More than One in Four Latino and Black Households with Children Are Experiencing Three or More Hardships during COVID-19

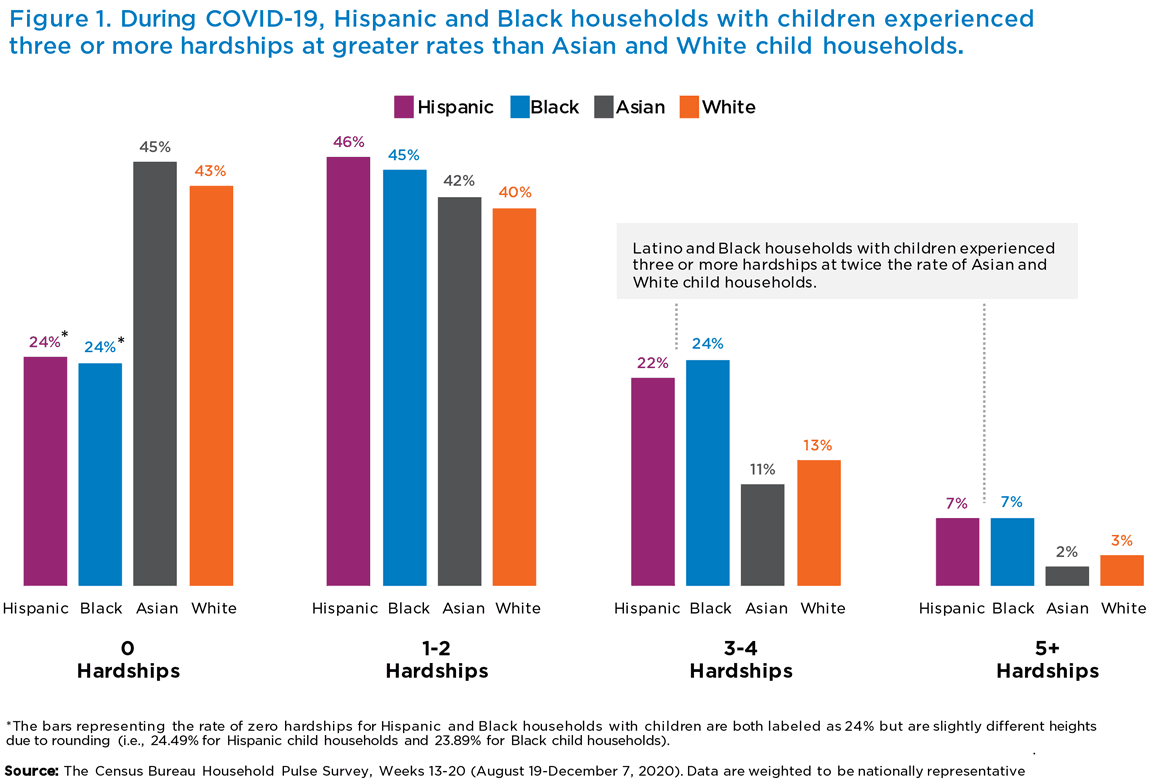

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of families experiencing hardships across the country has risen dramatically, with a disproportionate impact on Latino* and Black communities. Twenty-nine percent of Latino and 31 percent of Black households with children are experiencing three or more co-occurring economic and health-related hardships as a result of the pandemic, according to recent data. This is nearly twice the rate among Asian and White households with children (13% and 16%, respectively).

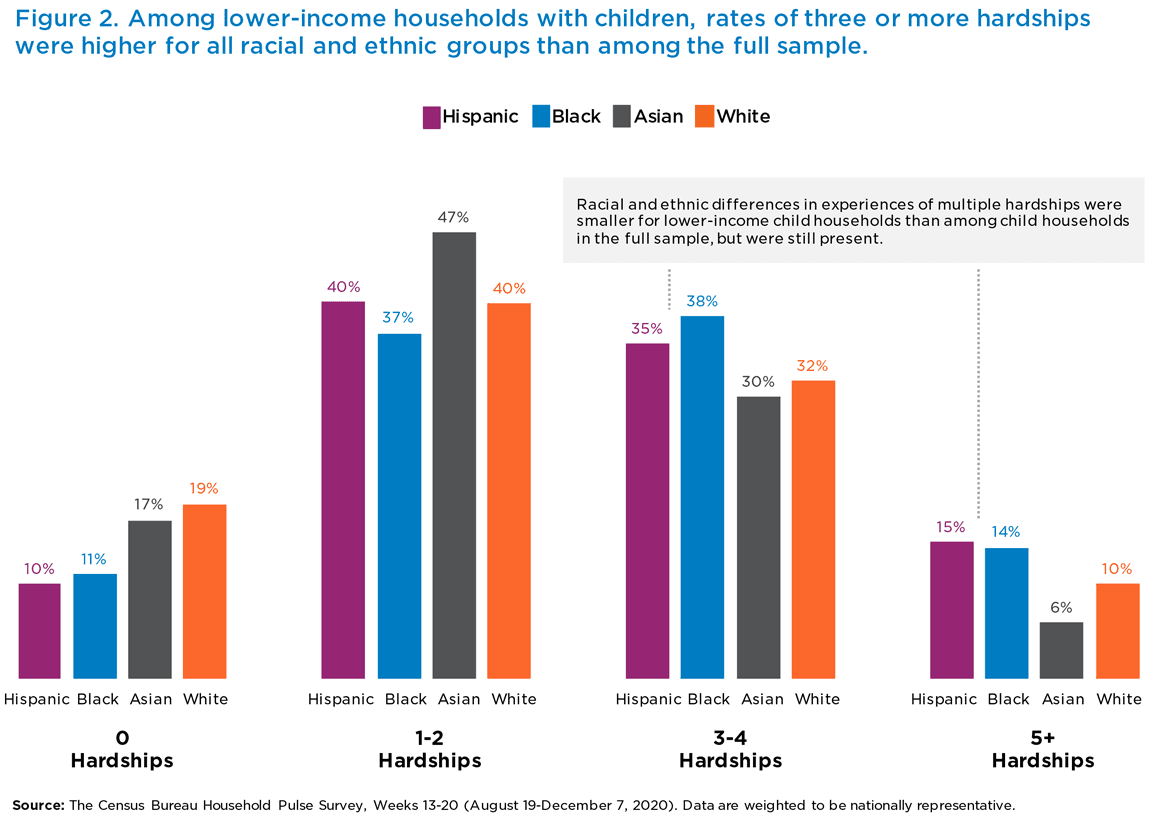

Disparities in experiencing multiple, co-occurring hardships were not fully explained by racial and ethnic differences in income in our analysis; Hispanic and Black low-income families also experienced multiple hardships at greater rates than Asian and White low-income families. These racial and ethnic disparities in the experience of multiple co-occurring hardships underline the structural inequities embedded in our nation’s institutions, as well as policies that continue to make it difficult for Latino and Black families to achieve sufficient economic stability to weather unexpected income disruption, such as a job loss or medical emergency.

For the analysis presented in this brief, we used nationally representative data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which has tracked the well-being of U.S. households during the pandemic, to examine seven types of hardships: unemployment, difficulty paying expenses, not being caught up on rent or mortgage, food insecurity, physical health problems, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and lack of health insurance. We analyzed these reports of hardships across Latino, Black, Asian, and White households with children—first across all income groups and then among households with low incomes, defined as those with self-reported pre-tax 2019 incomes of less than $50,000.

* We use the terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” interchangeably throughout. Latinos may be of any race. We use the terms “White,” “Black,” and “Asian” to refer to non-Hispanic individuals.

This brief is a joint publication from Child Trends and the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Context

Hispanic and Black individuals are more likely to have contracted, been hospitalized due to, and died from the coronavirus; to have lost a job; to have lost income; to have had trouble paying housing expenses; and to have experienced food insufficiency during the pandemic, compared to White individuals. Systemic barriers to higher education (in terms of access and affordability) for Latino and Black individuals mean that they often work in lower-wage jobs, which are less likely than higher-wage jobs to include a range of benefits, including paid sick leave and health insurance coverage—both essential resources during a global public health crisis.

Even among those with the same job, significant wage gaps rooted in discrimination mean that Hispanic and Black workers, on average, take home less money than White and Asian workers, making it more difficult to keep up with household expenses, including food and housing costs. Compounding these difficulties, Latino and Black families are less likely to have economic buffers during periods of hardship. This is primarily due to systemic factors, like discrimination in housing policies, that limit Black homeownership and to systems that perpetuate racial/ethnic gaps in wealth distribution, such as inheritances and university legacy policies, which overwhelmingly benefit those with White parents. Discrimination contributes to the tendency for Hispanic and Black individuals to receive less and lower-quality physical and mental health treatment and to experience greater barriers to accessing social safety net services.

Combined, these factors make it much more likely that Hispanic and Black families will experience not just a single, temporary stressor, but an accumulation of multiple hardships—particularly during a period of economic instability like the COVID-19 pandemic. While most children are resilient in the face of singular or time-limited stressors, especially when supported by sensitive and responsive caregivers, exposure to multiple, simultaneous, or long-lasting hardships may potentially overwhelm a child’s stress-response system. This, in turn, can impact their attention and regulation of emotion, with the potential for detrimental effects on their learning, behavior, and health. This accumulation of stressors can also overwhelm adults’ psychological resources, making government resources more important than ever—especially those that help parents remain economically afloat and able to financially and psychologically support their children in times of hardship.

A range of structural inequities and systemic barriers make it much more likely that Hispanic and Black families will experience not just a single, temporary stressor, but an accumulation of multiple hardships—particularly during a period of economic instability like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Findings

- Latino and Black households with children experienced three or more hardships at twice the rate of Asian and White child households. Twenty-nine percent of Hispanic and 31 percent of Black households with children have experienced three or more hardships, compared to 13 percent of Asian and 16 percent of White households with children (Figure 1).

- Seven percent of Hispanic and Black households with children experienced five or more hardships, compared to 2 percent of Asian and 3 percent of White child households.

- By contrast, just under half of Asian and White households with children (45% and 43%, respectively) reported experiencing none of the hardships included in our analyses, compared to nearly one quarter of Latino and Black households (24% for both groups).

- Among lower-income households with children (see Figure 2), reports of experiencing multiple hardships were more common across all racial/ethnic groups. The rates at which lower-income households with children experienced zero hardships was less than half that of the full sample. Still, racial/ethnic differences in the rates of multiple hardships were present, although smaller than in the full sample. Lower-income Asian households with children were most likely to experience one to two hardships. Roughly 35 and 38 percent of low-income Hispanic and Black child households, respectively, experienced three to four hardships, compared to 30 percent of low-income Asian and 32 percent of White child households. About 15 percent of Latino and Black low-income households with children experienced five or more hardships, compared to just 6 percent of Asian and 10 percent of White child households with low incomes.

Discussion

Both the federal government and individual states have taken several steps to mitigate the economic hardship stemming from the pandemic—including the provision of direct cash assistance, expanded unemployment insurance, paid family leave benefits, and eviction moratoria. Most recently, in late December 2020, the COVID-19 Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act was signed into law, with a wealth of nutrition, economic, and family supports.

However, access to state and federal resources throughout the pandemic has varied among families with different characteristics. While uptake rates differ considerably by state, regardless of race and ethnicity, unemployed Hispanic and Black workers are less likely than White workers to receive unemployment insurance benefits. In addition, families without access to banks and families with incomes below the threshold for filing taxes may be missed by tax system-based economic relief packages. Some immigrant and mixed immigration-status families may face additional barriers to accessing existing resources and services, as well as COVID-19-specific relief.

One notable limitation of the Household Pulse Survey data is that information on characteristics that could meaningfully differentiate households within racial and ethnic groups—such as household members’ immigration status—was not available. We were therefore unable to capture the diversity within racial and ethnic groups in the present analyses. Furthermore, those who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or multiple race categories were combined by the Census Bureau into one category in the Household Pulse data. We did not include this category in our analyses due to concerns about the small sample size and larger relative variation in estimates, compared to other groups.

Research is needed to better understand the specific features of policies and their implementation that play a role in perpetuating racial and ethnic inequities, as well as the sorts of policies that will best support the families most likely to experience multiple hardships. In light of the prevalence and the deleterious effects of co-occurring hardships, there is a need for integrated systems that more seamlessly connect families who are eligible for one type of support with other supports for which they are likely eligible. States should also consider making permanent some of the temporary reductions to administrative barriers—in-person interviews, in-person benefit issuance, waiting periods, and time limits—that impede access to and timely receipt of the supports that buffer against the cascade of material and psychological hardships that co-occur when families lack sufficient resources to withstand the financial shocks of job loss or sickness. In addition, policymakers should consider issuing specific guidance—such as that recently published by the U.S. Small Business Association—on implementing policies and programs to ensure equitable access to needed supports.

While many families need more support to weather the negative effects of multiple hardships stemming from the pandemic, some may also be experiencing unanticipated benefits of the pandemic that buffer some of these negative effects. For example, one study found that parents with more time at home with their children, due to pandemic-related school closures, reported more positive parent-child interactions than before the pandemic, despite also reporting increased stress. Parents in the study who lost jobs but did not lose income similarly reported more positive parent-child interactions than prior to the pandemic. However, parents who did experience loss of income, along with a job loss, reported greater stress and depressive symptoms. This again points to the toll of an accumulation of hardships, as well as the need for income support during times of financial stress.

Related Research

- During COVID-19, 1 in 5 Latino and Black Households with Children Are Food Insufficient

- Resources for Supporting Children’s Emotional Well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Majority of Low-income Hispanic and Black households Have Little-to-no Bank Access, Complicating Access to COVID Relief Funds

Notes

Results are based on individuals’ responses to the U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, collected from August 19 to December 7, 2020, and are weighted to be nationally representative (unweighted full sample household n=248,334; unweighted lower-income sample household n=48,100). We did not include data collected before August 19 because data on some of the hardships included in these analyses (i.e., difficulty paying expenses, not being caught up on rent or mortgage) were not available prior to that date. We used respondent self-reported data on race and ethnicity to assign households to Hispanic (of any race), non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic White. We included seven hardships in the analysis:

- Unemployment due to COVID-19 (respondent indicated that they did not work in the past seven days due to COVID-19-related reasons, such as being laid off due to the pandemic, being sick with the coronavirus, experiencing coronavirus symptoms, caring for someone with coronavirus);

- Difficulty paying household expenses (respondent indicated that it was somewhat or very difficult to pay usual household expenses in the last seven days);

- Household behind on housing expenses (respondent indicated that the household was not currently caught up on rent or mortgage payments);

- Food insufficiency (respondent reported that anyone in the household sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat in the last seven days);

- Poor physical health (respondent reported that they were in fair or poor health);

- Poor mental health (respondents reported that they had symptoms of an anxiety or a depressive disorder in the last seven days);

- Lack of health insurance (respondent indicated that they were not covered by public or private health insurance or had only Indian Health Service coverage [the decision to consider those with Indian Health Service coverage only as uninsured was made to be consistent with whom the Census Bureau considers to be uninsured]).

The median household size among households with children in the data was four; we chose $50,000 as the cutoff for being considered low-income because it is approximately 200 percent of the federal poverty level for a family-size of four. Respondents were included in analyses if they had non-missing data on two or more hardships; households with missing data on two to six indicators were counted as not having the hardship(s) they were missing. For this reason, our estimates likely underestimate the number of hardships experienced by some families. Furthermore, many respondents did not answer questions about housing in the Household Pulse Survey, so our measure of difficulty paying housing expenses is also an underestimate.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube