Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Preschoolers’ Experiences

A preschool child who is healthy and ready to learn demonstrates the ability to regulate their behavior and emotions, key social and emotional competencies, motor skills, health, and early learning skills.[1] Because healthy development across these domains is more challenging for some children than for others, it is valuable to understand which experiences during the preschool years are associated with children’s health and readiness for school. The analyses in this brief examine the associations between a young child’s experiences and the extent to which parents report that the child is healthy and ready to learn. Data used for these analyses are from the 2017 and 2018 waves of the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) for children ages 3 to 5, and are nationally representative of children in this age range.

Key findings

Several key factors are consistently related to how healthy and ready to learn a preschool child is found to be.

- Children’s experiences and routines are associated with being healthy and ready to learn. Children’s experiences—including their experiences in the home—are consistently associated with their likelihood of being healthy and ready to learn. For instance, children whose parents report that their children receive fewer than two hours of screen time daily, and that their children receive the recommended amount of sleep, are more healthy and ready to learn than children whose parents report two or more hours of screen time or that their children receive less than the recommended amount of sleep.

- Adverse experiences and health conditions relate to being healthy and ready to learn, as expected. Children’s early life experiences and health conditions can also present developmental hazards; findings indicate that the presence of a special health care need (particularly one with functional limitations), and an accumulation of adverse childhood experiences (such as experiencing or witnessing violence), are associated with lower rates of being healthy and ready to learn.

- Individuals, systems, and policies play a role in children’s health and readiness for school. Such individuals and systems include parents, caregivers, medical and mental health providers, the health care system, and the policies that govern health care access.

About the survey and measure

Parents or caregivers who participated in the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) respond to a set of items about their child’s development. From these responses, measures of each child’s health and readiness to learn were developed for four domains: self-regulation, health, early learning, and social emotional competencies. Specifically, with respect to their development, HRSA’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA MCHB) with Child Trends identified children as “On Track,” “Emerging,” or “Needs Support” in each of the four domains. In addition, an overall summary National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn (HRTL) was defined according to whether children were healthy and ready to learn in all four domains, in three domains, two domains, or in zero or one domain. This brief uses the metric of On Track in all four domains as representative of being “Healthy and Ready to Learn.”

Analyses assess a range of child experiences related to being On Track in all four domains of the HRTL measure.* These experiences, which arents report on in the NSCH, include frequency of book reading, amount of screen time, amount of sleep, presence of a special health care need, access to family-centered care in a medical home, and exposure to adverse childhood experiences (see Appendix B for more information on each experience). Associations or differences described in this brief reflect statistically significant differences as indicated by a p-value < .05. Furthermore, we used multivariate analyses to repeat the primary analyses of interest controlling for social, economic, and demographic factors, including child race and ethnicity, sex, parental education, family structure, and family income. The findings from the multivariate analyses help to distinguish the association of each child experience with a HRTL score from other known influences on child development. We present the findings from multivariate descriptive analyses in the text; please contact the authors for detailed tables of findings.

Further detail on the HRTL measure can be found in Appendix A. Details on each child experience that parents reported on, including the wording of items and response options in the HRTL measure, are available in Appendix B. Findings for each of the measure’s four domains are presented in Appendix C. Related briefs with additional analyses of the association between the HRTL measure and other family, neighborhood, and demographic characteristics are available from Child Trends.**

* Details on each covariate including item wording and response options are available in Appendix B.

** The demographic characteristics include parents’ education, family structure, family income, food security, household primary language, access to health insurance, children’s race/ethnicity, children’s sex, and children’s age. The family and neighborhood characteristics include family strengths, family routines, parent physical and mental/emotional health, parenting difficulties, the parent’s emotional support for parenting, neighborhood amenities and challenges, and neighborhood supports for childrearing.

The Healthy and Ready to Learn National Outcome Measure

The pilot Healthy and Ready to Learn Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant National Outcome Measure (NOM) was developed by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA MCHB), in collaboration with Child Trends. The measure uses data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), a nationally representative, annual household survey funded and directed by HRSA MCHB, and designed to be completed by parents of children ages 0 to 17; Healthy and Ready to Learn questions are specific to children ages 3 to 5. It is a whole-child assessment that covers four domains of development: early learning skills, social-emotional development, self-regulation skills, and physical health and motor development. For more information on the development of the measure, please visit the HRTL description and FAQ page and Appendix A.

Findings

Download

Preschool children whose family members read, sing, and/or tell stories to them most days of the week are much more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than children in families that engage in these activities less frequently; this finding holds true even when accounting for other socio-demographic characteristics.

Activities that involve reading books, singing songs, and telling stories are critical early learning experiences for young children, and engagement in these activities is a potent predictor of young children’s pre-academic and social skills.[2] In the NSCH, parents report on how frequently their child engaged in these activities weekly (see Appendix B for items and coding), and these frequencies were linked to scores on HRTL.

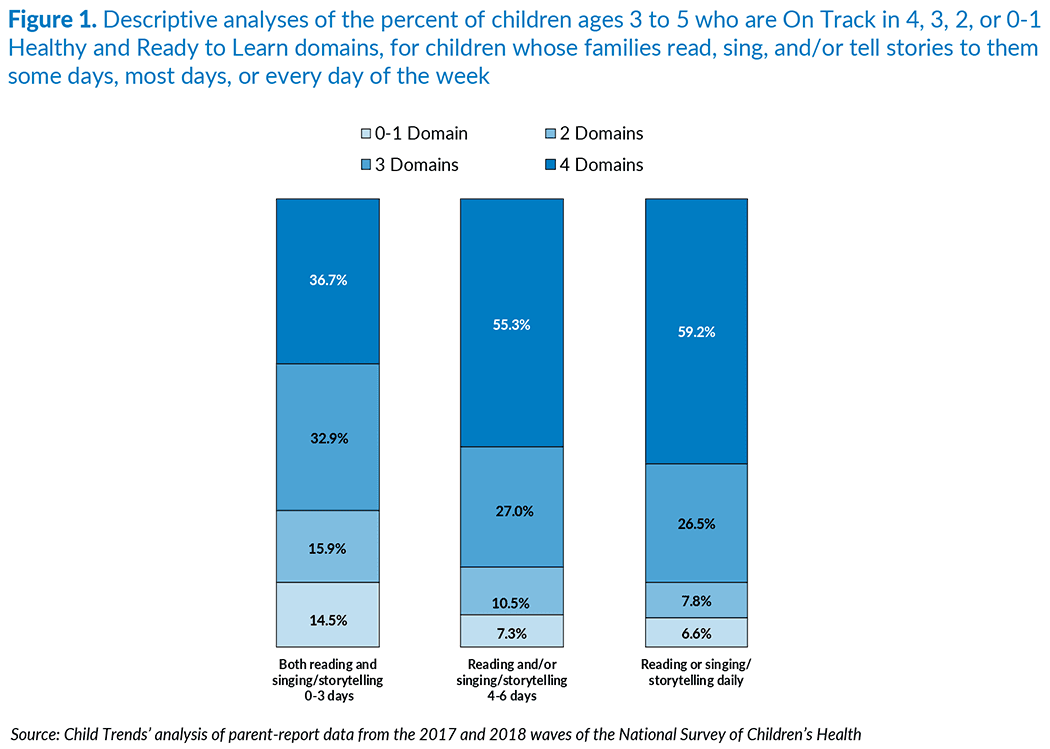

Approximately 30 percent of families reported reading, singing, or storytelling 0 to 3 days per week, 34 percent reported engaging in these activities 4 to 6 days a week, and 36 percent reported engaging in them daily. As Figure 1 shows, children in families that reported engaging in reading, singing, or storytelling three or fewer days a week are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn, and more likely to be On Track in zero to one or two domains, when compared with children in families that engage in these activities more often. Specifically, 37 percent of children in families that engage infrequently in these activities are healthy and ready to learn, compared with 55 and 59 percent of families who engage in these activities most days or every day, respectively.

Separate descriptive analyses of the four HRTL domains, presented in Appendix C, indicate that children in families that engage in reading, singing and/or storytelling most days or every day of the week are more likely to be On Track in three of the four individual HRTL domains, including early learning, social-emotional, and self-regulation, but not health. Furthermore, findings linking reading, singing, and/or storytelling to being healthy and ready to learn remained statistically significant even in analyses that controlled for selected family and social characteristics.

Related Content

- Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Family and Neighborhood Characteristics for Preschoolers

- Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Socioeconomic Conditions for Preschoolers

- Being Healthy and Ready to Learn is Linked with Preschoolers’ Experiences

- Comparing the National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn with Other Well-Being and School Readiness Measures

- A promising new measure of kindergarten readiness

- National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn

Preschool children whose parent reports exposure to a high amount of screen time per day are considerably less likely to be healthy and ready to learn than their peers exposed to moderate or low amounts of screen time, even when accounting for other socio-demographic characteristics.

Screen time is a topic of concern for both parents and pediatricians; research suggests that screen time, particularly when it exceeds the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation of one hour per day,[3] can negatively affect children’s physical, cognitive, language, and social-emotional development.[4], [5] Screen time is assessed in the NSCH by two items that ask parents or caregivers to report 1) the total number of hours children spend with a TV on an average day, and 2) the total number of hours children spend with a computer, phone, or gaming device or computer on the average day. We combined the hours reported for the two items and created three categories of screen time: less than or equal to one hour combined; 2 hours combined; and more than 2 hours combined.

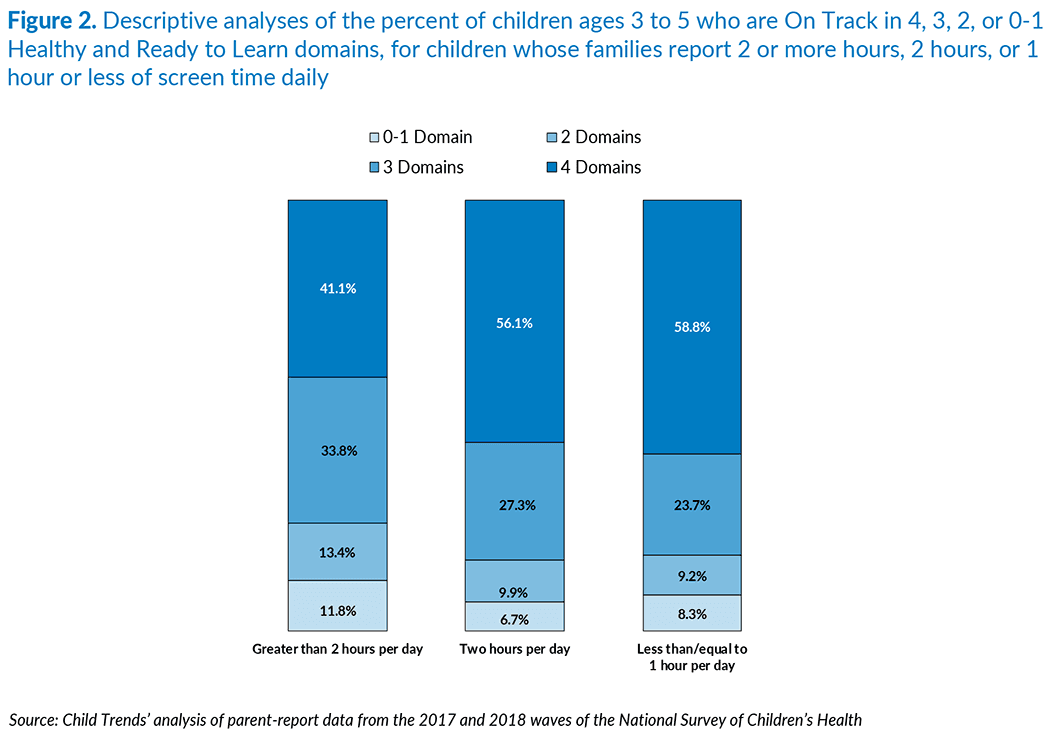

Approximately 37 percent of parents reported that their children have two or more hours of screen time per day, 30 percent reported two hours, and 33 percent reported one hour or less per day. As shown in Figure 2, children’s status on the HRTL measure is strongly associated with parents’ reports of screen time. Specifically, 41 percent of children whose parents reported two or more hours of screen time a day are healthy and ready to learn, compared with 56 and 59 percent of children whose parent indicated less screen time.

Detailed descriptive analyses for the four individual HRTL domains, reported in Appendix C, indicate similar patterns; however, the largest differences are in the self-regulation domain, for which only 60 percent of children exposed to more than two hours of screen time a day are On Track compared to 71 and 76 percent of children exposed to two hours, or to one hour or less of screen time daily, respectively. In addition, analyses controlling for social, economic, and demographic characteristics found that children whose parents reported two or more hours of screen time per day are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn compared to children whose parents reported two or fewer hours of screen time.

Preschool children whose parents report that their child sleeps ten or more hours per night are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than children whose parents report less sleep time, even when accounting for socio-demographic characteristics.

Sleep quality and duration is an important predictor of overall health in young children and across the lifespan.[6] An item in the NSCH asks parents about the average number of hours their child sleeps per day, including overnight and naps. Given the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s guidance of 10 to 13 hours of sleep per day for this age group,[7] we created two categories: children who sleep, on average, nine hours or less and children who sleep 10 or more hours.

To receive the latest updates on the Kindergarten Readiness National Outcome Measure, sign up for our newsletter.

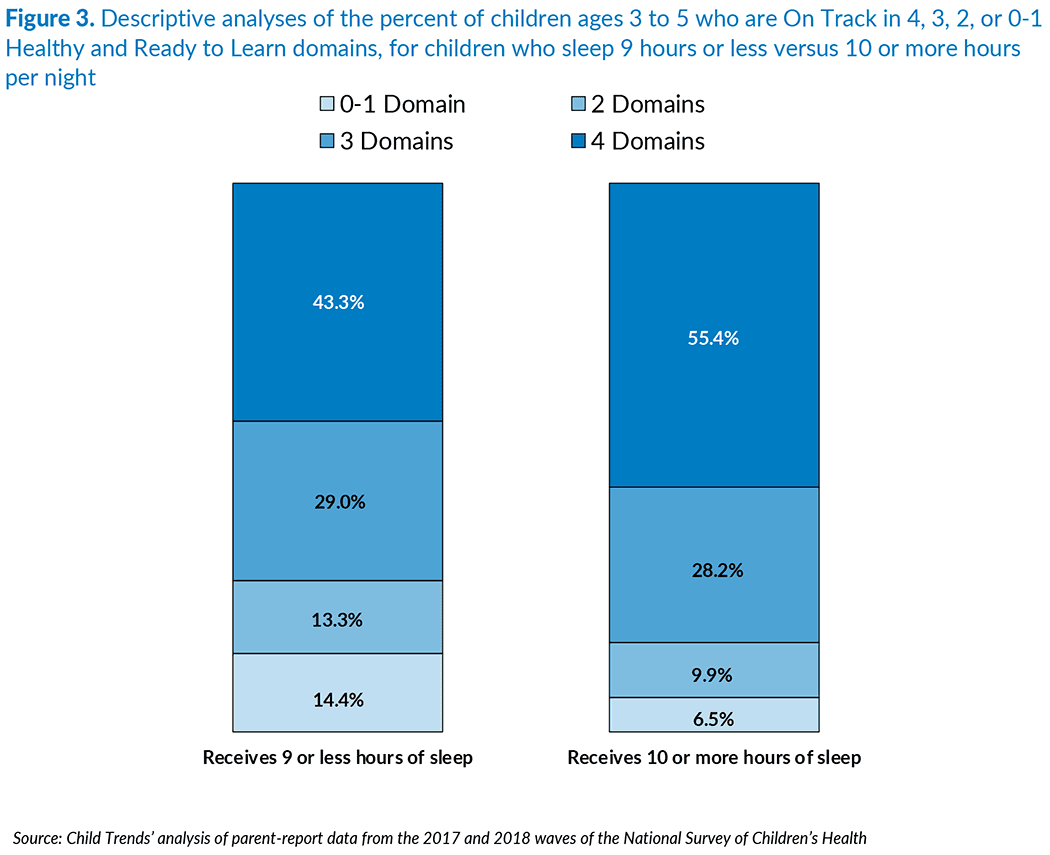

Approximately two-thirds of parents reported that their child sleeps 10 or more hours a day (64 percent). As shown in Figure 3, there are clear differences in rates of being healthy and ready to learn between children who sleep nine hours or less versus children who sleep 10 or more hours daily. When compared to children getting 10 or more hours of sleep per day, a smaller percentage of children sleeping nine hours or less are On Track in all four domains (43 versus 55 percent).

Analyses by the individual HRTL domains mirror these findings; in each domain, children whose parents reported that their child receives nine hours of sleep or less per day are less likely to be rated On Track (see Appendix C). Findings were robust even when social, economic, and demographic characteristics were added to the model as controls; sleeping 10 or more hours per day was associated with a greater likelihood of being healthy and ready to learn compared to sleeping fewer hours.

Preschool children with special health care needs are On Track in fewer domains than children without special health care needs, even when accounting for other socio-demographic characteristics.

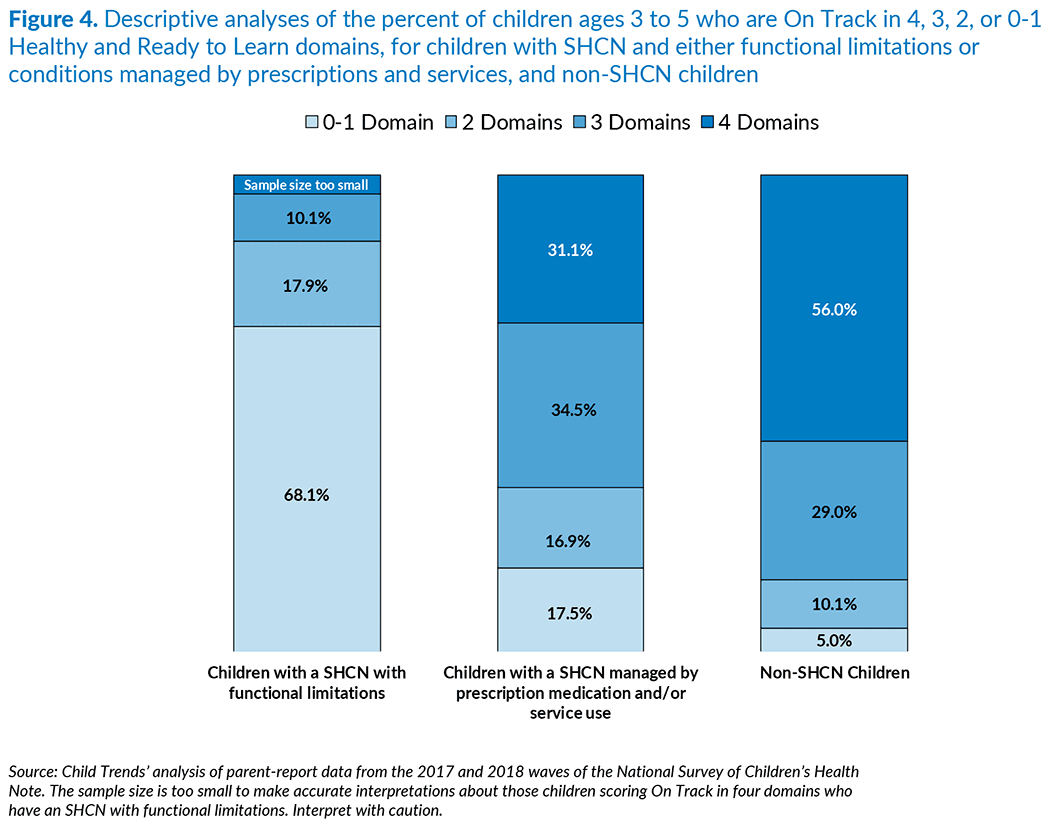

Children with special health care needs (CSHCN) are those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children, generally.[8] Children identified as having functional limitations are limited in their ability to do what their peers do, and these limitations may affect one or more domains of their development.[9] Thus, we would expect that children whose parent reports an SHCN, particularly those children with a functional limitation, are less likely to be On Track to be healthy and ready to learn compared with their peers without an SHCN. The NSCH contains the Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) Screener© to support the collection of detailed national and state-level estimates of the prevalence and impact of special health care needs among children from birth to age 17 and their families. As part of the screener, parents or caregivers report whether their child experiences one or more of five health consequences or impacts as a result of a medical, behavioral, or other health condition that has lasted (or is expected to last for) 12 months or longer. For these analyses, responses across five questions were collapsed into three categories, shown in Figure 4 (for more information, see Appendix B).

Children without special health care needs (non-SHCN) comprised the majority of the sample (87 percent), while 9 percent of children were reported to have an SHCN managed by prescription or service use, and 4 percent of children were reported to have an SHCN with a functional limitation. As expected, the majority of children who have an SHCN with a functional limitation are On Track in zero or only one domain (68 percent). By comparison, 17 percent of children who have an SHCN with conditions managed by prescriptions or services and 5 percent of non-SHCN children are On Track in zero or only one domain. Only 31 percent of children who have an SHCN with conditions that are managed by prescriptions or service use were reported as healthy and ready to learn, as compared with 56 percent of non-SHCN children. These findings serve as confirmation that the HRTL measure is differentiating by health status as expected.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that the gaps between each SHCN group and non-SHCN group are large in each individual domain (see Appendix C), not just on the overall HRTL measure. Analyses controlling for other social, economic, and demographic characteristics also corroborated findings that CSHCN with functional limitations were the least likely to be healthy and ready to learn, and non-SHCN children were more likely to be healthy and ready to learn than CSHCN overall.

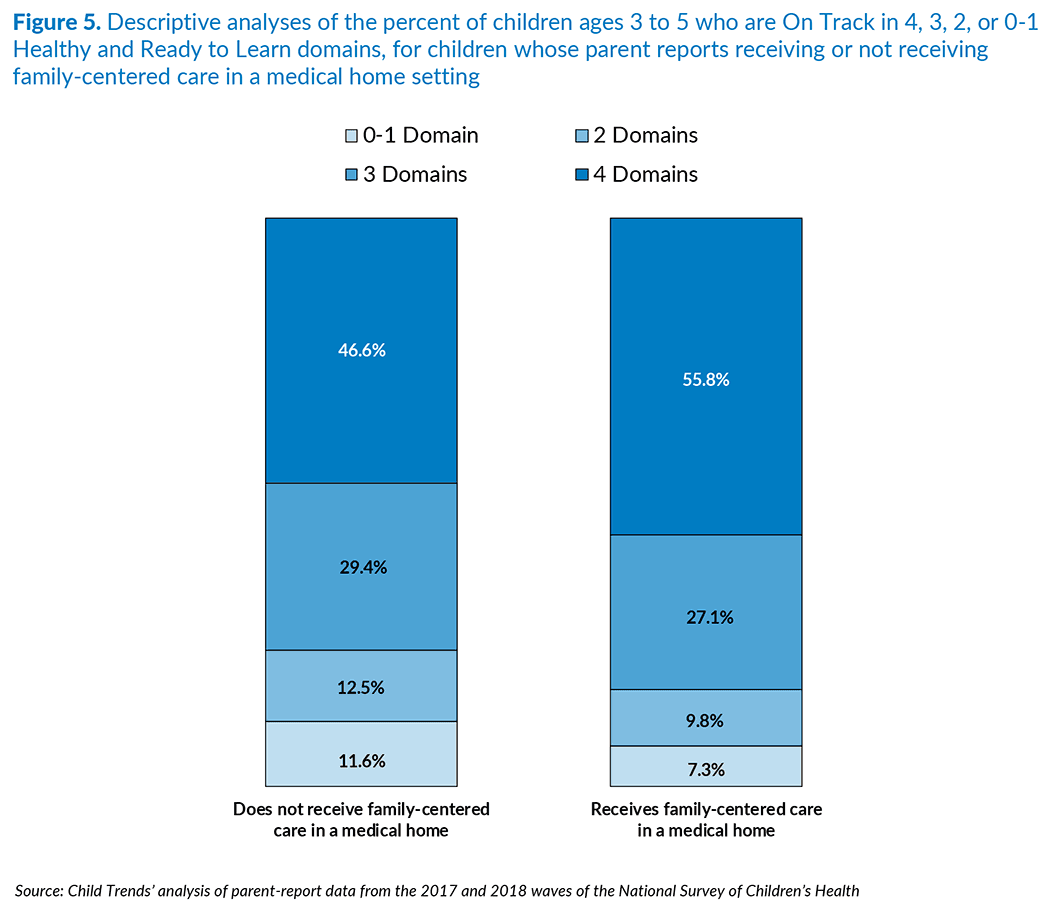

Preschool children are more likely to be healthy and ready to learn when they receive family-centered health care in a medical home, although this association is not statistically significant once socio-demographic differences are accounted for.

A robust body of research indicates that families with access to a medical home that provides family-centered care can reap a range of benefits for children, including reduced obesity and better outcomes for children identified with developmental delays and social-emotional and behavioral issues.[10], [11], [12] The NSCH asks all parents and caregivers to report on 15 items related to their child’s medical care; specifically, parents report on whether their child receives medical care in a medical home (i.e., care from a usual, consistent care provider), and on the quality of that care (i.e., quality of care coordination, referral, and communication with provider). Responses across these 15 items were collapsed into two categories based on whether the child receives family-centered medical care in a medical home.

Approximately half of children fell into each category, with 55 percent of parents reporting that their child receives family-centered care in a medical home, and 45 percent reporting that their child does not receive this type of care. As Figure 5 shows, there was a positive relationship between reports of children receiving family-centered care in a medical home and children’s readiness for school. Specifically, among those who receive family-centered care in a medical home, 56 percent of children were On Track in all four HRTL domains, as compared to 47 percent of children who do not receive this type of care. However, in analyses controlling for social, economic, and demographic characteristics, the association between family-centered care in a medical home and being healthy and ready to learn fell short of statistical significance, meaning that no meaningful differences were found between the receiving and not-receiving groups. This finding suggests that access to family-centered care in a medical home may be strongly related to family economic status.

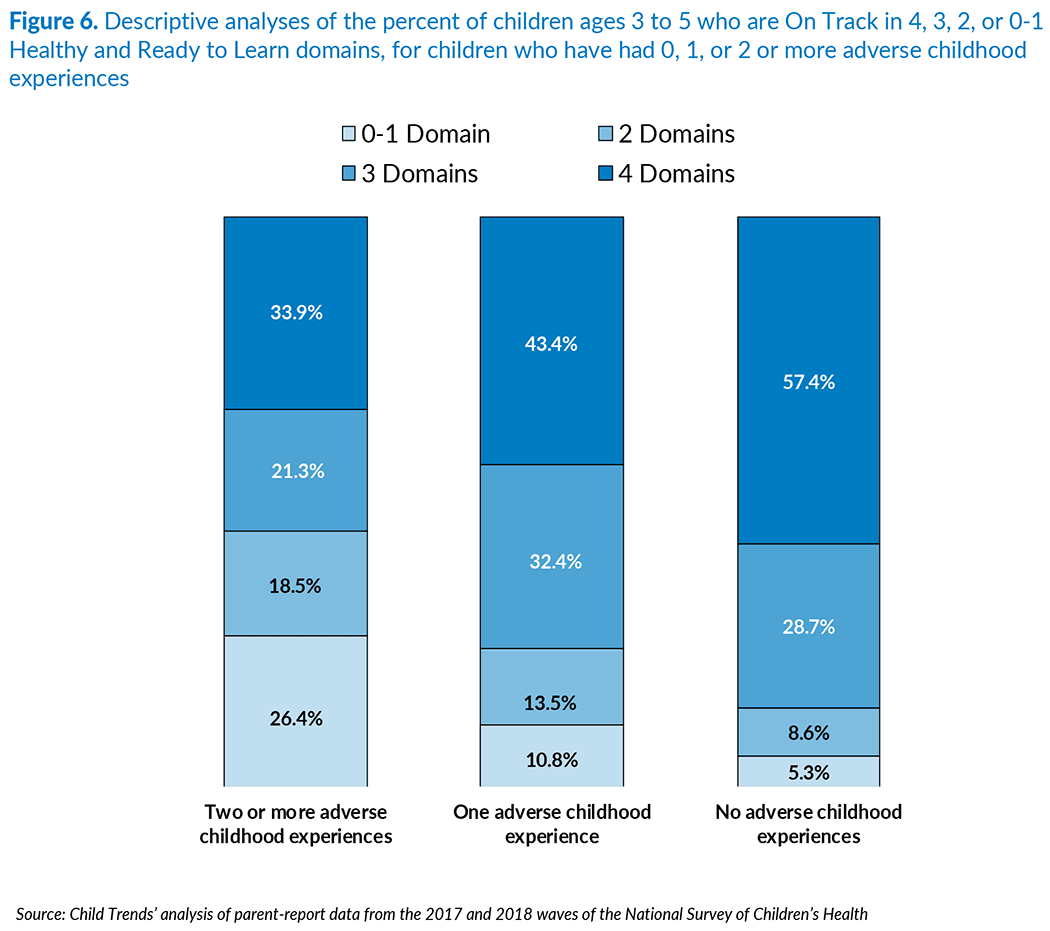

Preschool children’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences is strongly related to their health and readiness to learn, even when accounting for other socio-demographic characteristics.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as experiencing or witnessing violence, are consistently linked with negative short- and long-term effects on health, learning, and well-being.[13] ACEs are especially harmful when they are experienced in the absence of protective factors, such as supportive child care environments with teachers trained in trauma-informed approaches, supportive parenting and parenting supported by professionals, and consistent household routines.[14], [15] The NSCH asks the parent or caregiver to report whether the child has experienced any of 8 ACEs. For these analyses, we summed the number of reported experiences and created three categories: no experiences, one experience, and two or more experiences, as shown in Figure 6.

As shown in Figure 6, a clear, stepwise pattern of findings from these data indicates that as children are reported to have encountered more ACEs, they are less likely to be On Track for health and school readiness. While over half of children with no ACEs are On Track across all four domains (57 percent), fewer than half of those with one ACE (43 percent) and approximately one-third of those with two or more ACEs (34 percent) are On Track across all four domains.

Detailed descriptive analyses indicate that this pattern persists for each individual HRTL domain, with gaps of at least 10 percentage points between those who experienced two or more ACEs and those who experienced one, and gaps of at least 6 percentage points between those who experienced one and those who experienced none (see Appendix C). In addition, when social, economic, and demographic characteristics are included in the model, exposure to adverse experiences is still associated with children’s health and readiness to learn; those with one ACE are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn compared to those with none, and those with two or more ACEs are less likely to be healthy and ready to learn compared to those with one or none.

Discussion

The National Survey of Children’s Health includes many important parent-report indicators of children’s well-being. Taken together, these indicators can help researchers and policymakers understand the experiences of young children in the United States, and how they are related to children’s health, school readiness, and their well-being outcomes. This brief considers how childhood experiences—such as book reading, screen time, sleep, and family-centered medical care—are associated with the health and school readiness of children ages 3 to 5 as assessed in the HRTL measure.

Children who receive more supportive and stimulating care, who sleep more, and who have not had ACEs are consistently more likely to be On Track for being healthy and ready to learn, based on the parent-report measures embedded within the NSCH. These findings are consistent with the child development literature. For example, the importance of book reading and sleep have been well-documented across many studies.[16] Screen time is an emerging research topic, with evidence growing that more than two to four hours of screen time a day can have negative effects on children;[17] our findings correspond with the current small body of research on screen time. In addition, our analyses that account for the influence of social, economic, and demographic characteristics, such as child race, parent education, and family income, find that each child experience (i.e., reading/singing/storytelling, screen time, sleep, and ACEs) remains associated with being healthy and ready to learn. These findings suggest that each of these child experiences is relevant to children’s health and readiness for school, above and beyond other known influences on development.

In accordance with the research literature, the findings from this brief suggest that many aspects of children’s lives are associated with their ability to self-regulate, engage positively with peers, learn new concepts, and develop healthfully. As an example of findings from this brief, serious risks to children, such as ACEs, are strongly related to their health and readiness to learn. Many risks to healthy development can be prevented or successfully mitigated through parental education regarding topics such as screen time, sleep, and reading. Other risks can be prevented or mitigated through policies to improve health care access and quality, which includes providing family-centered care as well as preventing ACEs and treating those who are affected by these experiences.

It is not surprising that the presence of a special health care need is associated with reduced health and readiness across domains; parents of preschoolers who have a special health care need with a limitation report lower levels of health and development for their child than do parents of children without special health care needs. Thus, this characteristic serves as an important checkpoint for the HRTL measure; that is, we would expect that children whose parents reported such limitations in one part of the survey would also have reduced skills as assessed by the HRTL items. It is not the case, however, that a child with special health care needs cannot succeed in school, and this factor is not necessarily the same as the other risk factors examined in this brief, such as screen time, ACEs, or even family-centered medical care in a medical home—each of which is more pliable or readily addressed. Rather, children with special health care needs, particularly those with functional limitations, require access to individualized learning plans and high-quality specialized health care to develop to their full potential.

Taken together, the findings in this brief suggest that children’s early experiences and routines are related to parent reports of children’s health and readiness for school. Furthermore, the association between these experiences and being healthy and ready to learn persists whether it is examined by individual domain or across all four domains, suggesting that the domains of development are interconnected. In other words, these experiences do not have specific, narrow associations with particular sets of skills; rather, the relationship between these experiences and child development is broad.

We recognize that the associations described here are correlational and that no causal conclusions can be drawn. Furthermore, we note that the National Outcome Measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn examined here is a pilot measure that is likely to be strengthened in the coming years. Nonetheless, the kinds of associations discussed in this brief have also been found in analyses of the 2016 NSCH, using a HRTL measure that is slightly different in terms of the measure’s items and coding of items in the measure. These patterns, therefore, appear to be very consistent. HRTL data will be available for each state and will be made available on an annual basis, as a part of the National Survey of Children’s Health.

Conclusion

The analyses presented in this brief indicate that preschool children’s experiences are consistently and strongly associated with the extent to which they are healthy and ready to learn. Findings suggest that many environments and systems that influence children’s experiences—such as the home, the medical care setting, and the medical care system—are associated with children’s health and readiness.

The HRTL measure is an important new indicator of child well-being that allows researchers and policymakers to track trends in health and readiness for school—along with these trends’ links to childhood adversity year over year—through the National Survey of Children’s Health. In addition, NSCH data are available for each state. Given that the HRTL measure is in its pilot phase, it is possible that the exact proportions of children assessed as healthy and ready to learn may change as the measure is improved in future iterations. Nevertheless, the associations presented in this brief align with the findings of numerous research studies and suggest that, if policymakers want to improve young children’s school readiness, they need to support families and address early childhood adversity.

Download

References

[1] Ghandour, R. M., Moore, K. A., Murphy, K., Bethell, C., Jones, J. R., Harwood, R., … & Lu, M. (2019). School readiness among US children: Development of a pilot measure. Child Indicators Research, 12(4), 1389-1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9586-8

[2] Muñiz, E. I., Silver, E. J., & Stein, R. E. (2014). Family routines and social-emotional school readiness among preschool-age children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(2), 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000021

[3] Council on Communications and Media. (2016). Media and young minds. Pediatrics, 138(5), e20162591. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2591

[4] Domingues‐Montanari, S. (2017). Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 53(4), 333-338. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13462

[5] Ribner, A., Fitzpatrick, C., & Blair, C. (2017). Family socioeconomic status moderates associations between television viewing and school readiness skills. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 38(3), 233-239. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000425

[6] Paruthi, S., Brooks, L. J., D’Ambrosio, C., Hall, W. A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R. M., . . . Wise, M. S. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785–786. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866

[7] Paruthi, S., Brooks, L. J., D’Ambrosio, C., Hall, W. A., Kotagal, S., Lloyd, R. M., . . . Wise, M. S. (2016). Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785–786. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866

[8] Read D., Stein R. E. K. , Blumberg S. J., Wells N., & Newacheck P. W. (2002). Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 2, 38-47. https://doi.org/10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2

[9] O’Connor, M., Howell‐Meurs, S., Kvalsvig, A., & Goldfeld, S. (2015). Understanding the impact of special health care needs on early school functioning: Z conceptual model. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(1), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12164

[10] Duby, J. C. (2007). Role of the medical home in family-centered early intervention services. Pediatrics, 120(5), 1153-1158. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2638

[11] Toomey, S. L., Chan, E., Ratner, J. A., & Schuster, M. A. (2011). The patient-centered medical home, practice patterns, and functional outcomes for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Academic Pediatrics, 11(6), 500-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2011.08.010

[12] Barkin, S. L., Gesell, S. B., Po’e, E. K., Escarfuller, J., & Tempesti, T. (2012). Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American preschool-aged children. Pediatrics, 130(3), 445-456. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3762

[13] Giovanelli, A., Reynolds, A. J., Mondi, C. F., & Ou, S. R. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and adult well-being in a low-income, urban cohort. Pediatrics, 137(4), e20154016. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4016

[14] Sciaraffa, M. A., Zeanah, P. D., & Zeanah, C. H. (2018). Understanding and promoting resilience in the context of adverse childhood experiences. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(3), 343-353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0869-3

[15] Traub, F., & Boynton-Jarrett, R. (2017). Modifiable resilience factors to childhood adversity for clinical pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 139(5), e20162569. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2569

[16] Forget‐Dubois, N., Dionne, G., Lemelin, J. P., Pérusse, D., Tremblay, R. E., & Boivin, M. (2009). Early child language mediates the relation between home environment and school readiness. Child Development, 80(3), 736-749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01294.x

[17] Lin, L. Y., Cherng, R. J., Chen, Y. J., Chen, Y. J., & Yang, H. M. (2015). Effects of television exposure on developmental skills among young children. Infant Behavior and Development, 38, 20-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.12.005

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube