Two-Generation Programs May Have Long-term Benefits, According to Simulation

Child care and early education programs to enhance the development of preschoolers are widespread, as are programs to enhance the education, training, and labor market opportunities of adults. Increasingly, family well-being researchers and practitioners recognize the value of strategically and intentionally combining these goals in two-generation programs. Such programs serve both parents and their children and, while many have provided parallel (but separate) services to children and their parents (sometimes called 1.0 programs), more recent programs seek to coordinate the services provided to parents and those provided to their children through early child care centers (sometimes called 2.0 programs). That is, more recent two-generation intervention strategies seek to enhance parents’ social and economic capital, as well as the development of infants and toddlers, through coordinated services and programming.

While several evaluations have explored the effects of two-generation interventions, most have only examined effects over a short time period. This brief adds a longer-term focus to the discussion by drawing on a simulation (the Social Genome Model, or SGM; see more information below) that estimates potential long-term effects of the two-generation program model by projecting later life outcomes for the children whose families participate in these programs. To understand the life course implications of high-quality two-generation programs, we simulated the effects on children’s later outcomes of accessing two-generation programs that serve both low-income parents and their children (birth to age 4). That is, for preschool children whose families’ incomes are below 200 percent of the federal poverty line, we estimated what their long-term outcomes would be if they had access to a high-quality two-generation program. Simulated changes were implemented only during the preschool years.

We find that having access to high-quality two-generation programs can have positive effects on children’s outcomes that mostly persist throughout the time these children are in school. We also find modest but significant increases in higher education enrollment, earnings, and lifetime income as children become adults, particularly for Black people.

Learn more about the Social Genome Model

About our simulation

Our simulation uses the SGM to examine the potential effects of services, resources, and programs provided as part of two-generation programs that combine education and training for parents with early childhood education programs for children. These programs’ connections to free or low-cost early childhood education address some of the barriers to educational progress that low-income parents face, including inadequate access to reliable child care and lack of social support. More recent programs offer high-quality classrooms, family supportive services, local partnerships that bring together employers and workers, and postsecondary education and/or workforce development, all in a coordinated manner.

We ran two different simulations: one that uses the short-term impacts of programs such as the Enhanced Version of Early Head Start with employment services and Tulsa’s Career Advance—two successful two-generation programs—and another “aspirational” simulation, which assumes that newer 2.0 versions of the two-generation programs can lead to larger improvements in children’s cognitive abilities and parental education than current research has indicated is possible.

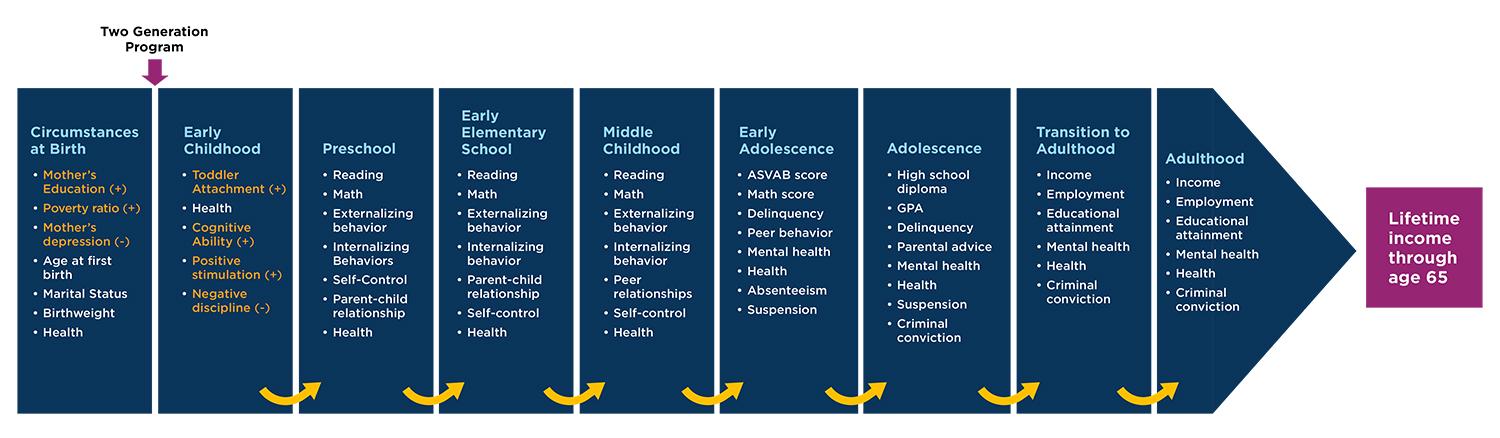

Before running the simulations, we first drew on evaluation studies that assess the effectiveness of two-generation programs. In these studies, we identified a range of program impacts and then identified similar measures to use in the Social Genome Model. Specifically, we simulated changes in mothers’ educational levels, family income (poverty level at the child’s birth), children’s cognitive ability, toddlers’ attachment, mothers’ depression levels, positive parent-child stimulation practices, and negative discipline practices (see Figure 1).

For the first simulation, which only uses the effect sizes of evaluated programs, we relied on the improvements found in the research studies that use measures similar to those found in the Social Genome Model. (See Appendix A for a full list of outcomes identified, the equivalent measures in the SGM, the studies reviewed, and the effect sizes.) For the second, aspirational simulation, we simulated the same improvements but used larger effects for children’s cognitive abilities—in line with the effects of successful early childhood programs that focus on improving children’s specific skills and/or parenting behaviors—and simulated that more parents increase their education, beyond what current evaluations of two-generation programs have found. Because we also identified larger improvements for Black children in previous evaluations of two-generation programs, our simulations used effect sizes aligned with those improvements (e.g., positive stimulation improvements are larger for Black children, see Appendix A).

We used a national sample that includes families with an income below 200 percent of the federal poverty line to simulate a model in which states, schools, and communities implement accessible, high-quality two-generation programs for eligible young children and parents.

After changing child outcomes in the early years to represent the assumed effects of attending a high-quality two-generation program, we observed how those changes might affect outcomes at all subsequent life stages (see Figure 1) as the effects of the improved outcomes in early childhood ripple throughout the life course. We then compared these improvements to the baseline scenario in which no changes were made. Outcomes included measures of reading scores, math scores, behaviors, and health during the school years, as well as education, employment, and income in older stages. We also projected lifetime earnings through age 65, based on education and earnings at age 30. All outcomes are net of variables included in previous stages.

Figure 1. Visualization of the two-generation simulations in which improved outcomes in early childhood ripple throughout the life course

Related Research

- Preventing Births to Teens Is Associated With Long-term Health and Socioeconomic Benefits, According to Simulation

- Simulation Results Suggest That Improving School Readiness May Yield Long-term Education and Earnings Benefits

- Social Genome Model Early Childhood Version Technical Documentation and User’s Guide

NOTE: Measures in orange are changed as part of the simulation. Both simulations (aspirational and based on short-term impacts) change the same outcomes; only the magnitude of the simulated effects is different.

Findings

We find that two-generation programs can enhance children’s outcomes from preschool through adulthood, especially for Black children. As shown in Figure 1, changes early in a child’s life that affect children’s and parents’ outcomes as a result of the two-generation program ripple throughout the child’s life, having a positive and lasting effect on later outcomes. However, as children age, the effects of these programs may fade; with no subsequent “booster” programs at any other age, the magnitude of the initial effect may decline. The tables presented below show results for the aspirational simulation for a subset of selected outcomes. For ease of explanation, we focus largely on this simulation, which provides the larger impacts in most outcomes. While we discuss the simulation based on short-term impacts of programs in the text, we do not present tables.

Improvements in preschool to early adolescence

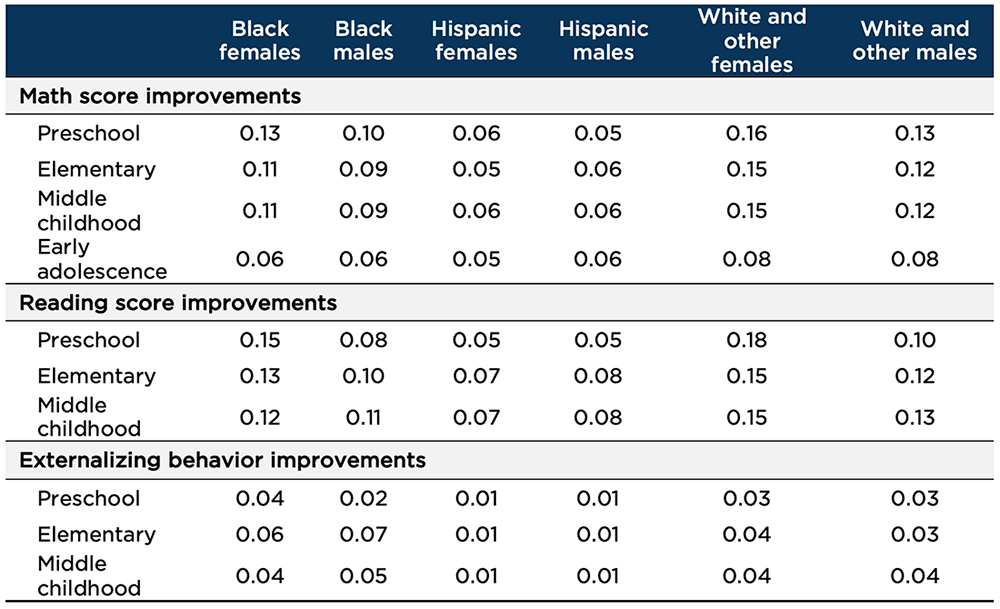

In our aspirational simulation, we found modest positive effects on outcomes; these improvements do not decline significantly as children age. Table 1 depicts students’ improved scores for some selected measures (math, reading, and externalizing behaviors scores) in each stage (preschool, elementary, middle school, and early adolescence) after the aspirational two-generation program is simulated. All improvements are measured in standardized deviations. We found modest effect sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.18 standard deviations, a size comparable to recent evaluations of educational programs for children. More importantly, unlike most educational interventions, these effect sizes do not decline significantly as children grow older and, in some cases, they are larger in the elementary and middle school stages than in preschool. In our simulation based on short-term impacts derived from research, we found the same pattern, although the impacts are smaller (between 0.01 and 0.07 standard deviations).

Our aspirational simulation also found some of the largest effects of two-generation programs for Black girls and boys. Black girls and boys see particularly large effects in reading scores, which are sustained until middle school. As noted previously, two-generation models have been able to achieve larger impacts for Black children in some outcomes, and those larger effects create larger improvements for Black children as the simulation proceeds through each life stage. We found the same pattern in our simulation based on short-term impacts derived from research, but with smaller improvements.

Table 1. Simulated improvements in selected preschool to early adolescence outcomes resulting from access to two-generation programs for children below 200 percent of the poverty line; aspirational simulation

Source: Social Genome Model.

Notes: N = 400,040. All outcomes are standardized and units are standard deviations. Improvements are the difference between the baseline values for each outcome (without the simulation) and the outcome after the simulation was performed. The White and other race group includes a small percentage of people who identify as Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander, or more than one race; because of sample size constraints, the SGM cannot estimate simulations separately for this group. Reading and externalizing behaviors scores are not available in Early Adolescence.

Improvements in adulthood

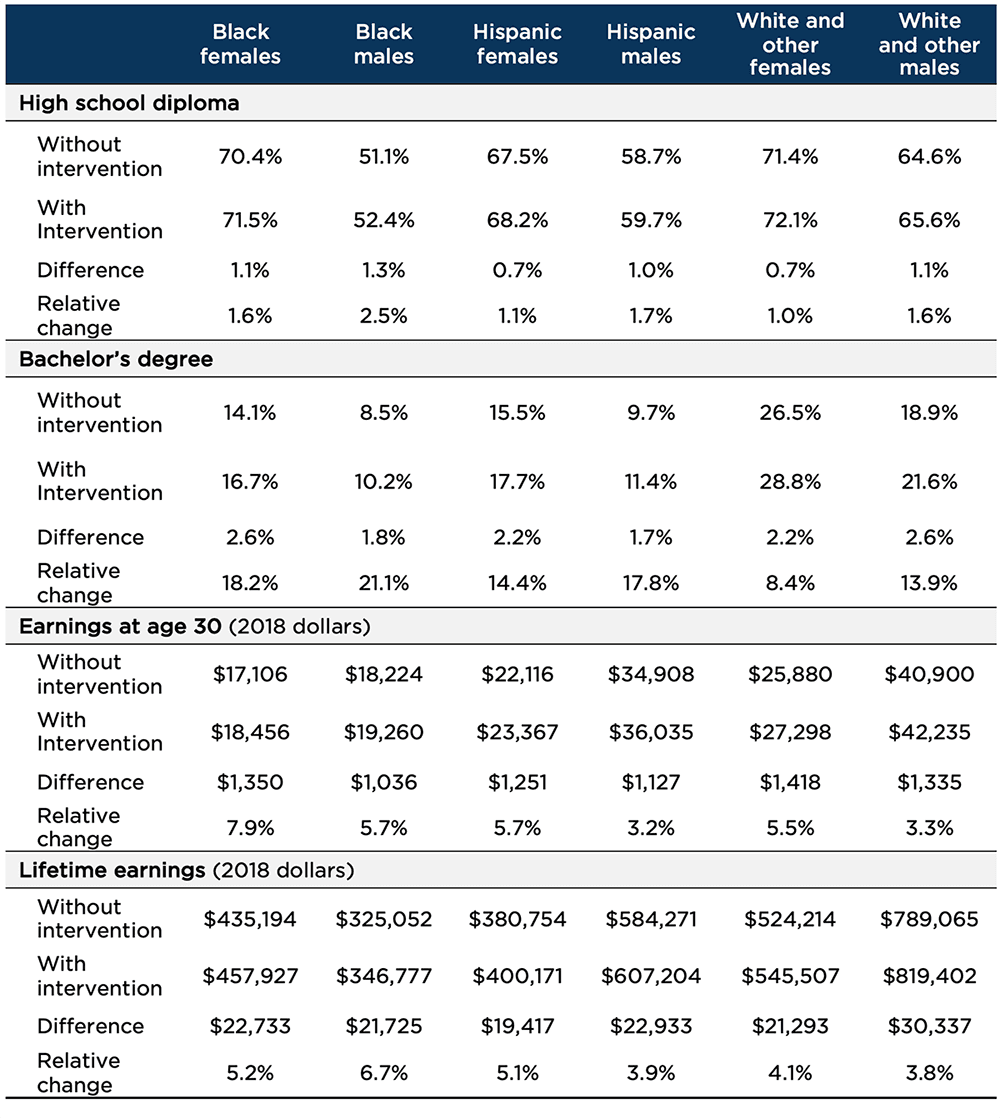

Our aspirational analysis found modest increases in high school graduation by age 19, with larger effects for Black children. Table 2 depicts students’ scores for each adulthood outcome measure in the absence of intervention (without intervention) and with intervention (with intervention), as well as the differences and relative changes. These modest increases reflect the likely reduction of effects over time, given that no booster programs are provided in the simulation. This effect could also reflect a limitation of the Social Genome Model itself, because there is some loss of continuity when ECLS-K cases are matched with NLSY97 cases to form the synthetic cohort (see Technical Appendix). The increases in high school graduation range from 0.7 to 1.3 percentage points. In our simulation based on short-term impacts, the increases are smaller—from 0.2 to 0.5 percentage points—with larger effects for Black children.

Educational increases in attainment of a bachelor’s degree by age 30 are also modest but notable, with increases of 1.7 to 2.6 percentage points in the aspirational simulation (Table 2). Given that fewer people of color (i.e., Black and Hispanic) have a bachelor’s degree at baseline (before the simulation), their improvements are larger in relative terms. For example, Black women would experience a 2.6 percentage-point increase (an 18.2% relative increase), a larger increase when compared to White men (also a 2.6 percentage-point increase, equivalent to a 13.9% relative increase). Again, the increases are smaller in our simulation based on short-term impacts—from 0.3 to 1 percentage points—with larger relative changes for Black men and women.

We found increases of up to 7.9 percent in earnings at age 30 and up to 6.7 percent in lifetime earnings in the aspirational simulation. Black men and women would experience the greatest relative increases in earnings at age 30 and throughout their lifetimes (Table 2). Nevertheless, absolute earnings increased by similar quantities (by about $1,300) for the highest-paid groups (White men and women) as for the lowest-paid groups (Black men and women). This indicates that, even if two-generation programs can help Black children overcome some systemic disadvantages, existing disparities in later life earnings would persist. In our simulation based on short-term impacts, the increases are again smaller: 0.8 percent to 3.1 percent change in earnings at age 30, and 1 percent to 2 percent for lifetime earnings.

Table 2. Simulated improvements in selected outcomes in adulthood resulting from access to two-generation programs for children below 200 percent of the poverty line; aspirational simulation

Source: Social Genome Model.

Notes: N = 400,040. The White and other race group includes a small percentage of people who identify as Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander, or more than one race; because of sample size constraints, the SGM cannot estimate simulations separately for this group.

Conclusions

The simulated long-term benefits of two-generation programs on children’s later outcomes suggest that these intervention approaches have the potential to enhance a range of outcomes for children in school, as well as their economic outcomes in adulthood. Our simulations found larger effects when we assumed that two-generation programs can have large impacts on children’s cognitive abilities and parents’ education—assumptions that, unfortunately, go beyond the current evidence of two-generation programs’ impacts. However, early childhood programs have been able to sustain large impacts in cognitive skills when they add skill-based curricula, especially around literacy and language skills. Additionally, a new wave of two-generation pilot programs seeks to further combine workforce training for parents with early childhood education programs for children using high-quality early childhood education centers as institutions that can coordinate services. The medium- and long-term impacts of these more recent programs are mostly unknown, and our simulations indicate that these new programs have the potential to significantly improve children’s lives—especially if they are able to increase children’s language skills and provide higher education opportunities for parents who are non-White.

Our simulations also found larger effects for Black boys and girls. Black children experienced the greatest relative growth in outcomes from preschool through high school, particularly in reading levels. These gains are sustained and do not completely fade as children age, and the gains translate into larger improvements for Black people in high school graduation, bachelor’s degree attainment, and earnings. However, prevailing disparities in earnings remain despite the larger improvements for Black people. More programs and policies are needed to address structural conditions that prevent racial groups from benefiting from equal opportunity in education and the labor market.

Limitations

As with all research based on microsimulations, this study has a number of limitations that users should consider when interpreting its findings. First, the Social Genome Model is not a causal model and cannot be used to make causal conclusions; therefore, all simulations should be considered as potential scenarios. Second, all regressions underlying the model are linear; the model does not account for any path that can lead to quadratic or cubic effects, or any nonlinear path. Third, the longitudinal data used are older by design in order to have data through age 30, and may not fully represent the characteristics of children and youth today. Finally, all the benefits are quantified for individuals and not for society.

Suggested citation

Piña, G., Moore, K.A., Sacks, V., & McClay, A. (2022). Two-generation programs may have long-term benefits, according to simulation. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/5444u5654p

Download Appendix

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube