Creating Policies to Better Serve Diverse AANHPI Populations

Authors

Sunny Sun, Astha Patel, Jing Tang, Tracy Gebhart, and Yiyu Chen contributed equally to writing this brief

While Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) populations are, collectively, the fastest-growing racial group in the United States, these groups have rich and distinctive experiences and their unique challenges are not adequately supported by current policies; this lack of support is especially evident for AANHPI children and their families. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many challenges among AANHPI children and families. In this brief, we first highlight the diversity and growth of various AANHPI populations and review some challenges that these populations face. Then, we share a new analysis that highlights the distribution of AANHPI children and families across the country. Finally, we highlight policies and programs that leaders in states with high proportions of AANHPI children should consider adopting to better support their unique needs.

Context

AANHPI populations represent the fastest-growing and most economically divided racial group in the United States, with the AA population growing by 81 percent from 2000 to 2019 and NHPI populations experiencing 61 percent growth during the same period. However, the umbrella term “AANHPI” represents more than 50 ethnic groups with distinct languages, cultures, and histories. These diverse populations include Tongans raising families in Salt Lake City, Filipino Americans thriving in Philadelphia, and Indian Americans residing in the bustling neighborhoods of central New Jersey. Despite their increasing populations and diversity, AANHPI populations are also understudied and underrepresented in research.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, AANHPI children and families faced a significant surge in economic hardships, racialized violence, adverse health outcomes, and discrimination-related mental health issues. For instance, the Federal Bureau of Investigation reported a staggering 77 percent surge in hate crimes against Asians in 2020 across the United States (compared to the previous year). Stop AAPI Hate, a coalition working to end violence and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), also reported 10,905 hate incidents targeting AAPI individuals from March 2020 to December 2021. Some data also show that the pandemic may have disproportionately impacted certain AANHPI subpopulations. For example, NHPIs (Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders) in Utah experienced the highest COVID-19 hospitalization rates among all ethnic groups, with 141 per 1,000 cases compared to the statewide average of 83.3.

These challenges reflect longstanding structural inequalities and patterns of discrimination, including colonization and immigration policies that continue to impact AANHPI populations such as the U.S. government’s annexation of Hawaii in 1898 without the consent of the Hawaiian sovereign government; the Immigration Act of 1924, which barred people from Asian countries from immigrating to the United States; and the U.S. military’s seizure of land from the CHamoru people in Guam for military bases.

A note to readers

Research with and on Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) populations is lacking, which hinders our understanding and ability to support these populations. While AA, NH, and PI families have rich, unique experiences that should be represented in research to inform better, more targeted and supportive policies, data on these population are often combined instead of disaggregated due to Census categories and smaller populations, which conceals differences and inequities among the groups. Astute readers will notice that our analysis here treats AANHPI populations as a combined group because no better data exist. We hope these findings, which show the scale and geographic scope of AANHPI populations, underscore the importance of creating research and policies that recognize their diversity.

Findings

The rapid rise in AANHPI populations has been driven by a substantial increase in Asian American people due to the revocation of exclusionary immigration policies and the Refugee Act of 1980; these shifts have been accompanied by movement of NHPI people through out-migration from the Pacific Islands and Hawaii for economic reasons, which has diversified the location of AANHPI children and families beyond traditional geographic concentrations. Our analysis of 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates examines child populations in every state and finds that:

Nationally, nearly 3.7 million children under age 18 are AANHPI.

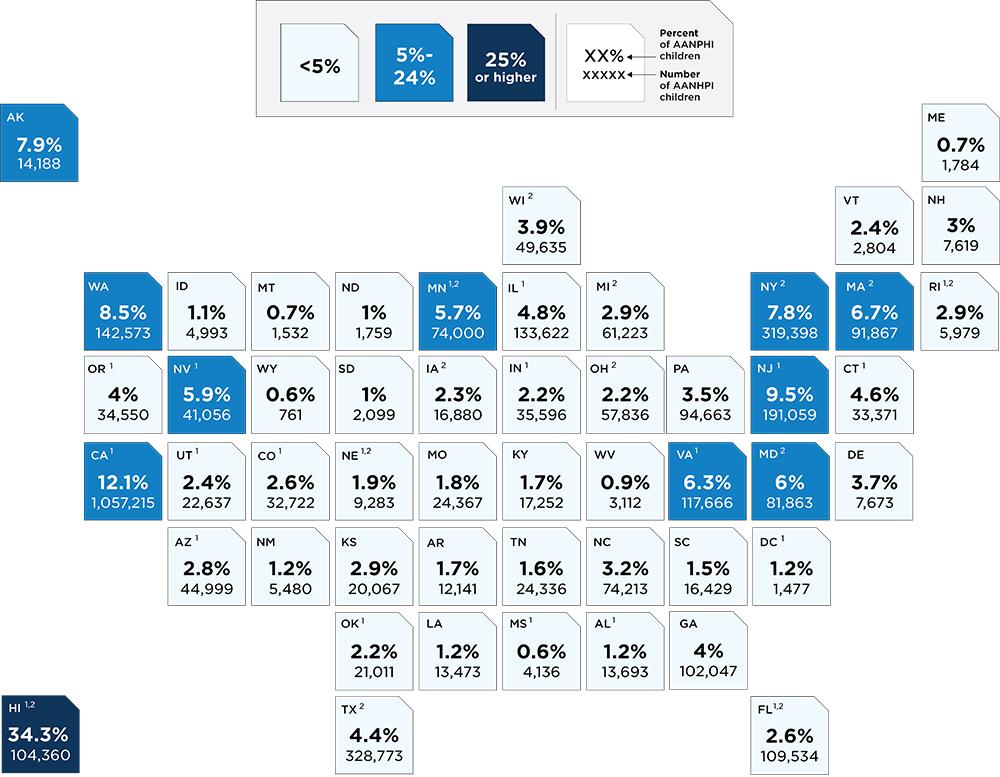

- Nationally, nearly 3.7 million (5.0%) of children under age 18 are AANHPI, ranging from just 0.6 percent of children in Wyoming and Mississippi to 34.3 percent of children in Hawaii.

- More than one in five states have a higher proportion of AANHPI children than the national average: Hawaii, California, New Jersey, Washington, Alaska, New York, Massachusetts, Virginia, Maryland, Nevada, and Minnesota.

- The greatest total number of AANHPI children live in California (1,057,215) and Texas (328,773).

This growing population of AANHPI children has unique and diverse experiences at home.

- For example, our analysis found that the vast majority of AANHPI children live in households with at least one foreign-born parent (85.6%) and more than one third live in households in which at least one parent does not have U.S. citizenship (40.4%).

More than one third of AANHPI children live in households in which at least one parent does not have U.S. citizenship.

Percentage and total number of child population that is AANHPI, by state

Sources: Populations estimates are derived from authors’ analysis of Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) 2021 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year estimates. AAPI curriculum status identified by Kerr, E., Tse, S., Gu, J. & Tse, J-M. (2022). AAPI and Ethnic Studies Requirements for K-12 Students in America’s Public Schools [White paper]. New York, NY: Committee of 100.

Notes: AANHPI Children = Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals under age 18 identified as Chinese, Japanese, or Other Asian or Pacific Islander in the 2021 ACS. Children identified as Hispanic or multiracial, in addition to AANHPI, are not included in AANHPI estimates.

1. State has statutes that require a statewide K-12 Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) studies curriculum or includes AAPI studies in their K-12 academic standards.

2. State has introduced legislation to require AAPI studies in K-12.

Policies to Support AANHPI Children and Families

We recommend that policymakers across the country create and implement policies that address the specific needs and circumstances of AANHPI children and families, with implementation strategies responsive to unique challenges and opportunities. Below is a sampling of research-backed state policies that can serve as models for consideration in other states.

Culturally responsive learning

In some states, culturally responsive learning experiences for AANHPI children have been incorporated into K-12 education. Illinois became the first state to require an AAPI1 studies curriculum through a standalone bill, ahead of states with more sizable AANHPI communities (only 5% of Illinois’ child population identified as AANHPI in 2021; the above map). As of August 2022, 10 states had statutes that required statewide AAPI studies curricula and 12 states and the District of Columbia included AAPI studies in their academic standards (together, these 22 states and the District of Columbia are identified using superscript 1 on the above map); 13 states had introduced legislation to require AAPI studies (superscript 2 on the above map).

Related Content

- Meeting Indigenous Parenting Students' Needs Promotes Equity in Higher Ed

- Federal Policies That Contribute to Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities and Potential Solutions for Indigenous Children, Families, and Communities

- Researchers’ Experiences Inform Recommendations for Funders to Facilitate Racial Equity in Research

In Hawaii, where 26.4 percent of the population identifies as Native Hawaiian (alone and in combination with other races), the state Constitutional Convention in 1978 recognized the detrimental impacts of colonization and assimilation policies on Native Hawaiian language and culture and called for “comprehensive Hawaiian education program consisting of language, culture and history…[in]…public schools.” AAPI studies are also important, for AANHPI and non-AANPHI students alike, to better understand complex histories, combat troubling perceptions, and create more supportive learning environments. For these curricula to have the intended impact, states must ensure dedicated funding streams and equitable review of lesson content.

Targeted support for inclusion and language access

Several broad federal policies are intended for populations that include AANHPI children and families, including those designed to support immigrant, refugee, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and limited English proficiency (LEP) families. As states implement these policies, they can do so in ways that directly address the unique circumstances of AANHPI populations.

We offer one example: States receiving funding for child care subsidies through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) are required to provide consumer education materials to help households with lower incomes make informed child care and early education (CCEE) choices and improve their knowledge of child care and child development. Providing these materials in multiple languages and tailoring distribution to immigrant or LEP communities can expand knowledge of CCEE among key AANHPI populations and improve their decision-making agency. Additionally, Head Start grantees, for instance, are required to support dual language learners by supporting children’s home languages in the classroom and creating welcoming environments that incorporate the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of families in the community. Effective implementation of policies that support dual language learners can be especially important to AANHPI children—many of whom are dual language learners who need both English and home language support to effectively participate in school and achieve academic success.

Conclusion

AANHPI children represent a rapidly growing population with diverse experiences and unique needs and assets. To advance equity for AANHPI communities, state governments should partner with AANHPI populations to review their existing policies and center these populations’ voices to create and advance culturally affirming, equity-centered policies.

A Note About Terminology and Data

Footnote

1 We use the term AAPI, rather than AANHPI, to reflect the language used in most curriculum bills introduced in these states.

Suggested Citation

Sun, S., Patel, A., Tang, J., Gebhart, T., Chen, Y., & Gordon, H.S.J. (2023). Creating policies to better serve diverse AANHPI populations. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/1803h2803u

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube