Racism and Discrimination Contribute to Housing Instability for Black Families During the Pandemic

This brief is the third in a series examining timely topics that are relevant to Black families and children in the United States. It uses national, state, and local data to examine housing access and other available supports for Black families, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first brief provides a brief summary of recent data and historical context on family structure, employment and income, and geography for Black people with young children in the United States. The second brief sheds light on the role of federal policies in creating, maintaining, and addressing these structural inequities, with a specific focus on access to early care and education for Black families.

Download

Housing that is affordable, high-quality, and stable is fundamental for supporting families’ health and well-being. This issue brief presents recent data on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black families’ access to stable housing in the United States and, at the local level, in Newark, New Jersey. Newark, a predominantly Black city, has a history of fighting racist policies and practices and was at the forefront of the 1960s’ protests for civil rights in America. It is also one of the poorest cities in the nation, where residents have lacked access to affordable housing for decades. Newark currently has progressive housing policies aimed at promoting residential stability. In fact, Newark was one of the first cities in the nation to enact a right to counsel law, guaranteeing legal counsel for residents facing eviction. Despite this effort, the supply of affordable housing is still extremely limited, and while the current mayor of Newark is working to address this situation, Newark residents—particularly those who have lower incomes—continue to face persistent challenges in finding affordable, high-quality, stable housing.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted the health and well-being of individuals—like Black Americans—who have been historically disadvantaged in the United States. More specifically, the pandemic has exacerbated longstanding inequities in income, food security, and access to affordable, stable housing for Black families. These existing inequities are an extension of the nation’s history of systemic and institutionalized racism, including discriminatory housing policies. While there are temporary eviction moratoria in place at the federal, state, and local levels to protect families from eviction and foreclosure, millions of households—including many with children—are facing housing instability and potential homelessness in the wake of the pandemic; this is especially the case for Black and Latino households. Housing stability is an important determinant of children’s health and well-being. Given that Black families are more likely to be disproportionately impacted by discriminatory housing practices and policies, they are also more likely to experience housing instability. Therefore, it is critical to understand their housing needs in order to ensure equitable access to stable housing.

The findings in this brief are drawn from two data sources. First, we highlight national findings from a Child Trends analysis of the Household Pulse Survey (HPS).[1] Next, we provide a summary of findings from a study of the housing needs of Black families during the pandemic, in a predominantly Black community in Newark, New Jersey: the South Ward.[2] In this brief, the national data provide context for local data to demonstrate the role of housing discrimination. We also discuss the role of discrimination in housing access and provide recommendations for local policymakers and leaders to promote the equitable distribution of housing supports as increased opportunities to address housing policy issues occur in response to the pandemic.

Definitions

Due to the pervasive nature of structural racism in the United States, no Black person in America (regardless of their country of origin or ancestry) is immune from the effects of racism. However, the historical context of an individual’s country of origin or identification may vary; this, in turn, has the potential to differentially impact the experiences of Black people in the United States.

When referencing Black people throughout this issue brief series, we are referring to individuals who may identify as African American—those who were primarily born in America and are descended from enslaved Africans who survived the trans-Atlantic slave trade—as well as the smaller populations of people living in America who may identify as Black African or Afro-Caribbean.

Black also includes individuals who reported being Black alone or in combination with one or more races or ethnicities in their responses to the U.S. Census—for instance, an individual who identifies as Black only, as well as someone who identifies as Black and White combined or Afro-Latino.

Findings

National findings on Black families’ housing needs during the pandemic

The national findings are based on an analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s HPS data, collected from February 3–15, 2021, to facilitate understanding about the housing crisis for Black families. Our analysis focuses on adults with children who reported living in a renter or homeowner household (i.e., housing that is either rented, or owned with a mortgage or loan, by the respondent or another person in the household).

- More than 1 in 6 (17%) adults in renter or homeowner households with children reported that they were not “caught up” on rent or mortgage. This is driven largely by renter households, of whom 25 percent reported being behind on rent. Black[3] households in particular reported not being caught up on rent or mortgage (close to 1 in 3 households, or 30%).

- One (1) in 4 U.S. adults (24%) in households with children reported limited confidence that their household would be able to make their next rent or mortgage payment on time. Among Black households with children, 40 percent reported limited confidence in their ability to pay on time.

- Of those not up to date on rent or mortgage, 36 percent of all households with children—and 50 percent of Black households with children—said that eviction or foreclosure was somewhat or very likely in the next two months.

Findings from the South Ward of Newark, NJ

Currently, New Jersey residents have more housing protections than residents of many other states, with an eviction and foreclosure moratorium that is slated to remain in place until two months after the governor declares the COVID-19 crisis over (unless a federal Executive Order ends it sooner). The moratorium does not, however, include a rent/mortgage freeze or stop court proceedings, which means that individuals and families can be removed from their residence as soon as the order is lifted. From March 2020 through October 2020, 45,600 eviction notices had been filed in the state.

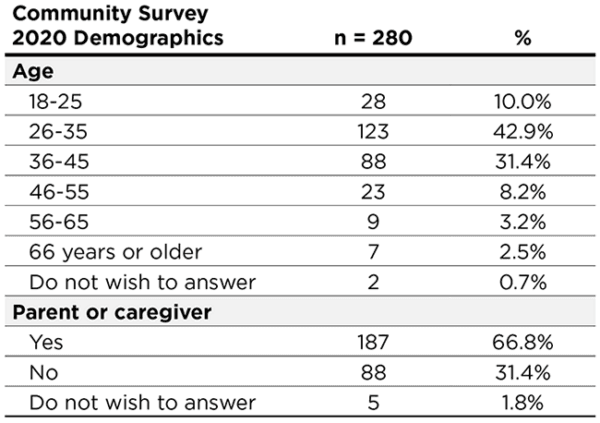

The following findings are based on preliminary Child Trends analyses of a community survey of 280 residents and in-depth interviews with five residents in the South Ward in Newark, NJ. For additional details on survey respondents, please see Table 1 below. The following analyses include responses specifically from survey respondents and interviewees who identified as Black.

Table 1. Survey respondent age and parental status

Source: Authors’ analysis of South Ward community survey data

Discrimination limits access to stable, high-quality, affordable housing.

Housing discrimination may prevent families from accessing affordable, stable housing due to biases against certain characteristics of their household. Discrimination based on race, ethnicity, family size, income, and criminal history further impacts families’ ability to find stable, affordable living accommodations. While discrimination occurred prior to the pandemic, it will be an important issue to monitor as families’ need and searches for housing are forecasted to increase because of the pandemic.

Survey and interview data indicate that:

- Among South Ward residents who identified as Black and who completed the community survey, 21 percent reported experiencing discrimination at some point when looking for affordable, high-quality, and stable housing. Of those who reported discrimination, 78 percent reported more than one reason for discrimination, including their, or their spouses’, race or ethnicity.

- Interview respondents also reported housing discrimination as a result of having a child, their income, or a criminal or bad credit history. When asked directly in their interviews, not all respondents reported that they had experienced discrimination. However, over the course of the interviews, many respondents provided unprompted examples of discriminatory practices when asked about other topics. This finding is in line with other research, which has revealed that discriminatory practices related to housing are often underreported and may not be labeled as such, often due to their subtle and changing nature.

The pandemic has made it difficult for renters and homeowners to meet their housing costs.

- The majority (65%) of renters and mortgage payers[4] who responded to our survey were not able to pay their rent or mortgage in full and on time during the time of the survey (August and September 2020). Thirteen percent (13%) of renters and mortgage payers who responded to the survey indicated that they had not paid their last month’s rent or mortgage on time. Another 52 percent reported only being able to partially pay their mortgage or rent on time. Furthermore, over one quarter (28%) of respondents indicated that they have only slight or no confidence that they will be able to pay next month’s rent or mortgage.

- Meeting housing costs during the pandemic may be particularly challenging for renters. Fifty two percent (52%) of renters reported missing or delaying a payment since the start of the pandemic. Additionally, 22 percent of these renters who had missed or delayed a payment reported receiving an eviction notice in the past year; most of these (55%) were reported since the start of the pandemic.

- South Ward residents also reported tensions with their landlords over missed payments. One resident stated, “My landlord sent me a letter. He’s trying to give me a deadline now; I need to get assistance, or I will be facing eviction and then where do I go from there?”

Residents further reported that landlords were being inflexible during the pandemic. “… [I] was in the same residence for four years, had good rapport with the landlord; when I hit rock bottom, he wasn’t understanding and that hurt because I didn’t expect that. I only ever showed him I was reliable and respectable, [a] paying-on-time tenant.”

Of the residents interviewed, housing quality was also a problem. Residents highlighted that market rates for housing are high compared to residents’ incomes in the South Ward, and that available affordable housing is of poor quality and located in areas with high rates of violence, drug use, and other illegal activity. They also reported limited access to housing that can accommodate individuals with disabilities.

The pandemic is increasing housing instability[5] and homelessness.

- Residents in the South Ward and the surrounding area are facing a great deal of housing instability during the pandemic. Of the survey respondents, 27 percent reported moving at least once during the pandemic (8% reported moving two times and 12% reported moving three or more times).

- Among all participants, 71 percent reported living in their own home. An additional 5 percent reported living in their parents’ or guardians’ home (young adult respondents only), and 12 percent with friends, family, or other people (while paying rent). Eleven percent (11%) reported housing instability or homelessness (see next bullet). One percent (1%) did not wish to answer the question.

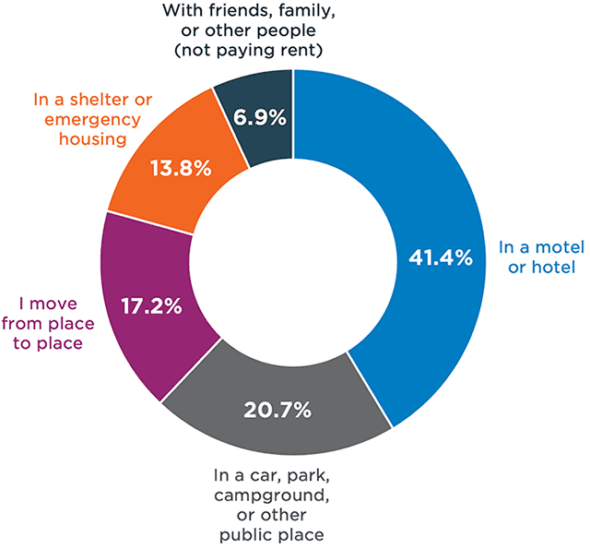

- South Ward residents reported experiencing homelessness and housing instability at a higher rate than national estimates. Among the 11 percent of respondents who reported homelessness or housing instability, 41 percent reported that they had “usually slept” in a motel or hotel in the last 30 days; 21 percent had slept in a car or other public place, 14 percent reported they had slept in a shelter or emergency housing program, and 7 percent had slept in someone else’s home where they did not pay rent due to economic hardship. Seventeen percent (17%) indicated that they had moved from place to place (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Current living arrangements among South Ward respondents experiencing homelessness and housing instability, past 30 days (November 2020)

Source: Authors’ analysis of South Ward community survey data

One concern for residents in the South Ward is the length of time needed to receive housing supports. One resident who previously experienced homelessness reported, “The waiting list is so long [for] Section 8,[6] low-income housing … It would be better because rental market is so high, so sometimes you can’t afford [market rent housing]. If I had been in subsidized housing it would have prevented it [homelessness].”

Summary of findings

Local data from the South Ward community in Newark, NJ indicate that families who are Black and rent their housing face challenges in securing and remaining in their housing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While national and local data suggest similar patterns, data from the South Ward, a predominantly Black community, provide a more nuanced picture of housing needs for Black families during the pandemic. These data suggest that federal, state, and local policies and programs to support renters are not always sufficient, even in New Jersey, which has more generous policies than other states. This results in extremely high rates of homelessness and housing instability, both before and during the pandemic. Homelessness and housing instability may be due in part to delays in gaining access to housing supports, along with limited supports and flexibility from landlords. Additionally, discrimination based on race, ethnicity, family size, income, and criminal history further impacts families’ ability to find stable, affordable living accommodations.

Recommendations

Given the continuing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on families’ health and well-being, a policy agenda that specifically addresses disparities in access to basic needs is fundamentally important. The following recommendations are for local policymakers and community leaders interested in supporting equitable access to housing supports.

- Assess community-specific needs. The approaches and solutions that work for one community may not be right for another. The South Ward Promise Neighborhood and Child Trends conducted a community survey in Fall 2020 as part of their Promise Neighborhood grant. The survey provided real-time, detailed data on the needs of residents in the community during the pandemic. Local leaders should consider conducting similar surveys or other methods for assessing their communities’ housing needs.

- Work with local organizations to ensure that both residents and property owners are aware of tenant rights and anti-discrimination laws. Residents may not be aware of their rights as renters. For example, although New Jersey has anti-discrimination renter policies in place, 22 percent of Black residents in our survey reported experiencing discrimination when searching for housing; this number may actually be underreported. Landlords, tenants, and realtors should be well versed in the community’s anti-discrimination laws, as well as with the agencies that can provide support should discriminatory practices occur.

- Raise community awareness of housing support programs, particularly for Black renters. National data indicate that Black families’ ability to pay rent changed quickly due to pandemic-related job and income loss. Landlords’ inflexibility led to families’ inability to maintain stable housing. However, as other publications have noted, landlords themselves—particularly small landlords—are having a difficult time meeting their own housing costs because of the pandemic. Housing support programs for both tenants and landlords may be helpful. Renters, however, must be made aware of the available options in order to benefit from them. Advertising on social media and providing information in public spaces that are easily accessible may be particularly helpful. One interview participant noted, “I feel like others are in this situation due to the pandemic. It’s hard. I’m in [social media group] and everyone in that group talks about rental assistance because it’s hard with this pandemic and the rent. A lot of people lost jobs.”

About the authors

Chrishana M. Lloyd, a senior research scientist and early childhood expert, and Sara Shaw, a research scientist and housing expert—both of Child Trends—are the co-lead authors on this brief. They were supported by Marta Alvira-Hammond and Alex DeMand of Child Trends, and by Ashley M. Hazelwood of the South Ward Promise Neighborhood.

Download

References

[1] The Household Pulse Survey is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in collaboration with other federal agencies to quickly and regularly release data on the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. households.

[2] Child Trends is currently serving as the external evaluator for the South Ward Promise Neighborhood initiative, a federally funded project designed to positively affect the life trajectories of children and families in under-resourced communities. One priority of the South Ward Promise Neighborhood initiative is to support equitable access to housing for families living in the South Ward.

[3] Race/ethnicity designation in Pulse findings is based on the reported race/ethnicity of the respondent.

[4] This does not include those who had deferred payments (5.2%).

[5] Housing instability refers to families residing in temporary accommodations.

[6] Housing Choice Voucher Program Section 8 provides a housing subsidy directly to landlords in households chosen by recipients.

Methods

Household Pulse Survey

We use data from the Household Pulse Survey’s (HPS) to examine housing stability among households with children in the United States. The HPS is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau in collaboration with other federal agencies to quickly and regularly release data on the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. households. We draw from Public Use Files for Phase 3 Week 24 data (February 3–15, 2021). Estimates are weighted using household survey weights provided in the data files.

For estimates of being caught up on rent, confidence in ability to pay the next rent/mortgage on time, and likelihood of eviction or foreclosure in the next two months, we restricted analyses to respondents in households with any children under 18; who reported that their home was either rented or owned with a mortgage or loan (versus “owned free and clear”); and who did not have missing data on any of the three items, for total sample size of N=16,386 respondents and n=1,384 non-Hispanic Black respondents.

The survey has a relatively low response rate, introducing some level of nonresponse bias. The Census Bureau also made the survey longer, which resulted in more response drop-off toward the end of the survey, which includes the housing items. Nonresponse is also higher among groups more likely to face challenges in housing, employment, and other areas, including younger people and people of color. Thus, the estimates presented here may be conservative.

South Ward Community Data

South Ward Community Survey

In August 2020, Child Trends conducted a survey in the South Ward community as part of a larger external evaluation of their Promise Neighborhood initiative. We use preliminary findings from this survey to illustrate housing needs in the community. The survey was administered electronically, and residents received links through mailers, emails, or social media. In total we received responses from 280 community members who identified as Black or African American.

We were not able to randomly assign survey participants due to the pandemic, therefore this is not a representative sample of the community. We have provided a table in the brief to describe the demographic makeup of our sample. Additionally, respondents were not required to include their zip code on the survey. Therefore, it is possible that some respondents live outside of the South Ward community.

Interviews with South Ward Residents

In addition to the community survey, we conducted interviews with five South Ward residents to help provide further context to the survey. These residents included both parents, and single adults. Interviews were conducted in November 2020 by phone. In addition to residents, we attempted to contact landlords for their point of view. At the time of the interviews, we were not able to successfully contact any landlords for participation.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube