. And so that could result in better consequences as an unintended response to the COVID-19 pandemic and maybe will lead to a more permanent shift in philosophy of when the kids really need to be in residential facilities and when they don’t, and how we integrate more of a trauma response.”

- With reductions and changes to services during the pandemic, the benefit from institutionalization for youth may be considerably diminished. At the same time, congregate care can increase the risk that COVID-19 will spread among youth and staff.

- Establish policies and practices that accurately identify both the risks and needs of youth and reduce secure detention and residential placement as much as possible for those who can instead be supervised in the community

5. For youth who are institutionalized, do not use solitary confinement for medical isolation or social distancing; this can exacerbate existing mental health issues and trigger memories of past trauma.

- Allow for healthy means of social distancing, such as increased time outdoors and staggered meals.

- Identify supportive and therapeutic activities for youth when group activities cannot be adapted to fit social distancing and health guidelines.

- Establish safety and health procedures within JJ facilities and provide resources such as COVID-19 testing, soap and hygiene products, and cleaning products.

6. For youth under community supervision, adjust community supervision requirements and processes in response to the unique challenges presented by COVID-19.

- Reduce reporting requirements concerning the frequency of meetings with probation and parole officers, as well as mandatory drug testing.

- When replacing in-person visits with video technology, maintain the structure and content of regular meetings as much as possible and show patience as youth adjust to new modes of meetings.

- Modify school, employment, and program participation requirements to those that can be safely and successfully met by youth during COVID-19.

- Limit probation or parole revocations for failure to adhere to technical conditions of community supervision that do not pose public safety risks.

- Find new and flexible supports and activities for youth that are consistent with public health guidelines (e.g., help youth overcome barriers to accessing supports due to the pandemic, such as distance learning, utilizing telehealth appointments, and applying for unemployment).

7. Help youth identify and maintain important social connections in their lives.

- Support and help maintain social connections between youth and their families, friends, and communities to provide social support and ongoing information about their safety.

- For youth in institutional settings, identify creative methods (and flexibility in agency operations) to help them connect with family members, peers, attorneys, and other social supports (e.g., increased virtual visits and emails).

- Tailor strategies to the youth’s age and developmental stage.

8. Develop and implement a plan to address well-being among staff and leaders.

“I think the community and the juvenile detention facilities have tried to accommodate visitation and family connections for the youths who are detained by greater use of technology for video visitation kinds of approaches.”

“In order to help [youth], professionals need to understand what trauma is and how it impacts not only the kids, but [themselves], because there are so many professionals in the system who have not addressed their own trauma, whether it be adverse childhood experiences, COVID-19, racial discrimination, or other [experiences].”

- Formalize strategies for preventing, identifying, and addressing secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma among JJ staff and leaders by creating a workforce wellness plan that promotes high-quality, trauma-informed services and reduces staff burnout and turnover.

- Increase staff members’ awareness of the potential impacts of working with traumatized individuals on their own well-being, and emphasize the importance of prioritizing self-care (e.g., mindfulness, exercise, good nutrition, rest, social support, therapy) during the pandemic.

- Screen for secondary traumatic stress among staff (Professional Quality of Life Measure, Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale) and in the organization (e.g., Secondary Traumatic Stress Informed Organization Assessment); offer information for obtaining support as needed.

Additional Resources for Supporting Youth in the JJ System During COVID-19

- Trauma-Informed Court Self-Assessment (National Child Traumatic Stress Network)

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in the Juvenile Justice System (Annie E. Casey Foundation)

- Transforming Juvenile Probation: A Vision for Getting It Right (Annie E. Casey Foundation)

- Leading with Race to Reimagine Youth Justice (Annie E. Casey Foundation)

- Considering Childhood Trauma in the JJ System (American Bar Association)

- The Essential Elements for Providing Trauma-Informed Services for Justice-Involved Youth and Families (National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges)

- Creating Trauma-Sensitive Communities (The Annie E. Casey Foundation)

- Trauma Among Girls in the Juvenile Justice System (National Child Traumatic Stress Network)

- Bridging Research and Practice Project to Advance Juvenile Justice and Safety (Urban Institute)

Acknowledgements and disclaimer

This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support, particularly Mildred Johnson, but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this brief are those of the author(s) alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation. We also thank the youth and juvenile justice staff who participated in focus groups and key informant interviews to inform this brief.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube