Short-term impacts of Pulse, a Teen Pregnancy Prevention App

Despite years of nationwide declines in teen childbearing, Black and Latinx young women in the United States still experience disproportionately high rates of teen pregnancy.[1] Historically, family planning efforts and teen pregnancy prevention (TPP) programming have not fully met the needs of Black and Latinx young women. For example, women of color often have different attitudes toward birth control than their white counterparts, due to historical racial prejudice in the healthcare system.[2] Additionally, women of color may not always feel represented in the narratives surrounding sexual and reproductive health.[3] Incorporating these topics into programming and tailoring program content to resonate with Black and Latinx populations are needed to increase access to culturally appropriate reproductive health care for women of color.[4],[5]

Administering programming online can also increase access to reproductive health information for Black and Latinx women. For example, TPP programs are often administered in school- or community-based settings where older Black and Latinx teens are not served (either because they have graduated or dropped out of schooling). Administering programming online can bridge this gap and reach populations often left out of more traditional in-person approaches.[6],[7]

Healthy Teen Network designed Pulse, an app-based teen pregnancy prevention program, to address the sexual and reproductive health needs of Black and Latinx young women ages 18 to 20. During the development of Pulse, Healthy Teen Network met with Black and Latinx youth advisors to get feedback on the content and design of the app. Youth from both populations identified common themes related to accessing health services, use of birth control, and attitudes and beliefs about birth control. Pulse designers prioritized these themes and used them to inform the app content and multimedia.

From 2016 to 2019, Child Trends conducted a randomized control trial to evaluate the impact of Pulse on two measures of unprotected sex (sex without any birth control method, and sex without a hormonal or long-acting reversible contraceptive method), as well as the program’s impacts on knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions. The impact results from the six-week short-term follow-up survey were recently published in the Journal of Adolescent Health (JAH).[8] This research brief summarizes the impact findings from the JAH article.

Key Findings

At the conclusion of the six-week Pulse intervention, participants reported their behaviors, knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions through an online survey. Compared to control group participants, Pulse participants:

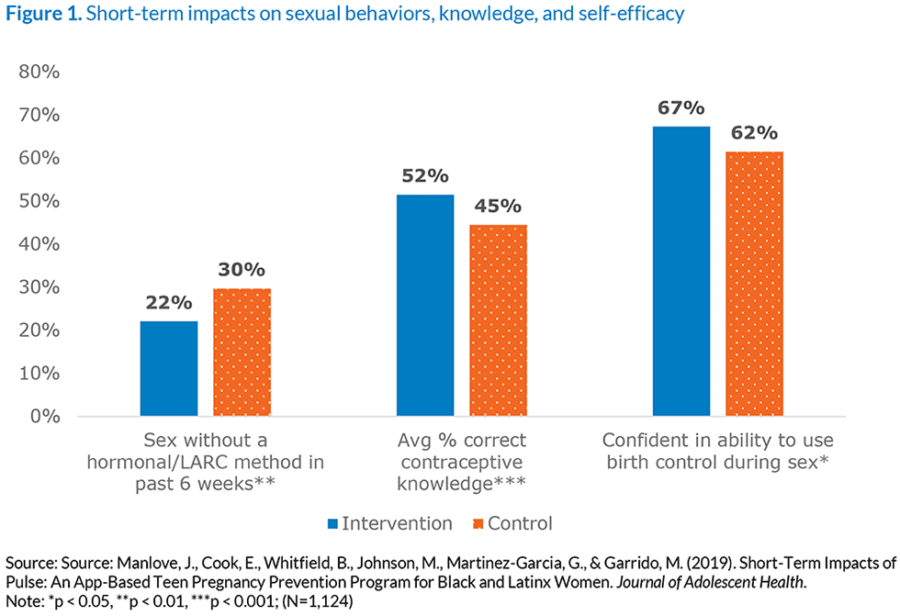

- Were less likely to report having sex recently without using a hormonal or long-acting contraceptive method

- Had more accurate knowledge about contraceptives

- Were more confident that they would be able to use birth control during every sexual intercourse in the future

Background

We recruited 1,304 participants into the study through targeted ads on Instagram and Facebook. Young women who self-identified as Black and/or Latinx women were prioritized[a] since the app was designed for them. To enroll in the study, participants had to meet the following requirements:

- Self-identify as female

- Ages 18 to 20

- Speak English

- Not currently pregnant or trying to become pregnant

- Have daily access to a smartphone

- Currently live in the United States or a U.S. territory

Both the program and the evaluation were fully technology-based, meaning that all recruitment, enrollment, program content, and pre- and post-survey participation took place online, primarily on smartphones. We did not have one-on-one contact with participants unless the participant reached out for assistance. Participants were enrolled between November 2016 and January 2018. They were randomized to either the Pulse intervention app or a control app on general health topics and began their program immediately after being randomized. During the six-week intervention period, participants had unlimited access to their app and received text messages with app-related content. To encourage participants to use the app, we developed targeted text message reminders.

Methodology

Data collection

All study participants took a baseline survey prior to randomization and were invited to complete a short-term follow-up survey six weeks later. To encourage participants to complete the survey, we sent reminder Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) messages and, if needed, called participants to follow up. Eighty-five percent of the Pulse intervention group and 87 percent of the control group completed the post-test survey, so the rate of differential attrition was acceptable.[9]

Outcomes

The primary behavioral outcomes are two measures of unprotected sexual intercourse:

- Sexual intercourse without using any method of contraception

- Sexual intercourse without using a hormonal contraceptive (birth control pills, the shot, the patch, and the ring) or long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method (IUDs and implants)

These outcomes were measured for the full sample, including women who reported never having had vaginal sex. We focused on hormonal and LARC methods rather than all forms of modern contraceptives because Pulse focuses on increasing use of highly effective contraceptive methods.

The secondary outcome measures include:

- Average percent correct of questions regarding contraceptive knowledge

- Attitudes toward birth control and accessing sexual and reproductive health services

- Birth control and sexual and reproductive health self-efficacy

- Intentions related to using birth control and visiting a health care provider for sexual or reproductive health services

Analysis

The study design is a randomized control trial with individual-level random assignment. Baseline equivalence was established between intervention and control groups. Linear probability models were used to assess the impact of Pulse on each outcome for the 1,124 participants who completed the short-term follow-up survey.[10] All analyses controlled for 1) the baseline measure of each outcome, 2) whether participants reported ever having had vaginal sex prior to baseline, 3) age at baseline, 4) and race/Latinx ethnicity. All analyses were completed using Stata 13.1.[11]

In addition to the main impact findings presented here, we investigated the sensitivity of our results to alternative coding of the outcome measures to adjust for data discrepancies. See Appendix A in the PDF brief for details on each of the sensitivity checks conducted. We also conducted interaction analyses, using the linear probability models described above, with data from the 421 Latinx and 430 Black participants who completed the six-week follow-up survey (n = 851) to assess differences in impacts between Black and Latinx participants. However, none of these interactions were significant, indicating there were no differing intervention impacts for Black and Latinx participants.

For additional detail on the study background, design, methods, and limitations, see our recent journal publication here.

Participant characteristics

Among the analytic sample of 1,124 participants who completed the six-week follow-up survey, there were no significant differences between the Pulse intervention and control groups for any measure at baseline. The average age of the sample was 18.8 years, and most of the sample identified as Latinx or Black (76 percent). The sample had high educational attainment, with more than 70 percent having completed some college, technical school, or more. Approximately 69 percent of the sample ever had vaginal sex, 56 percent had sex in the past three months, and 9 percent had ever been pregnant. Participants had high rates of unprotected sex at baseline. One in four participants reported having sex in the past three months without using any contraceptive method, and 28 percent reported having sex in the past three months without using a hormonal or LARC method.

Download

Results

At the end of the intervention period, we found impacts on sex without a hormonal or long-acting method, contraceptive knowledge, and birth control self-efficacy. We did not find impacts on sex without any method of contraception, attitudes toward birth control, sexual and reproductive health self-efficacy, intentions to use birth control, or intentions to visit a health care provider for sexual or reproductive health services.

Sex without a hormonal or long-acting method

At follow-up, Pulse participants were less likely to report that they had sex without a hormonal or long-acting reversible contraceptive method in the past six weeks (22%) than control participants (30%). We did not find significant differences between the intervention and control groups on the second primary outcome, sex without any method in the past six weeks (not shown). The figure below shows participant responses to the survey question “In the past 6 weeks (about a month and a half), have you had vaginal intercourse without using any of these methods of birth control? Birth control pills; The shot (for example, Depo Provera); The patch (for example, Ortho Evra); The ring (for example, NuvaRing); IUD (for example, Mirena, Skyla, or Paragard); Implant (for example, Implanon or Nexplanon).”

Accurate knowledge about contraceptives

At follow-up, Pulse participants had more accurate knowledge of contraceptives (52%) than control participants (45%). The figure below shows the average percentage of correct answers, for each group, across four true/false questions about contraceptives: 1) A condom is more effective at preventing pregnancy than the IUD (intrauterine device); 2) The implant is more effective at preventing pregnancy than the birth control pill; 3) A woman can use an IUD even if she has never had a child; and 4) Long-acting methods like the implant or IUD cannot be removed early, even if a woman changes her mind about wanting to get pregnant.

Birth control self-efficacy

At follow-up, Pulse participants were more likely to agree (67%) that they are confident they would be able to use birth control every time they have sexual intercourse (as opposed to “disagree” or “neither agree nor disagree”) compared to control participants (62%). The figure below shows participant responses to the survey question “I am confident that I can use birth control every time I have sex.”

Conclusions

This study presents short-term impacts from an app-based teen pregnancy prevention program designed primarily for Black and Latinx young women. It is one of the first randomized control trials to assess impacts of an app-based teen pregnancy prevention intervention with online recruitment and data collection. The study reached a large sample of primarily Black and Latinx young women ages 18-20, who are less likely than younger teens to be served by existing pregnancy prevention efforts.

The results show that culturally appropriate, app-based approaches to teen pregnancy prevention programming designed for Black and Latinx young women can have short-term impacts on behavioral outcomes and outcomes associated with unplanned pregnancy, including knowledge about and self-efficacy in using contraception. Our findings suggest that mobile-based approaches can be accessible, convenient, and scalable and can offer a promising approach to sex education. Forthcoming analyses using longer-term data will assess whether the short-term impacts on unprotected sex are sustained through a longer period and test program impacts on pregnancy.

This publication was made possible by Grant Number TP2AH000038 from the Office of Population Affairs (OPA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the OPA or HHS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kate Welti, Dominique Parris, Jenita Parekh, and Jane Finocharo of Child Trends for their contributions to this brief. We would like to thank our JAH co-authors, Genevieve Martínez-García and Milagros Garrido of Healthy Teen Network, for the development of Pulse and their contributions to the article.

Endnotes

[a] Black and Latinx young women were prioritized through targeted social media ad recruitment as well as recruitment caps that limited the number of women who were non-Latinx and non-Black to 20 percent of the sample.

[1] Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Osterman, M.J.K., Driscoll, A.K., & Drake, P. Births: Final Data for 2017. (2018). National Vital Statistics Reports, 67(8). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

[2] Dehlendorf, C., Rodriguez, M. I., Levy, K., Borrero, S., & Steinauer, J. (2010). Disparities in family planning. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 202(3), 214–220. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.022

[3] Price, Kimala. (2011). It’s Not Just About Abortion: Incorporating Intersectionality in Research About Women of Color and Reproduction. Women’s health issues: official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 21. S55-7. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.003.

[4] Prather, C., Fuller, T.R., Jeffries IV, W.L., Marshall, K.J., Howell, A.V., Belyue-Umole, A., King, W. (2018). Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health: a review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity, Health Equity 2:1, 249–259, DOI: 10.1089/heq.2017.0045.

[5] Russell, S. T., & Lee, F. C. (2004). Practitioners’ perspectives on effective practices for Hispanic teenage pregnancy prevention. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 36(4), 142-149.

[6] Juras, R., Tanner-Smith, E., Kelsey, M., Lipsey, M., & Layzer, J. (2019). Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention: Meta-Analysis of Federally Funded Program Evaluations. American Journal of Public Health, 109(4), e1-e8. doi:10.2105/ajph.2018.304925

[7] Lugo-Gil, J., Lee, A., Vohra, D., Harding, J., Ochoa, L., & Goesling, B. (2018). Updated findings from the HHS Teen Pregnancy Prevention Evidence Review: August 2015 through October 2016. Washington, DC: Office of Population Affairs, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from: https://tppevidencereview.aspe.hhs.gov/pdfs/Summary

_of_findings_2016-2017.pdf

[8] Manlove, J., Cook, E., Whitfield, B., & Johnson, M. (2019). Short-Term Impacts of Pulse: An App-Based Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program for Black and Latinx Women. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.017

[9] Deke, J., Sama-Miller, E., & Hershey, A. (2015). Addressing Attrition Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials: Considerations for Systematic Evidence Reviews. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from: https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/addressing-attrition-bias-in-randomized-controlled-trials-considerations-for-systematic-evidence

[10] Deke J. (2014). Using the Linear Probability Model to Estimate Impacts on Binary Outcomes in Randomized Controlled Trials. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. Report No. 6. Retrieved from: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/sites/default/files/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/assets/lpm-tabrief.pdf

[11] StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013.

Download

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube