Measuring Gender Attitudes and Norms among Adolescent and Young Adult Males in the United States

Previous research has linked rigid gender norms with increased intimate partner violence and poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes. Teen pregnancy prevention programs that address rigid gender norms may help youth foster more gender-equitable attitudes and healthier relationships and, ultimately, avoid unintended teen pregnancies. However, it can be challenging to use surveys to measure changes in gender norms that may result from these interventions, as many commonly used scales were not developed with modern U.S-based adolescents in mind. Moreover, gender attitudes and norms encompass a number of underlying domains that may vary by population, and intervention programs may choose to target only certain domains.

This brief provides program developers, implementers, and evaluators with survey items and outcome measures to consider when assessing participants’ attitudes around gender norms. Findings are based on an analysis of underlying gender norm and attitude factors that are most salient to a sample of mostly Black and Latino adolescent males. Survey items are drawn from Child Trends’ evaluation of Manhood 2.0, an innovative teen pregnancy prevention program developed by Promundo for young men. The program examines rigid gender norms and partner communication about sex and aims to prevent intimate partner violence and support female partners in contraceptive use. The program was evaluated with mostly Black and Latino young men, ages 15 to 18, in the Washington, DC metropolitan area.

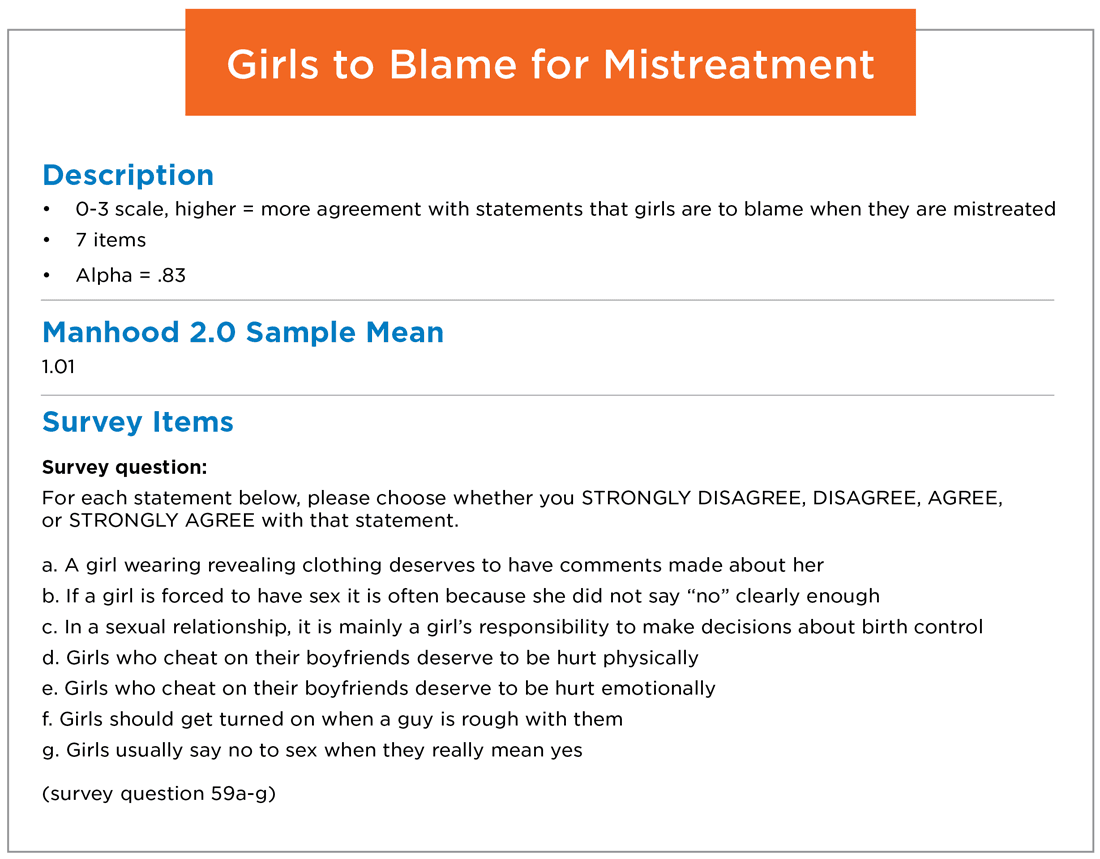

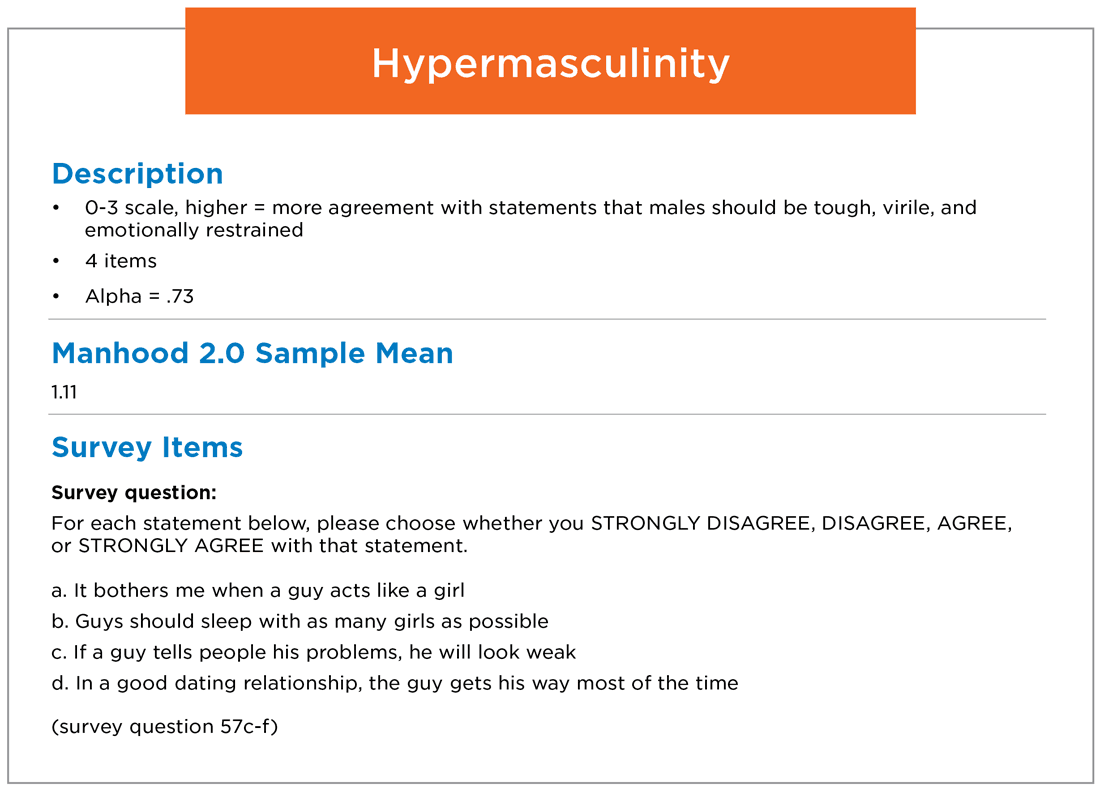

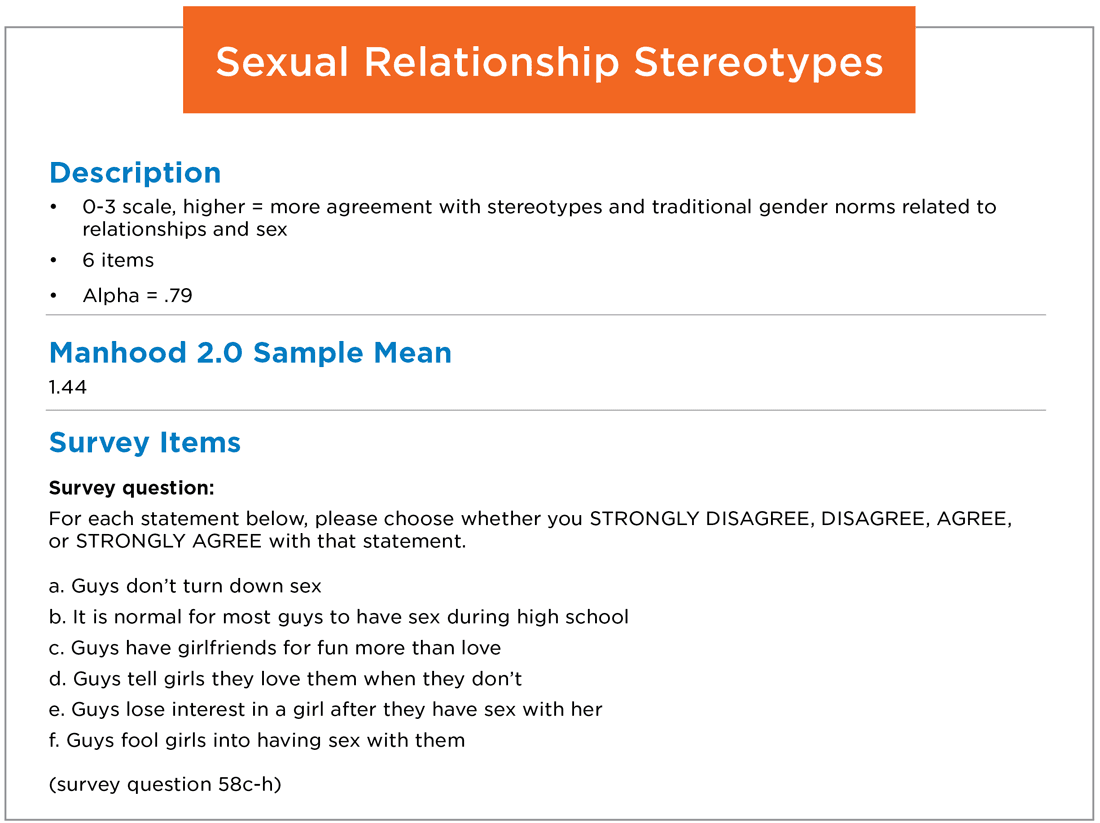

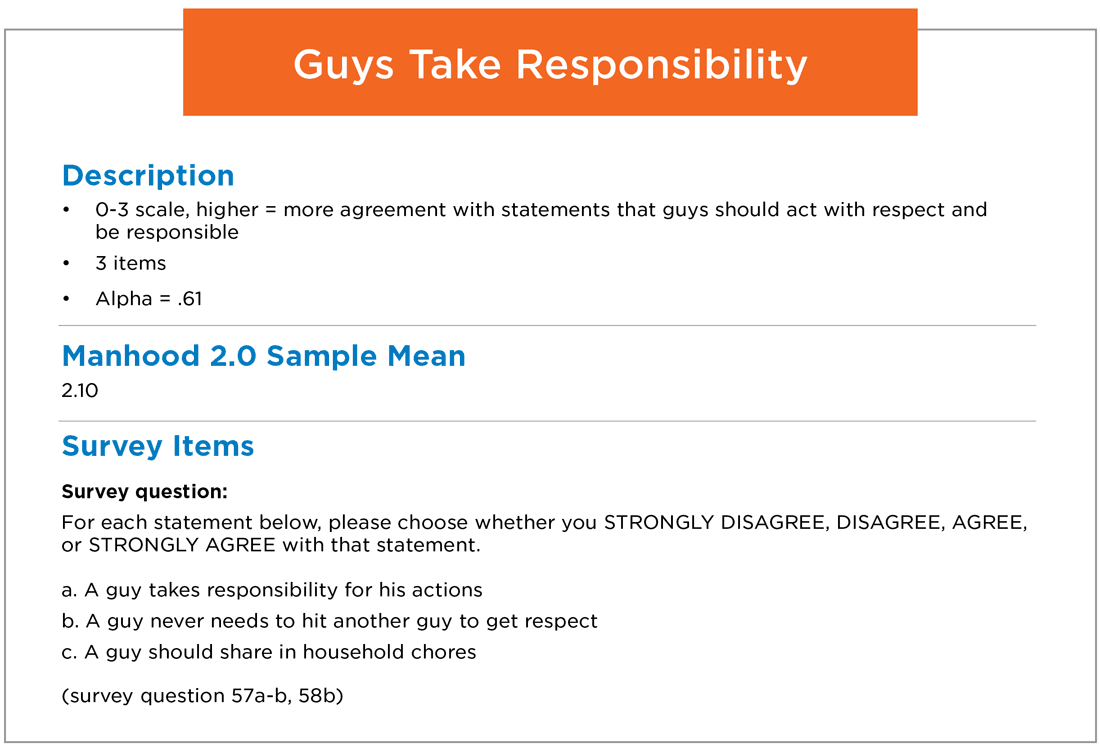

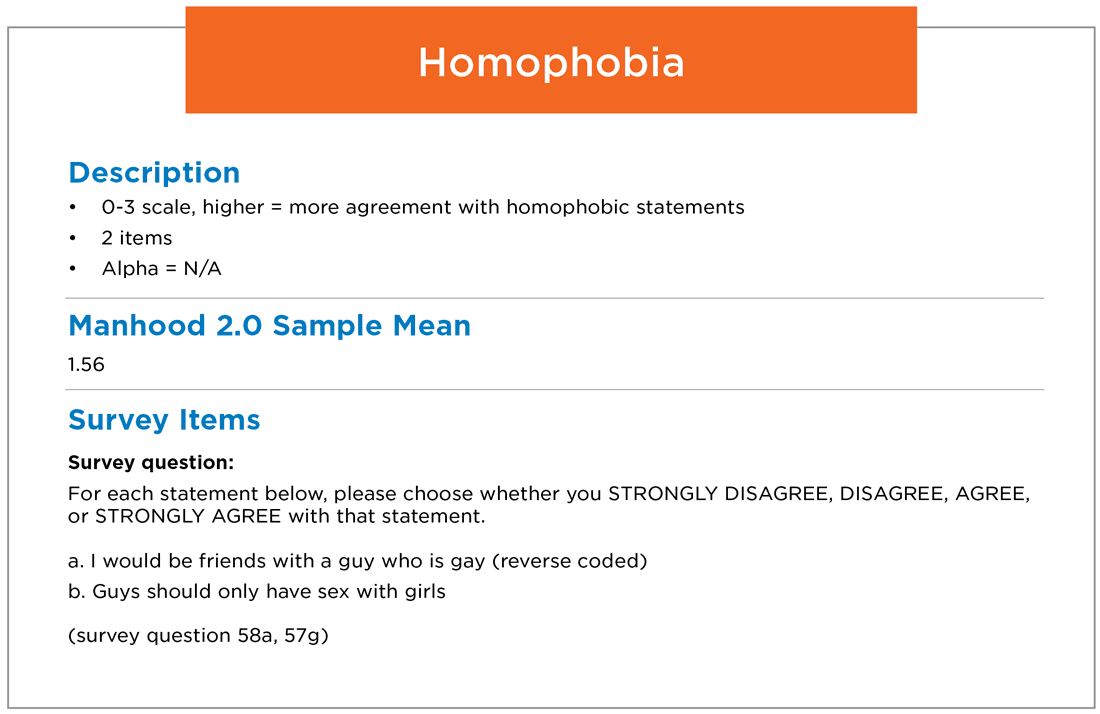

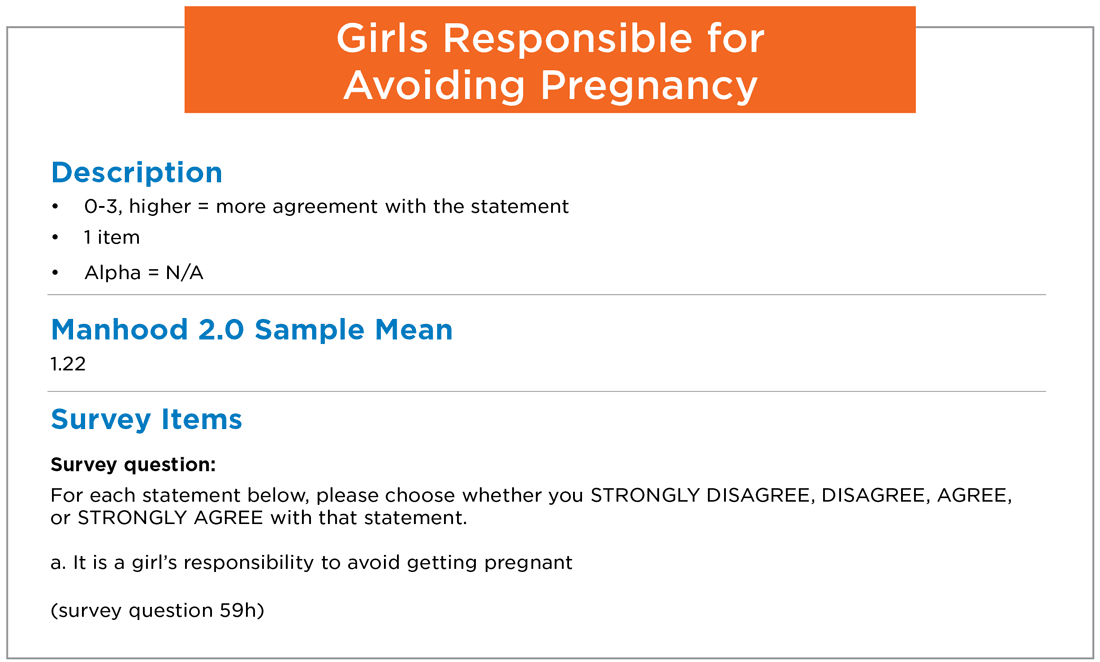

As part of this evaluation, Child Trends examined responses to 23 survey items related to gender norms and attitudes, based on original or adapted measures from several existing surveys. Through exploratory factor analysis, we identified six underlying factors that describe adolescent males’ attitudes toward gender norms. From these factors, we created the following measures for analysis: Girls to Blame for Mistreatment, Hypermasculinity, Sexual Relationship Stereotypes, Guys Take Responsibility, Homophobia, and Girls Responsible for Avoiding Pregnancy. Below, we provide information on each measure, including the mean value at baseline for the Manhood 2.0 sample, the relevant survey items, and the survey question source(s). The full survey can be accessed here.

Survey Item Sources

a-b: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) scale

c: Attitudes Related to Condom and Contraceptive Use scale, adapted from Borrero et. al

d-e: Adapted from the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) scale

f: Attitudes Toward Sexual Control scale

g: Adapted from the Attitudes Toward Women (AWS) scale

Survey Item Sources

a-b: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) scale

c-d: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationship (AMIRS) scale

Survey Item Sources

a: Adapted from the Man Box scale, Manhood 2.0

b: Created by Child Trends

c-f: Global Early Adolescent Study (GEAS)

Survey Item Sources

a, c: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) scale

b: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationship (AMIRS) scale

Survey Item Sources

a: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationship (AMIRS) scale

b: Gender-Equitable Attitudes scale, adapted from the Gender-Equitable Men (GEM) scale

Survey item selection and adaptation

The complete survey, administered to 110 Manhood 2.0 participants, assessed demographic characteristics; sexual risk behaviors; and questions about intentions, knowledge, attitudes, gender norms, skills, and self-efficacy that are associated with relationship violence and unintended pregnancy—all topics targeted by the Manhood 2.0 curriculum. Survey items related to gender norms (as seen above) sought to measure whether the program resulted in more equitable attitudes around gender norms and masculinity among the young men. Items were based on both original and adapted measures from several existing surveys, including the Gender Equitable Men (GEM) scale, the Gender Equitable Attitudes scale, and the Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationship (AMIRS) scale, among others.

All survey items were subject to cognitive testing with male and female middle and high school students as part of a separate federal teen pregnancy prevention program evaluation during the same period (full survey available here). Cognitive interviews ensured that participants could easily understand and accurately interpret the survey items and confirmed that respondents had the information they needed to answer the questions. Survey items utilized in the Manhood 2.0 survey were adapted based on these findings. Finally, the study team chose survey items that were appropriate for male respondents; however, if researchers are studying a female or coed sample, other items could be considered to understand female respondents’ attitudes around masculinity and traditional female gender norms.

Gender norms measure development

The study team used exploratory factor analysis to understand whether different factors underlie the overall construct of gender norms. First, we included the baseline responses for all participants enrolled in 2017 and 2018 for the 23 items related to gender norms and attitudes captured in the survey. We employed principal component analysis with varimax rotation. All 23 items were kept because they had a factor loading of 0.5 or higher. We determined the number of factors to maintain by examining the scree plot and identifying the distinct characteristics of each factor. Our analysis revealed six unique factors. Four factors (Girls to Blame for Mistreatment, Hypermasculinity, Sexual Relationship Stereotypes, and Guys Take Responsibility) included three to seven items and were combined into scales. To create these scales, we calculated respondents’ mean value across the items if the respondent had at least 75 percent of the items.

Internal consistency for the scales was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha. All scales except one had an alpha of at least 0.7, which is considered the threshold for internal consistency. The Guys Take Responsibility scale had an alpha of 0.61, in part because it was a three-item scale, and Chronbach’s alpha is heavily influenced by the number of items. One factor, Homophobia, had two items, which were averaged; the last factor was a single item, “It is a girl’s responsibility to avoid getting pregnant.” This factor stood out as a unique construct and was left as a standalone measure.

The gender norm factors identified among Manhood 2.0 participants align with previous studies that ask some of the same questions to samples of young men. However, this sample was very narrow in terms of age, race/ethnicity, and geographic location. Future researchers would be advised to test these measures against their own samples.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 5U01DP006129, which is a partnership between the Office of Population Affairs (OPA), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Research and Demonstration Program, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Reproductive Health. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the OPA, HHS, or CDC. The authors would like to thank Elizabeth Miller and Ashley Hill of the University of Pittsburgh for their insights.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube