American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) Children Are Overrepresented in Foster Care in States With the Largest Proportions of AIAN Children

Author

Note: We updated this blog on April 26, 2023 to correct an error in the percentage of AIAN children in the overall child population; the error was the result of a cut/paste mistake in sorting our data. The figure now shows a corrected value for the United States (% of child population that is AIAN updated from 3% to 1%) and includes only the eight states with a proportion of AIAN children greater than 1 percent of the total child population (Minnesota, Oregon, and Nebraska were removed, and Wyoming was added). Additionally, the opening paragraph now refers to these eight states rather than the original 10.

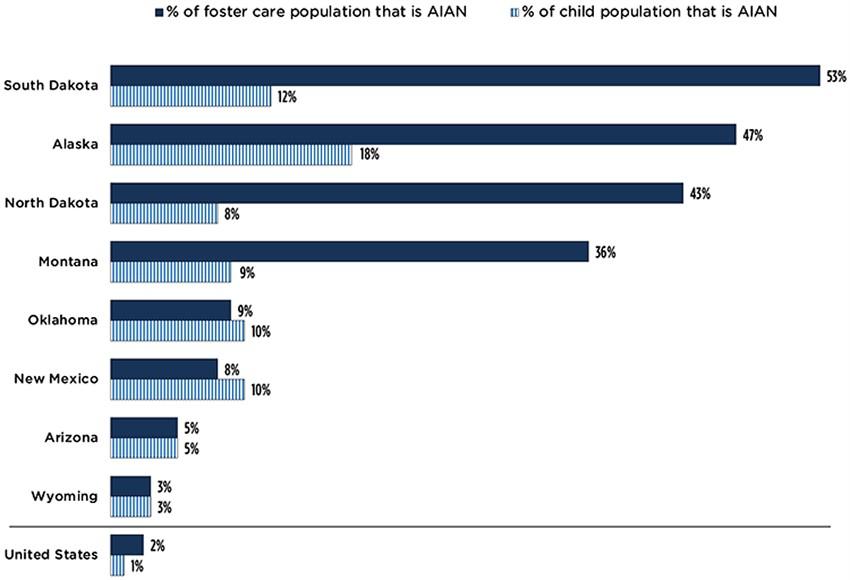

In the eight states with the largest proportions of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children (AIAN child population greater than 1% of the state’s total child population),[1] AIAN children are overrepresented in foster care in nearly every state when comparing their percentages in the foster care and total child populations (see figure below). Of these eight states, the percentage of AIAN children in foster care was highest in South Dakota, Alaska, North Dakota, and Montana; and lowest in Arizona and Wyoming. These findings are derived from federal fiscal year 2020 data.

Figure: AIAN children are disproportionately represented in foster care in the top 4 states with the largest proportions of AIAN children

Percentages of AIAN children among the foster care and child populations, for the 8 states with the largest proportion of AIAN children

Source: Williams, S. C. (2022). State-level data for understanding child welfare in the United States. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/state-level-data-for-understanding-child-welfare-in-the-united-states

Foster care placement occurs when a child protective services worker and a court determine that it is not safe for a child to remain at home. Children in foster care need strong support systems because removal from the home can be traumatic: Their routines are disrupted, and they become separated from familiar people and places. AIAN children placed in foster care may also be separated from their Indigenous communities and cultures, which provide access to preventive and protective values and practices.

There is a long history of racial disproportionality and disparities at every stage of child welfare system involvement, especially for AIAN and Black children. Behind the numbers shown in the figure above, AIAN children have faced a history of forced and coercive removal from their homes and communities into government and missionary boarding schools. These assimilation practices, facilitated by federal policies as far back as the 1800s, resulted in historical trauma that has significantly impacted the well-being of generations of Indigenous individuals, families, and communities.

Researchers, policymakers, and practitioners can enhance existing efforts to reform the child welfare system with strategies that aim to address—across multiple levels—child welfare injustices that are specific to Indigenous children, families, and communities. These strategies include:

- Prioritize placements among extended family and others in Tribal communities for children who cannot remain safely at home. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) provides a legal foundation for this approach, and many Tribal Nations and organizations, policy officials, child welfare and adoption agencies, and medical professionals support ICWA and its provisions. Federal court cases that question the constitutionality of ICWA, such as Haaland v. Brackeen, jeopardize the sovereign right of Tribal Nations to protect AIAN children and risk perpetuation of assimilation practices that have harmed AIAN children in the past.

- Equip child welfare and other family-serving systems to understand and support Indigenous children and families specifically. Family-serving agencies can rely on resources like the National Indian Child Welfare Association’s (NICWA) toolkit—American Indian & Alaska Native Grandfamilies: Helping Children Thrive through Connection to Family and Cultural Identity—to improve their understanding of the impacts of separating Indigenous children from their families, as well as opportunities to provide culturally appropriate services. Caseworkers and child welfare agency leaders can also benefit from the federal Children’s Bureau’s Capacity Building Center for Tribes, which includes a wealth of resources and trainings designed to improve child welfare practice for Tribal Nations and Indigenous children and families.

- Support Indigenous families with culturally based and informed prevention and early intervention services. For example, Tribal communities have used NICWA’s Positive Indian Parenting curriculum for decades to share traditional parenting practices and introduce ways for families to apply traditional lessons in today’s society. The Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health’s evidence-based home visiting model, Family Spirit, also promotes family well-being and was recently rated as a promising in-home parent skill-based program in the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse.

Endnote

[1] Data for the AIAN child population under age 18 in 2020 are from the U. S. Census Bureau and are publicly available from the Kids Count Data Center.

The author would like to thank Elizabeth Jordan, Sarah Catherine Williams, Astha Patel, Valerie Martinez, and the Child Trends communications team for their reviews of and contributions to this piece.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube