Relative Foster Care Is Increasing Among American Indian and Alaska Native Children in Foster Care

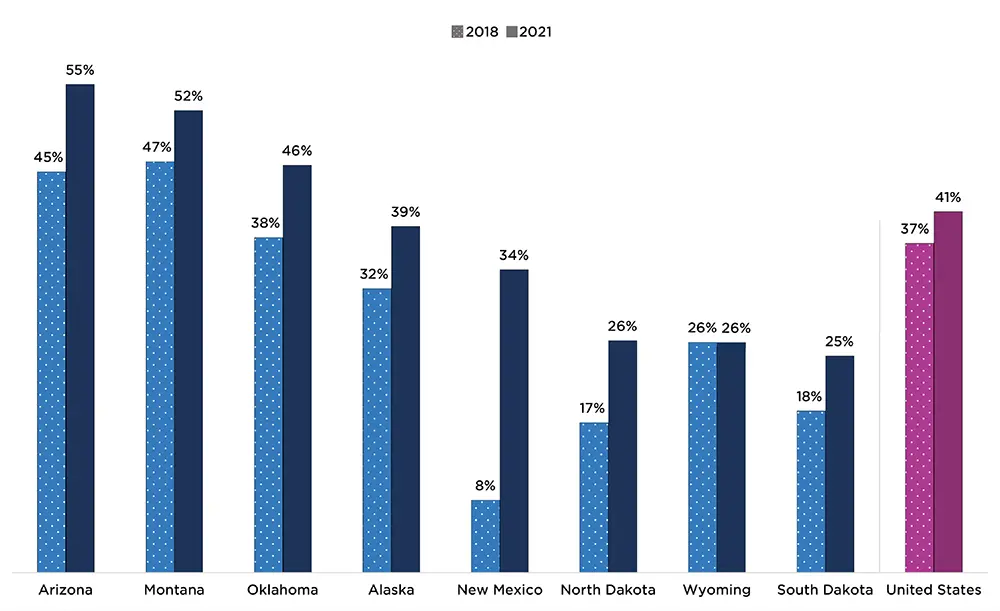

A new analysis from Child Trends finds that, from federal fiscal year (FFY) 2018 to FFY 2021, the use of relative foster care placements for American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children in foster care grew in seven of the eight states with the largest proportions of AIAN children.[1] Increases in the percent of AIAN children in foster care who were placed with a relative foster family were most pronounced in New Mexico, Arizona, and North Dakota (see figure below). This pattern mirrors what we have seen nationally for AIAN children in foster care, where the percent placed with relatives increased from 37 percent in FFY 2018 to 41 percent in FFY 2021. Recent increases in the use of relative foster care placements (a type of formal kinship care) reflect important shifts in child welfare policy and practice—such as the Family First Prevention Services Act—which prioritize preventing entry into foster care and support for kinship navigator services. The increased use of relative foster care placements for AIAN children in foster care also aligns with kinship caregiving values and preferences within many AIAN communities, and with the priorities of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which aims to maintain and sustain connections to family and culture.

Use of relative foster care placements for AIAN children in foster care is increasing in seven of the eight states with the largest proportions of AIAN children, and nationally

Percentages of AIAN children in foster care placed with a relative foster family in FFYs 2018 and 2021, for the 8 states with the largest proportion of AIAN children and nationally

Source and Notes

Kinship care is broadly defined as “the full-time care, nurturing, and protection of a child by relatives, members of their Tribe or clan, godparents, stepparents, or other adults who have a family relationship to a child.” Kinship care can be either informal or formal, depending on whether it involves supervision by a child welfare system. The data shown in the figure above reflect formal kinship caregiving of children in custody of a child welfare agency. Research finds that living with relatives is beneficial for children and youth when their parents are not able to be their primary caregivers. Compared to those placed with non-relatives, children who are placed with kin experience better academic, behavioral, and mental health outcomes and are more likely to stay with their siblings and maintain connections to family. For AIAN children, youth, and families, kinship care is important for the continued connection to community and culture that support strong attachment and bonding development.

The connections and relationships fostered by kinship care for AIAN children, youth, and families are promoted within the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). ICWA—federal legislation that affirms Tribal governments’ jurisdiction over the removal and placement in out-of-home care of AIAN children—promotes the use of kinship care by stating a preference for placement with a member of the child’s extended family. Recent challenges to the constitutionality of ICWA threatened to remove necessary protections for AIAN children and motivated several states to codify ICWA in their own laws. The Supreme Court has upheld ICWA as of 2023 but, by enshrining ICWA in state law, many AIAN children will remain protected in the event of further challenges to the federal law. Of the states in the figure above, four (Montana, Oklahoma, North Dakota, and Wyoming) have ICWA codified as state law and two (Arizona, South Dakota) have introduced legislation to this effect. New Mexico includes protections for American Indian children under its Indian Family Protection Act, signed into law in 2021.

It will take time to fully understand the impacts of recent federal and state shifts in child welfare policy and practice, including those relating to ICWA and the Family First Prevention Services Act. And policy keeps shifting: In Fall 2023, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced final regulations to remove barriers to licensure for kinship caregivers and ensure that kinship foster homes receive the same financial support as non-kinship foster homes. These policy changes have the potential to increase equity and security for kinship caregivers. In the meantime, increases in relative foster care placements for AIAN children are a positive indicator of change. Continued attention toward supporting the needs of families interested in or already providing kinship care through innovative, research- and practice-informed strategies will help ensure equity for relative foster families and maximize the full benefits of kinship care to AIAN children.

Footnote

[1] The states with the largest proportions of AIAN children and young people from birth to age 20 were determined using 2021 population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010-2020/state/asrh/

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Child Trends staff members for their reviews and feedback on this datapoint (Jody Franklin, MPP, MA; Brent Franklin, MPP; Dominique N. Martinez; and Kristen Harper, EdM).

Suggested citation

Around Him, D., Williams, S.C., Martinez, V., and Jake, L. (2023). Relative foster care is increasing among American Indian and Alaska Native children in foster care. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/4808o7175w

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube