Lessons Learned from Virtual Early Care and Education Coaching During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted early care and education (ECE) programs across the country in many ways, including changes to enrollment, staffing, and daily operations. Many programs closed or transitioned to providing virtual learning and services in response to state guidance and mandates, especially in the early months of the pandemic. ECE coaches—who provide support, training, and assistance to providers and programs—have responded to these program changes by adjusting both the structure and content of their coaching services to meet programs’ evolving needs. These adjustments have included transitioning from in-person to virtual coaching and covering additional topics, such as identifying and accessing resources related to COVID-19 and developing health and safety processes.

This two-part brief series focuses on the key components of virtual coaching for the Detroit Early Learning Coaching Initiative (DELCI). The first brief presented an overview of the DELCI coaching model and how it was adapted during COVID-19, including the transition to a virtual format. This second brief describes the key activities and components of virtual coaching used in DELCI and highlights lessons learned that may be informative for others interested in the provision of virtual coaching.

Download

Methodology

In May 2019, Child Trends contracted with the Early Childhood Investment Corporation (ECIC) to evaluate DELCI. Evaluation activities included a literature scan focused on coaching and professional development in ECE settings, interviews and focus groups with DELCI coaches and program staff, observations of DELCI coaches working with participants (in-person and via video), online surveys taken by DELCI participants, analyses of administrative data from ECIC, and meetings with stakeholders and community members in Detroit. The findings in this brief draw on DELCI coach and program staff interviews and focus groups as well as coaching observations.

Overview of DELCI

Through funding support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation as part of the Hope Starts Here Initiative, DELCI was launched in 2018 with two primary goals: 1) to improve the quality of ECE programs in Detroit; and 2) to engage ECE providers in Great Start to Quality (GSQ)—Michigan’s quality rating and improvement system. At the outset, DELCI was especially focused on recruiting both center- and home-based programs who had lower quality ratings (e.g., 3-Star and below) or programs who were not currently participating in GSQ.[1]

The main levers of change for the DELCI approach include 1) instructional coaching for teachers and providers; and 2) state-approved curriculum and assessment resources for programs. For DELCI, these supports are viewed as a way to support positive teaching practices and, as an extension, strengthen program quality and child outcomes.

DELCI coaching

Coaching before COVID-19

The DELCI approach draws heavily on the locally developed Early Educators Excel Coach-Based Adaptive Learning model (E3), which emphasizes goal-focused, individualized, data-informed, and practice-based coaching. DELCI coaches do not use a set curriculum, but instead draw on specific strategies from the E3 model to guide their work with participants. During in-person coaching sessions before COVID-19, this work included “on-stage” or in-context strategies (e.g., modeling, side-by-side coaching, in-the-moment feedback) and “off-stage” supports (e.g., following up via email, phone, or text to share resources or check in). As of March 2020, DELCI had recruited and provided instructional coaching to 84 programs (48% center-based, 52% home-based). This coaching was delivered primarily to ECE center-based lead and assistant teachers (referred to as teachers) and home- and group-based child care providers (referred to as providers)[2].

Coaching during COVID-19

As a result of COVID-19, all in-person coaching activities were put on hold in early 2020 and DELCI began the transition to virtual coaching. The current DELCI coaching model, which was adapted and revised during this transition, utilizes techniques that are both similar and dissimilar to the in-person DELCI coaching approach.[3] Since June 2020, about 65 teachers and providers have participated in virtual coaching. However, only about 15 are actively receiving instructional coaching, which includes the use of video-taped interactions between teachers, providers, and children and feedback on these interactions from coaches.

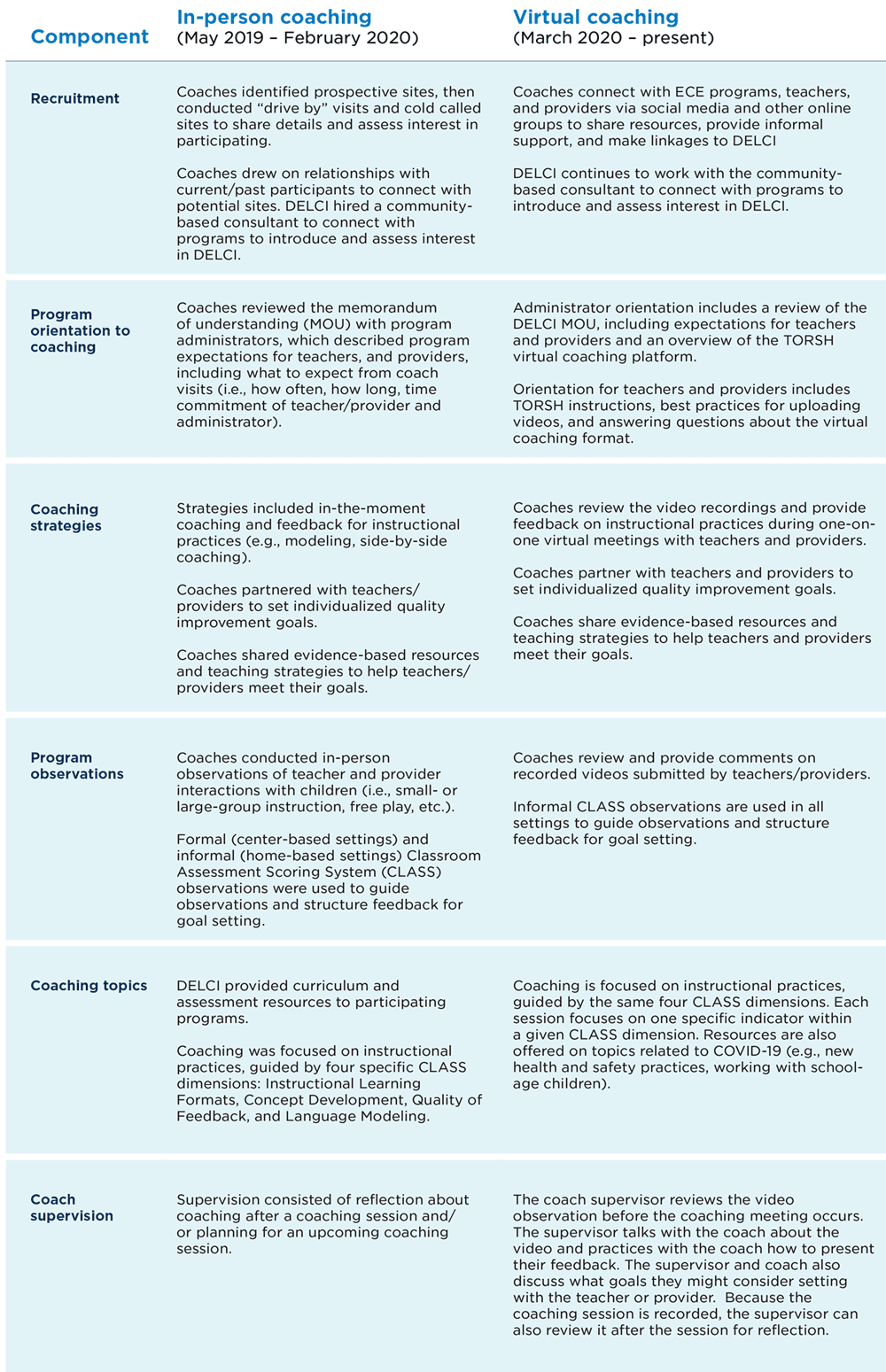

While the goals of virtual coaching remain the same as in-person coaching, the key activities and components used in virtual coaching have become more focused, and in some cases have changed. They include:

- Recruitment of teachers and providers into virtual coaching

- Training for coaches, teachers, and providers on how to utilize TORSH, a virtual coaching platform

- Recorded observations of teacher and provider interactions with children

- One-on-one meetings between coaches, teachers, and providers to review teacher, provider, and child interactions and to set quality improvement goals

- Supervision focused on the provision of virtual coaching strategies

Lessons Learned

DELCI coaches continue to engage with teachers and providers online, and it appears that virtual coaching will remain in place until the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. As coaches become more comfortable and skilled with the provision of virtual coaching, it will be useful for DELCI, and the field in general, to learn about how virtual coaching activities and components were received. This section presents specifics about the implementation of the key activities and components used in DELCI during the COVID-19 pandemic and uses them as a framework to highlight lessons learned regarding the provision of virtual coaching.

Recruitment of teachers and providers

DELCI is unique from many coaching models in that coaches are tasked with recruiting teachers and providers into the initiative. DELCI administrators and a community-based ECE consultant also assist with recruitment efforts. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, coaches used lists of ECE settings to identify eligible sites to contact regarding DELCI participation. Once sites were identified, coaches often made face-to-face-visits, talking directly with program administrators to assess and drum up interest in the initiative. Coaches also leveraged existing relationships with administrators, teachers, and providers who participated in DELCI previously and built on these connections to connect with new programs who might be open to participation.

Recruitment into DELCI during the COVID-19 pandemic has been challenging. Coaches cited the fact that many ECE programs are still being negatively affected by the pandemic as the primary reason for the lack of interest in DELCI participation. Challenges include sites not being able to find or retain staff, low enrollment numbers, changing classifications in order to care for more children, extending business hours, and taking on school-aged children in an effort to stay in business. These issues have challenged program operations and hampered administrator, teacher, and provider interest in and capacity for focusing on quality improvement efforts. One coach shared that a former coaching participant informed her, “This is my business, my livelihood. I’m trying to open back up and I don’t care about coaching right now.”

Since the pandemic, coaches have had to recalibrate their recruitment activities and strategies to account for the inability to connect with programs face-to-face. Current efforts have included the creation of peer-to-peer learning forums on social media sites, such as Facebook, to provide opportunities for teachers and providers to network and share common concerns and challenges. These exchanges also provide a forum for coaches to share resources and professional development supports, enabling opportunities for coaches to build trust with teachers and providers that may eventually lead to DELCI enrollment. In addition to social media, DELCI has also continued the pre-pandemic strategy of contracting teacher and provider recruitment out to a stakeholder who is well-known and highly trusted in the Detroit early childhood community. This individual identifies and contacts ECE programs and shares the benefits of the initiative to encourage participation.

Training for coaches, teachers, and providers specific to virtual activities

When it became clear that coaches would no longer be able to provide in-person instructional coaching, they reported being both worried and curious about what supports they would need, along with teachers and providers, to successfully engage in virtual coaching.

TORSH, an online coaching platform, was integrated into the coaching process and helped to reshape how interactions and conversations with teachers and providers were undertaken. One of the primary concerns expressed by coaches was how to adequately engage or develop rapport with teachers and providers without being able to meet in person. TORSH allows coaches to watch, pause, and add comments to video observations, as well as store notes, lesson plans, and other documentation in one place. TORSH also interfaces with Zoom, which allows the use of a split screen so teachers and providers can meet “face-to-face” with coaches to watch videos together.

Unfortunately, online platforms to support ECE coaching are not readily available “off the shelf” and may need to be adapted to facilitate ECE coaching. While coaches reported that TORSH could be integrated into the coaching process, a variety of online platforms were reviewed and assessed before TORSH was selected and purchased. The process of selecting a platform included pilot testing of TORSH by coaches and the coach supervisor, and collaboration with TORSH representatives to customize the platform so that it fit the needs of the initiative.

Once selected, coaches, teachers, and providers were trained by a TORSH representative on how to navigate the platform. Coaches were the first to be trained on TORSH and then teachers and providers followed. As coaching continued, it became evident that teachers and providers needed additional training, so coaches adapted information from a one-hour training created by TORSH to make the content more digestible for them. Specifically, teachers and providers needed training on how to set up their accounts, log in, and upload comments and video recordings.

Coaches interviewed noted there was no clear profile of a teacher or provider who might need support with virtual coaching. One coach expressed surprise that younger teachers and providers, who she typically thought of as tech-savvy, needed a fair amount of support to set up and navigate the TORSH technology, including support with uploading videos and joining Zoom meetings. She mused that these issues occurred in part because younger participants were used to “doing everything on their phone.”

Video observations

Video recordings are the primary tool utilized to shed light on the interactions between teachers, providers, and children. These recorded observations allow coaches to track teachers’ and providers’ progress and skill development. Because the use of videos is new and there are so few teachers and providers currently participating in the process, there is not currently a large library of video content for coaches to review. However, the expectation is that by recording and assessing videos over time, coaches will be better able to support participants by showing them how and where they are doing well and have made improvements.

Some coaches expressed concern about the limited number of observations used to assess teacher and provider practices. While in-person coaching facilitated observations of teacher and provider practices for extended periods of time during a single visit, video recordings provide just a brief snapshot of interactions between teachers, providers, and children. Because coaches were often unable to understand the broader context of the interactions being recorded, they reported being concerned about using a single observation to assess teachers and providers. One coach shared that, prior to the pandemic, she would have simply “stopped by” a site to ensure she had a broad understanding of what was occurring in the learning settings.

With the initiation of virtual coaching, coaches are unable to do their jobs if teachers and providers do not tape and upload videos; coaches also noted that mastering videotaping logistics made participation in coaching more appealing. One coach explained, “TORSH isn’t wrong, coaching isn’t wrong…the taping and uploading…that’s hindering the process.” This coach also shared that once teachers and providers learn the videotaping process, participating in coaching is “easy.” The key is that “people need to first have success.” This includes understanding how to complete basic technological tasks, such as taking and uploading videos, as well as advanced tasks that require more training, such as understanding and being intentional about what types of interactions to record to ensure coaching is as useful as possible.

Interviews with coaches and coach supervisors also indicate that assessment tools, paired with the recorded observations, have helped facilitate successful virtual coaching. Like the in-person coaching process, coaches use the CLASS tool[4] to conduct teacher and provider observations and individualize the coaching process. Coaches emphasized that CLASS provides a flexible framework for initiating and launching conversations, while also helping them work in a personalized way to identify what matters most to coaching participants. For example, after each coaching session, coaches complete a coaching log, which is connected to a CLASS indicator that identifies where a teacher or provider falls on a 1-7 scale. Utilization of the scale provides a way for coaches to see and document change on the specific area that they are working on with teachers and providers, such as their use of open-ended questions. CLASS is used to ground virtual coaching in a structured way, by ensuring that coaches, teachers, and providers have and adhere to areas of growth that have been proactively and collaboratively identified.

One-on-one meetings with goal setting

Coaches have noted that the development of positive relationships between teachers and providers remains a top priority during virtual coaching. Relationship building is a cornerstone of DELCI coaching and has been accomplished in large part through online, one-on-one meetings between coaches, teachers, and providers.

Coaches have expressed, however, a need to use more intentional strategies related to relationship building, particularly for new teachers and providers with whom they lack preexisting relationships and have never met in person. One coach shared that “miscommunication” happens easily and it “takes more time to get to…trust [and] honesty” when virtual meetings are the only option. Strategies coaches use to overcome this barrier include hosting introductory meetings that include “walk throughs” of settings, where a teacher or provider uses their camera to show learning stations, books, supplies, and other items. These meetings enable coaches to see the physical spaces that teachers and providers use. One coach described meetings that were held with teachers and providers in advance of the formal coaching process. She stated, “we had pre-coaching sessions with providers who were ready…[we] discussed what would be videotaped, how they felt about it, goals we would set together… [we] had a deep discussion about how it would look.” Strategies like this help facilitate relationship building and comfort with the video observation process.

Additional strategies to address teachers’ and providers’ comfort with being observed during virtual coaching include showing patience and empathy about issues that some teachers and providers were initially reluctant to share. For example, some participants are less comfortable with virtual technology, are concerned about how they look or sound on video or are worried about having the skills to effectively manage changes and new dynamics in their settings (e.g., taking on new roles because there were less staff available and working with children of different ages in the same classroom[5]). Coach strategies to alleviate anxieties like these include acknowledging that working virtually comes with challenges, recognizing that teachers and providers were not expected to be prepared for every unanticipated change, spending time with teachers and providers to practice using the technology, collaboratively developing expectations about when videos should be to be uploaded and what they should include, and setting a tone for coaching that included grace and humor. In addition, for teachers and providers who were not fully comfortable or ready to have observations completed, coaches still worked to develop and maintain relationships with them, as well as to provide information, referrals, and professional resources.

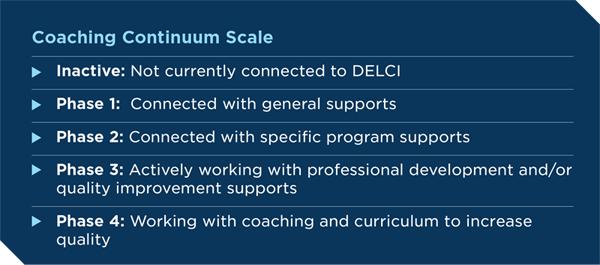

Prior to the initiation of virtual coaching, teachers and providers were identified as either “prospective” meaning coaches were not working directly with them in the learning setting or “active” meaning coaches were in classrooms and homes working directly with teachers and providers one-on-one. When virtual coaching began, participants were initially categorized on a continuum from 1-4, and coaching support was provided based on teacher and provider requests and identified needs. Currently, new programs are automatically categorized as a 4 because they are being recruited and specifically signed up for virtual coaching, eliminating the need for them to move along the continuum.

The main steps of virtual coaching (Phase 4) include: teachers and providers recording and uploading a video observation to the TORSH platform; coaches independently reviewing and preparing feedback and discussion topics related to the video recordings; and coaches, providers, and teachers participating in a virtual coaching session. During the virtual coaching session, the coach encourages the teacher or provider to reflect on their instructional practices, and shares their feedback on the video. The coach and teacher or provider then set goals, using the CLASS dimensions as a guideline. Teachers and providers can also upload an “artifact” to TORSH for the coach to review, such as a lesson plan or notes.

The schedule for virtual coaching is more reliant on teachers and providers. While the DELCI coaching model is structured and follows a set format, the schedule for virtual coaching differs from face-to-face coaching where coaching interactions were initiated by the coach. With virtual coaching, opportunities for coaching are heavily dependent on how often a teacher or provider uploads a recording. For this reason, the timing of observations or coaching sessions may not be as consistent as when coaching was provided in-person.

Despite these changes, coaches have indicated that the shift to virtual coaching allows for deeper exploration and understanding of topics and more active participation by teachers and providers in the process of coaching. In person, teachers and providers were navigating various activities and monitoring children. This left very little uninterrupted time for reflection and debriefing. In the virtual context, coaches, teachers, and providers meet when it is convenient for them and conversations can be had with minimal interruptions and more depth. In addition, coaches are not able to “take over” interactions between children and teachers or providers, which coaches indicate has resulted in more active utilization and implementation of instructional strategies. Coaches also report that teachers and providers are more open to strengthening their skills. This openness comes in part because teachers and providers feel that video footage is a more objective and unbiased account of their interactions with children than coach feedback, which could be subject to interpretation based on a coach’s viewpoint or lens.

Supervision

With the shift to online coaching, DELCI coaches need to be well-versed in instructional coaching and understand how to transfer that knowledge in a virtual space. Supervision was reported by coaches to be particularly helpful with strengthening this skill. As mentioned previously, a key change in the switch from in-person to virtual coaching is the inability to hold more fluid or natural conversations with teachers and providers in the moment. Coaches are now responsible for creating the conditions for conversations to occur. Notably, both coaches and supervisors have shared that the issue is more about the lack of familiarity with facilitating online conversations than the virtual environment itself. Regular supervision–both individually and in groups–has been key to meeting this challenge.[6].

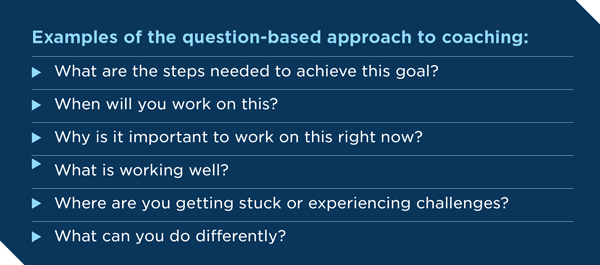

In recognition that virtual conversations differ from in person ones, supervision focuses more on developing coaches’ inquiry skills and learning how to ask more open-ended questions to facilitate better understanding about what is happening with teachers and providers. Moving toward a question-based approach to coaching puts teachers and providers in control of their work. This approach facilitates the sharing of experiences that enables teachers and providers to fully engage in and own the solution process (see Table 2 for a list of questions used by coaches). The coaching team also mentioned that similar questions were often used between coaches and DELCI supervisors, with the end result being that the supervisors’ work with the coaches mirrors the coaching that occurs with the teachers and providers—in essence, “a parallel process.”

Source: Detroit Early Learning Coaching Initiative, 2021

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on ECE settings, and coaching has not been immune to these changes. Over the course of the past year, DELCI coaches and supervisors have incorporated and experimented with new platforms, coaching, and supervision strategies, and are continuing to innovate and discover what works best for teachers, providers, and coaches. Other stakeholders involved in or considering a switch to virtual coaching can use the considerations and lessons learned in this brief and apply them to their own contexts. These insights can help strengthen the skills and capacity of ECE teachers and providers so they are better able to support children’s growth and development.

Notes

[1] All licensed programs and providers in Michigan are part of Great Start to Quality. Programs who choose to participate in the GSQ rating process are rated on a one- to five-star scale. Licensed programs and providers who do not participate in the rating process still have a profile in the GSQ system and appear as an Empty Star.

[2] In Michigan, a licensed home-based provider can care for a maximum of six children. A group provider can care for up to 12 children but must have an assistant if there are more than six children or more than two infants and/or four toddlers.

[3] A detailed description of the transition to virtual coaching in DELCI, as well as an overview of what coaching looked like during the initial months can be found in the first brief in this series.

[4] The CLASS tool measures the quality of teacher-child interactions and is correlated to educational outcomes for preschool age children. CLASS has not been designed for use in home-based settings.

[5] With the closure of many K-12 schools due to COVID-19 (and the subsequent shift to remote learning), many child care programs expanded their enrollment to include school age children.

[6] In DELCI, individual supervision entails a single supervisor interacting with a single coach to focus on coach, teacher, and provider concerns. Group supervision includes more than one coach and uses the power of the group to brainstorm, problem solve, and provide support to each other about coaching activities.

Download

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube