The Evolution of State School Safety Laws Since the Columbine School Shooting

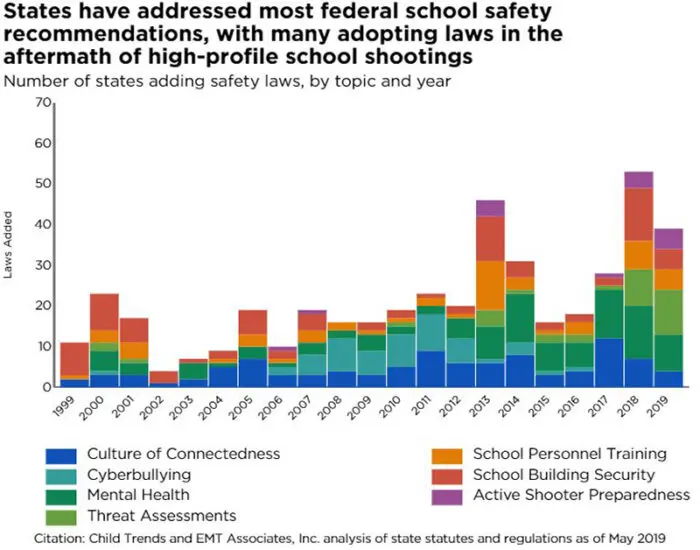

The 1999 shooting at Columbine High School was a watershed moment for many state lawmakers working to keep schools safe. In response to that school shooting—and several other high-profile shootings over the next two decades—policymakers passed new statutes and enacted new regulations in hopes of stopping similar incidents. Unfortunately, as this report reveals, most school safety laws passed after high-profile school shooting incidents primarily focus on preparing for, not preventing, such events. Although many states have incorporated strategies associated with violence prevention into their policies, such as those related to school climate or social and emotional learning, these laws were largely not connected to school shooting incidents.

This report explores how seven topics identified by the Federal School Safety Commission (FSSC) in its December 2018 final report have emerged in state statutes and regulations (including those from Washington, DC) over the past 20 years.1 The federal departments of Education (ED), Health and Human Services (HHS), Justice (DOJ), and Homeland Security convened the FSSC after the 2018 Parkland, Florida, school shooting to identify “best practices” to prevent future school shootings.

The FSSC’s final report examined the relationship between school shootings and 19 issue areas. While many of these issues extend beyond the role of schools—such as press coverage of mass shootings or federal governance—the seven topics addressed in this report have direct implications for school practice and the state laws that govern such efforts:

- Character development and culture of connectedness

- Cyberbullying

- Mental health and counseling

- Anonymous reporting systems and threat assessments

- School personnel training

- School building security

- Active shooter preparedness

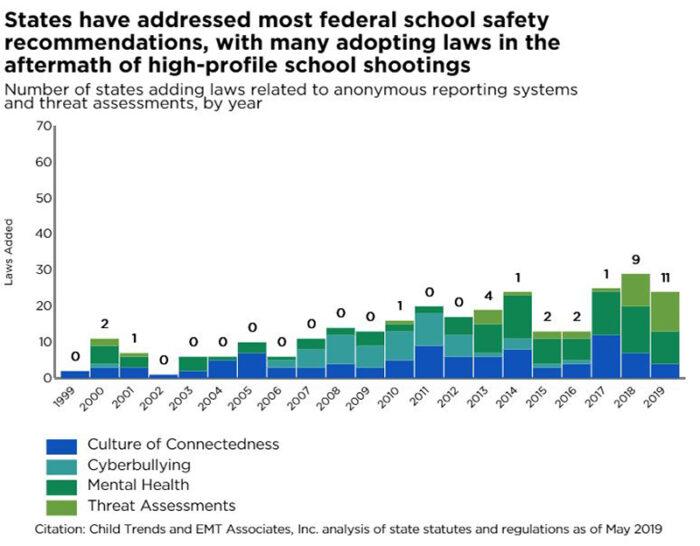

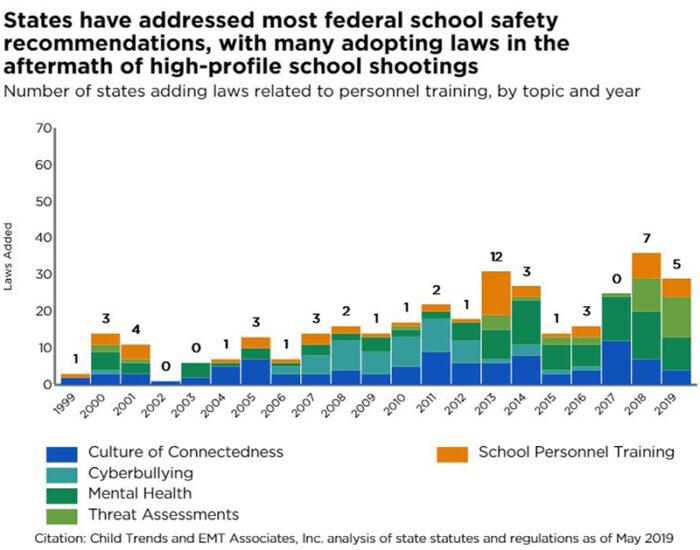

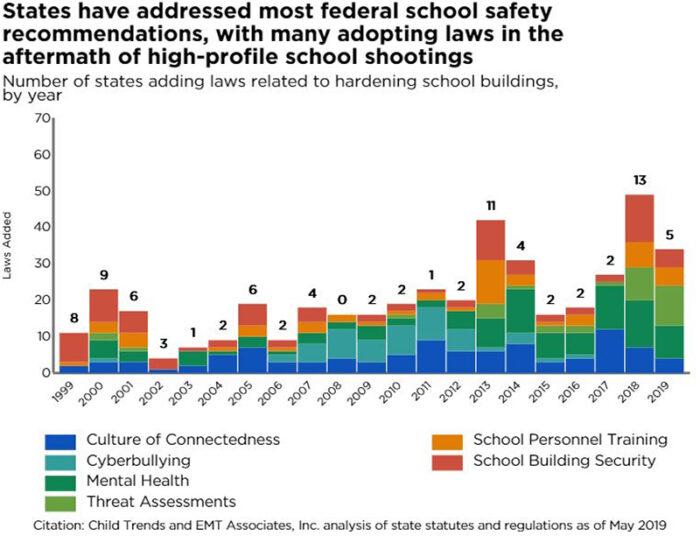

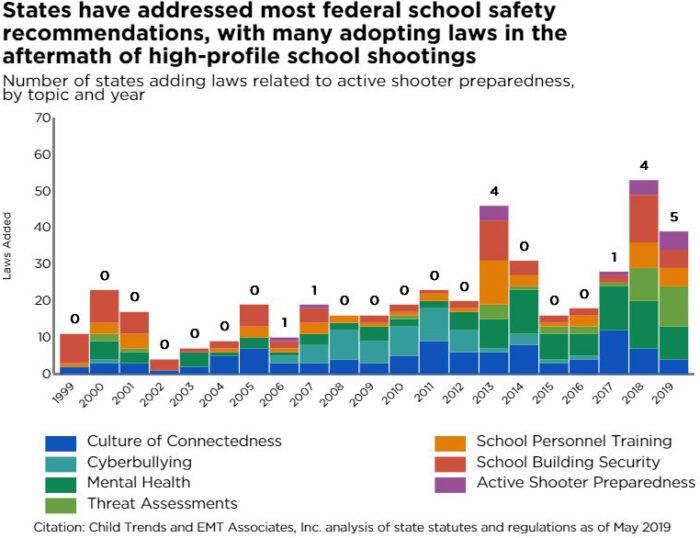

A closer analysis shows that policies aimed at preparing the school environment for an active shooter event (e.g., school hardening, active shooter drills) were enacted in the years immediately following major school shooting events.

State policymakers added the highest number of laws focused on preparatory strategies during the periods following the 2012 Sandy Hook and the 2018 Parkland shootings.

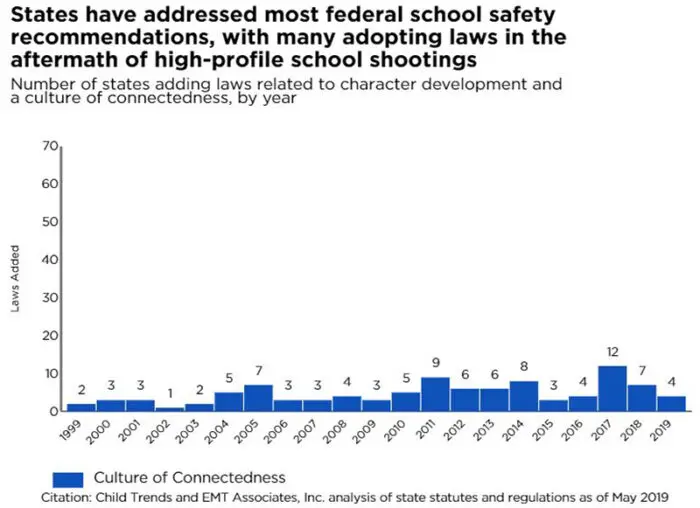

The state-level adoption of preventative laws (i.e., those focused on developing the individual skills and classroom environments that prevent school violence from occurring, such as character development) is more evenly dispersed across this 20-year period. In other words, laws aimed at preventing school shootings and violence are less likely to be connected to the occurrence of school shooting incidents. Notably, laws focused on mental health and counseling were primarily enacted after 2013, with gradual additions through 2019.

The following sections examine, in detail, which states have laws that address each of the seven topics, along with the year(s) in which states first added these provisions.

Character Development and Culture of Connectedness

The FSSC recommends that states better support schools to implement whole-school efforts that build positive school climates, support students’ character development and social-emotional learning, and implement multi-tiered systems of supports or positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS). The FSSC report notes that when students have deeper connections to school, violence is less likely to occur.2 Although a handful of states had laws addressing these prevention-focused efforts even before 1999, widespread adoption did not occur until after 2010. The adoption of these laws largely did not coincide with major school shooting incidents. Although the laws may refer to school safety, they often cite broader issues such as bullying and student mental health, rather than prevention of school shootings, in explaining their purpose.

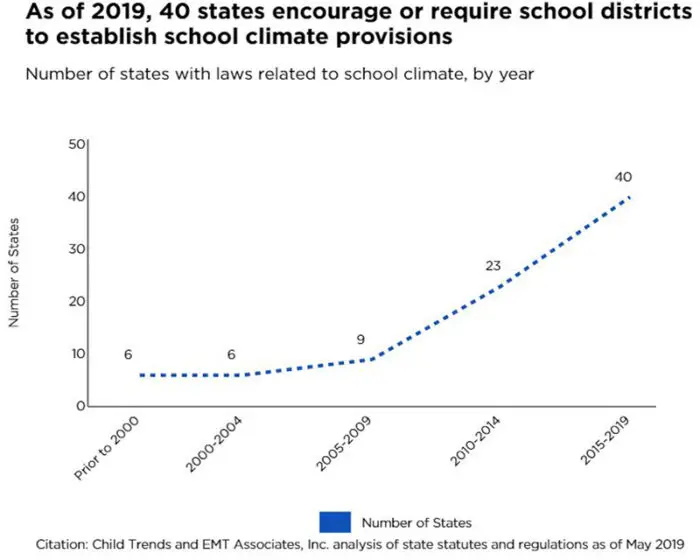

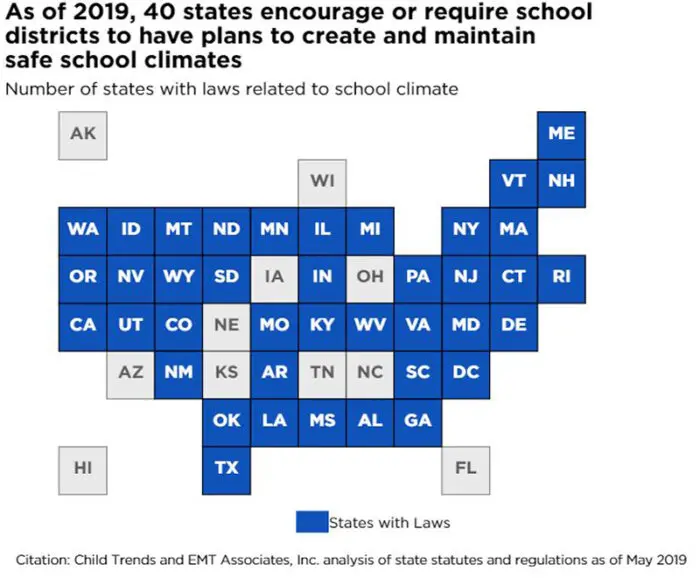

Laws addressing school climate typically require districts and schools to develop and implement plans to create and maintain safe and supportive conditions for learning. As of 2019, 40 states encourage or require school districts to establish school climate provisions. Most of these laws focus on developing school climate plans or implementing programs to support a positive school climate. However, laws in Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Louisiana, and Massachusetts encourage or require the collection of school climate survey data from students in at least some schools, and Georgia requires the creation of a ranking system for schools based on the quality of their climates.

California’s school counseling law, passed in 1987, is the earliest law that references improving school conditions for learning, followed by Georgia’s in 1991. The majority of states (21) added provisions referencing the concept of school climate after 2010. Seventeen of these states added laws addressing school climate from 2015 to 2019.

Helping students understand their own emotions, recognize how their actions impact others, and resolve conflicts and disagreements is critical to creating and maintaining safe schools.3 Character development and social and emotional learning are related, although not fully interchangeable, strategies for accomplishing these goals.4 States have long incorporated character development into their laws; more recently, some states have adopted language specific to social and emotional learning. We consider references to both character development and social and emotional learning (or specific components thereof) within state laws.

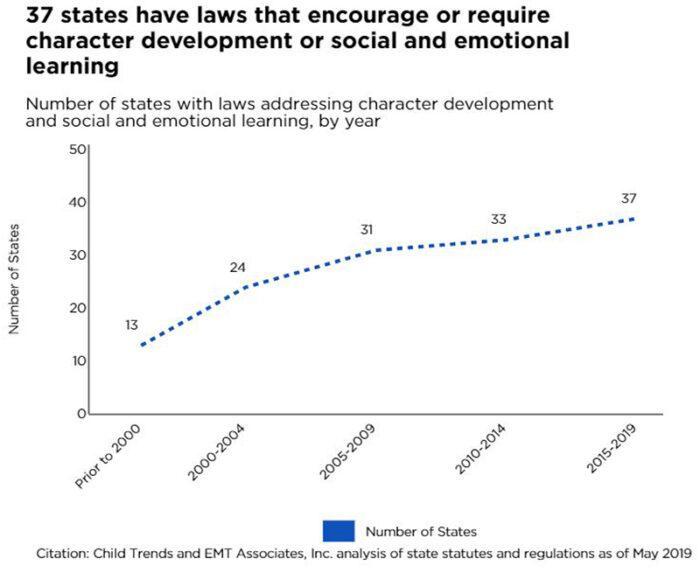

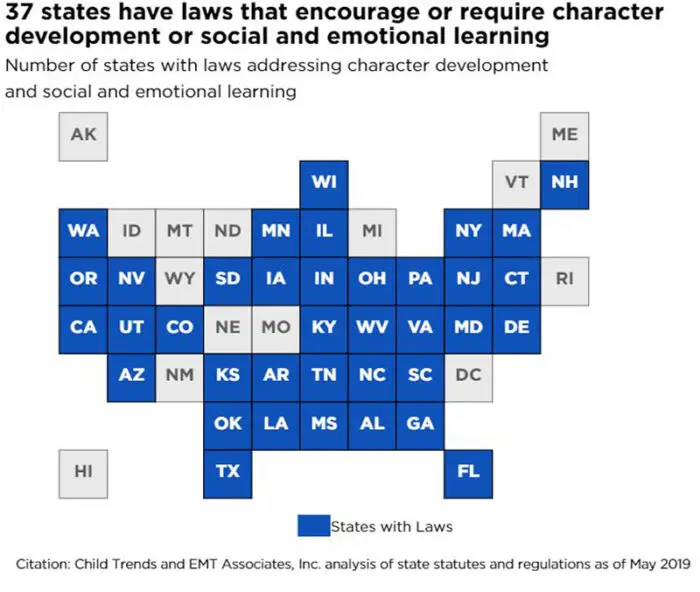

As of 2019, 37 states have laws that encourage or require schools to address character development or social and emotional learning.

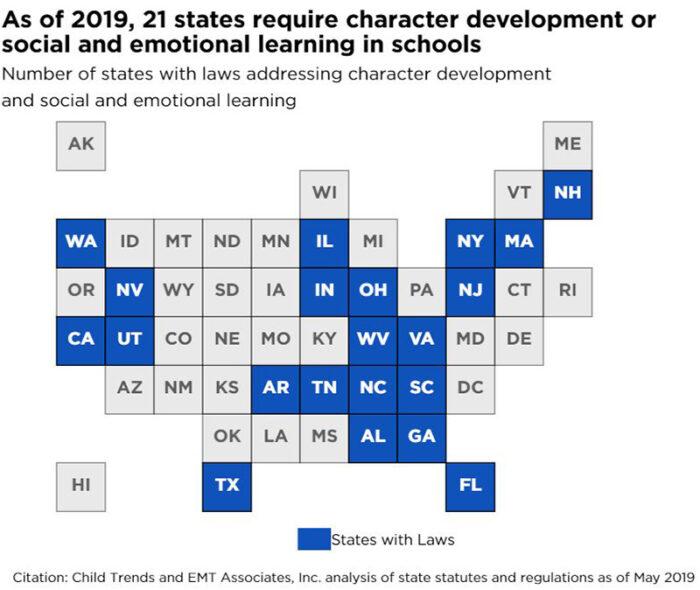

Twenty-one states specifically require districts to address these concepts in schools. Specific terminology varies considerably between states. Indiana, for example, references “good citizenship instruction,”5 while Maryland embeds social and emotional learning under its definition of “restorative approaches” in relation to student discipline.6 Texas does not specifically reference character development or social emotional learning, but instead requires instruction in “mental health, including instruction about … skills to manage emotions, establishing and maintaining positive relationships, and responsible decision-making …”.7

Tennessee passed the first law requiring character education in 1985, and nearly half of all states (24) had laws by 2004. From 2017 to 2019, only four new states (Arkansas, Maryland, North Carolina, and Washington) added laws addressing character education or social emotional learning.

Multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) use a data-based process to identify and provide supports to students.8 The system is a three-tiered framework, whereby all students receive supports in the broadest tier, while supports are more tailored for students with greater need in the second and third tiers. MTSS can be used to address a number of needs, including both academic and behavioral challenges. Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Response-to-Intervention (RTI) are both considered types of MTSS.

As described in the FSSC report, MTSS designed to address student behavioral challenges can help prevent school violence; used systematically, MTSS can reduce disciplinary referrals and improve overall perceptions of school safety9. For this analysis, we focus on state laws that reference MTSS to address student behavior school-wide. Although many states specifically reference PBIS, or reference adaptations of RTI to focus on behavior, others provide more general descriptions of behavioral support with components consistent with MTSS (i.e., addressing behavior from both universal and more targeted levels in the context of a cohesive framework). This analysis excluded state policies that referenced behavioral supports without mention of a tiered framework—for example, special education laws regarding positive behavioral supports for individual students with disabilities.

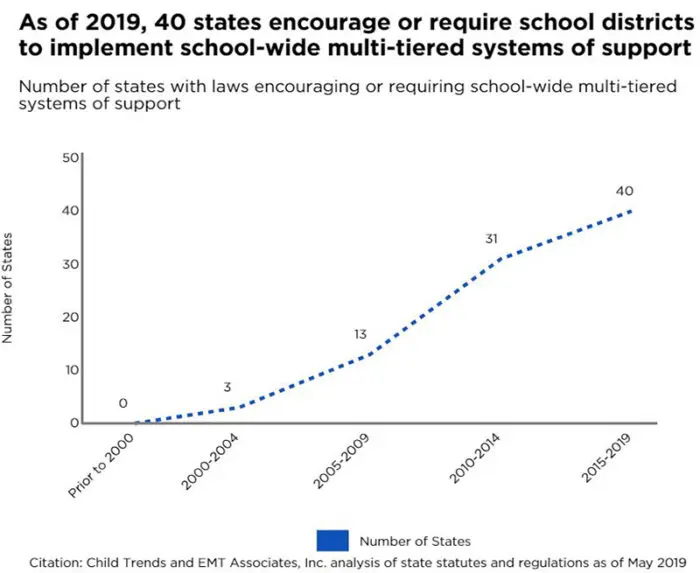

As of 2019, 40 states encourage or require districts to implement MTSS for behavior, with 20 states requiring its use. Maryland was the first state to reference MTSS in law in 2002, followed by Louisiana in 2003 and New Hampshire in 2005. States gradually added laws related to MTSS over the following decade, with eight states adding laws from 2005 to 2009, 18 states from 2010 to 2014, and nine from 2015 to 2019.

Cyberbullying

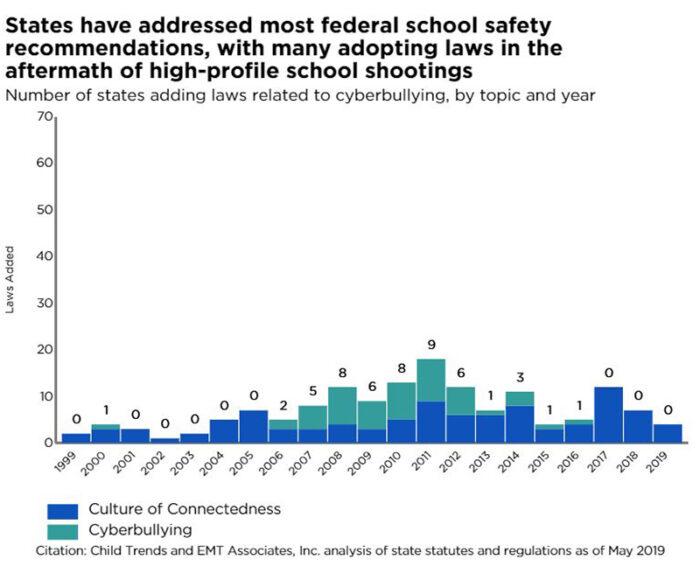

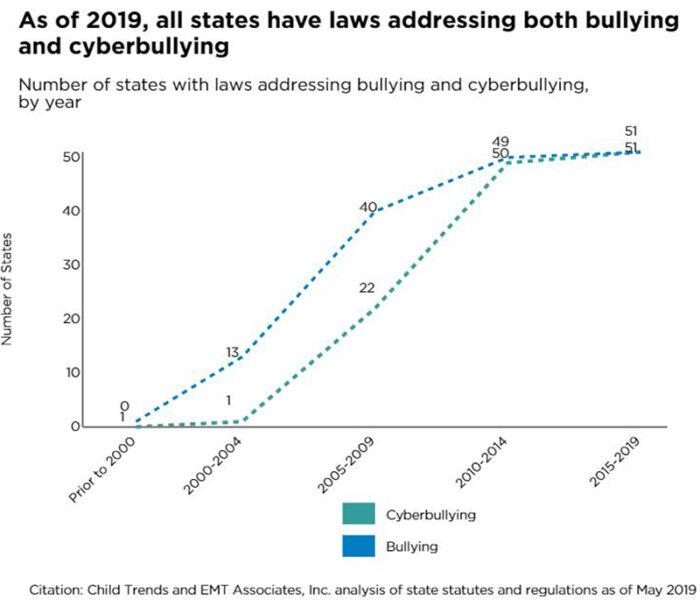

Following the 1999 Columbine shooting, six states enacted legislation requiring districts and schools to address bullying, with 13 states passing legislation by 2009.10 This reaction was partly in response to a pervasive narrative that bullying was a predominant precipitating factor for the perpetrators at Columbine and other school shooting incidents, although the role of bullying in these incidents remains a source of debate.11 By the time of the 2018 school shooting in Parkland, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had existing laws addressing bullying in schools.

The FSSC report highlighted a subset of bullying behaviors—cyberbullying—as a key issue to be addressed. Overall, state policymakers have largely focused on cyberbullying as an issue affecting students’ mental health and suicidality, rather than a precipitating factor for broader school safety issues. Policy making around cyberbullying has therefore not clustered around known school shooting incidents; rather, it clustered in a period from 2008 to 2012. By 2016, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had laws addressing cyberbullying on school campuses, and 30 states address cyberbullying that occurs off-campus.

Colorado was the first state to reference cyberbullying in its bullying laws in 2000, followed by Idaho and South Carolina in 2006. All three states included references to cyberbullying in their original bullying laws. The last state to add references to cyberbullying was California, in 2016, although California’s original bullying law dates to 2007.

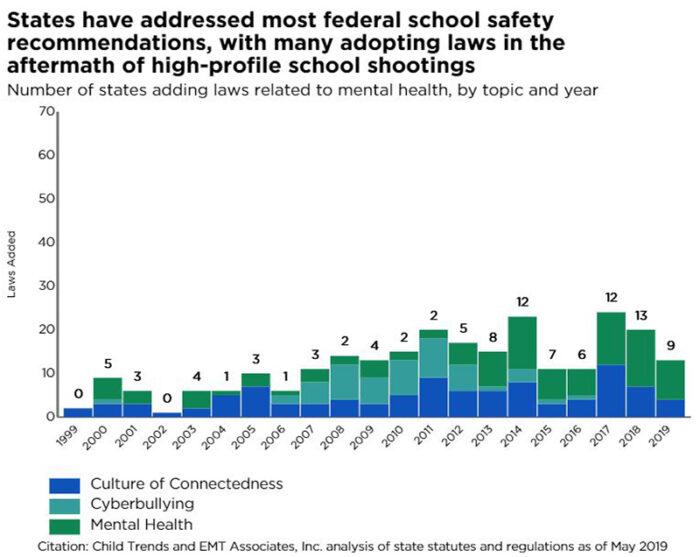

Mental Health and Counseling

The FSSC report highlights what previous Child Trends work has confirmed12 —that there is little association between having a diagnosed mental health illness and committing violence. Indeed, children with mental health needs are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators.13 However, the FSSC report highlights the need to expand comprehensive mental health services for students in order to enhance protective factors that buffer the effects of violence, reduce other risk factors that may contribute to violence perpetration, and improve schools’ ability to respond to violence. The report specifically calls on states to improve mental health identification and referral procedures, improve access to comprehensive school-based mental health programs, and train school staff to effectively respond to their students’ mental health needs.

Although some states began incorporating school-based mental health services into laws prior to 2000, most laws pertaining to these services were enacted after 2012. Since then, such laws have been more directly tied to school safety efforts, both in terms of their content and their placement within state education codes.

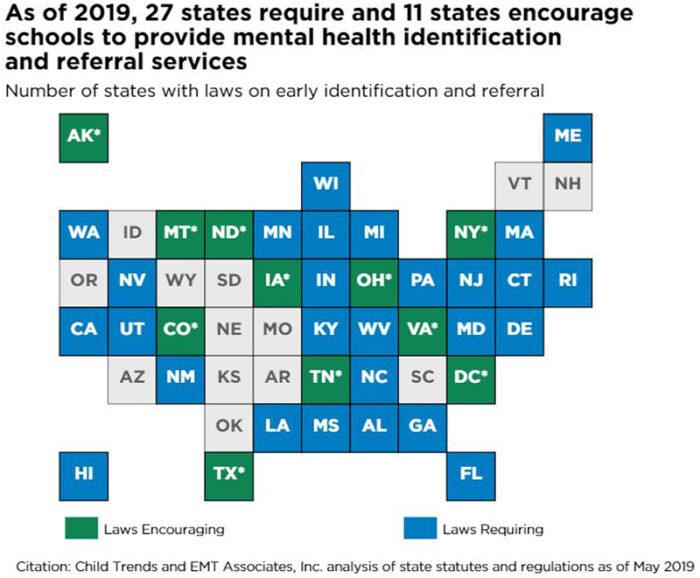

Schools can serve as key intermediaries in identifying children who need mental health services and in providing resources and references to families to receive those services. As of 2019, 11 states encourage—and 27 require—districts and schools to provide mental health identification and referral services.

Laws in Hawaii (1988), Connecticut (1990), and California (1991) included the earliest references to mental health referrals by schools; each of these states subsequently amended and updated their laws. Most states (24) enacted laws regarding mental health identification and referrals after 2010, with seven laws passed from 2018 to 2019.

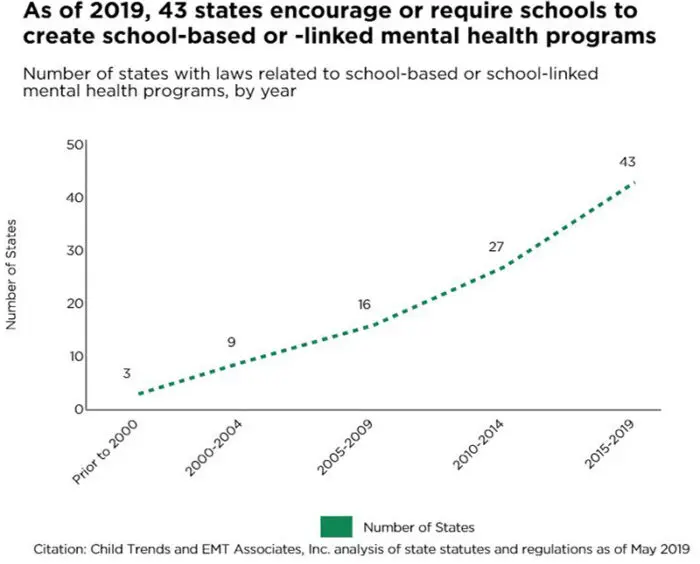

School-based or school-linked mental health programs can promote access and reduce stigma associated with using such services.14 Twenty-eight states encourage schools to create school-based or school-linked mental health programs, and an additional 15 require it. In some cases, mental health programs are embedded within school safety plans. For example, South Carolina’s law establishes a school safety task force to “… develop standards for district level policies to promote effective … mental health intervention services.”15 Tennessee’s law similarly embeds comprehensive school counseling and mental health programs within the purview of a state-level safety team.16 Other states, such as Colorado, embed mental health programs within the scope of school-based health centers.

Laws in Connecticut (1990), Hawaii (1991), and Idaho (1997) include the earliest references to school-based mental health programs. Most states (27) added such references to their laws after 2012, with seven states enacting laws in 2018 and 2019.

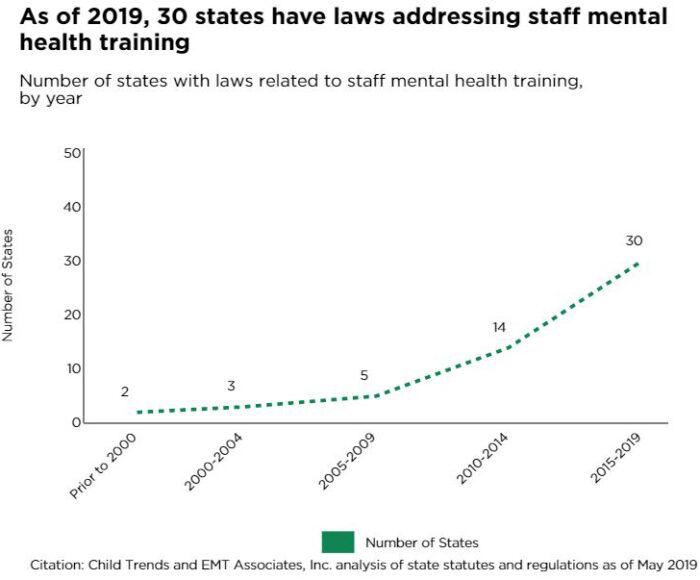

To better address their students’ needs, schools can provide teachers and other school staff with basic training, such as Mental Health First Aid, upon the signs of—and in response to—mental distress.17 As of 2019, 30 states’ laws address staff mental health training, and seven specifically reference Mental Health First Aid.

Twelve states directly link staff mental health training to school safety efforts. For example, Michigan lists training for teachers on mental health as an essential component of emergency operations plans,18 and Georgia includes mental health among the training topics contained within its required school safety plans.19

Hawaii has the earliest law referencing mental health training for staff, enacted in 1974, followed by Tennessee in 1994. Six states passed laws on staff mental health training from 2003 to 2012. The remaining 22 laws were passed after 2013, with eight enacted after 2018.

Threat Assessments

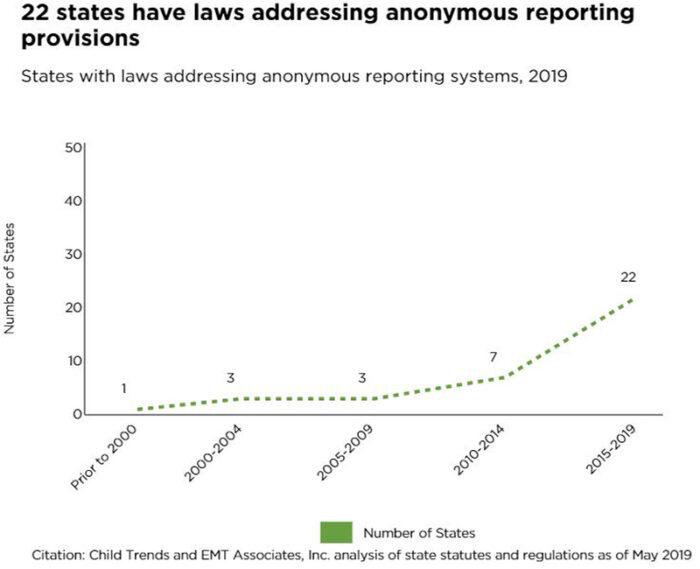

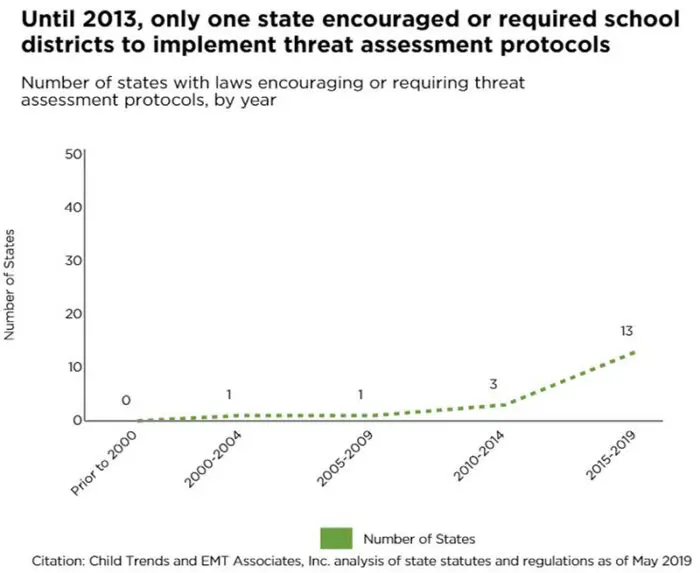

Both the FSSC report and a subsequent U.S. Secret Service analysis20 highlight that, in most school shooting incidents, perpetrators made their intentions known. Mechanisms to both receive information about potential threats and systematically assess and respond to those threats can help prevent shootings. Laws addressing anonymous reporting systems and threat assessments in schools are relatively new, with the vast majority enacted after 2013.

Anonymous reporting systems can include phone lines, text systems, and/or email boxes that allow for communication of potential threats to school systems and law enforcement. As of 2019, 22 states address or establish provisions for anonymous reporting systems related to school violence concerns.

Virginia established the first anonymous reporting system in its laws in 1993. Although not required, the law encourages school systems to partner with local law enforcement and news media outlets to establish a “school crime line.” New York (2000) and Rhode Island (2001) added similar lines shortly after the 1999 Columbine shooting. The remaining 19 states added laws pertaining to anonymous reporting systems from 2010 to 2019, with 10 states enacting laws in 2018 and 2019.

Threat assessment is a concept originally developed by the U.S. Secret Service that is now being applied in school settings. The process typically involves a multidisciplinary team—including law enforcement, educators, and mental health providers—working collaboratively to identify students who have threatened or are at risk for violence, assess the seriousness of the threat, and develop an intervention approach that addresses underlying problems contributing to the threatening behavior.21

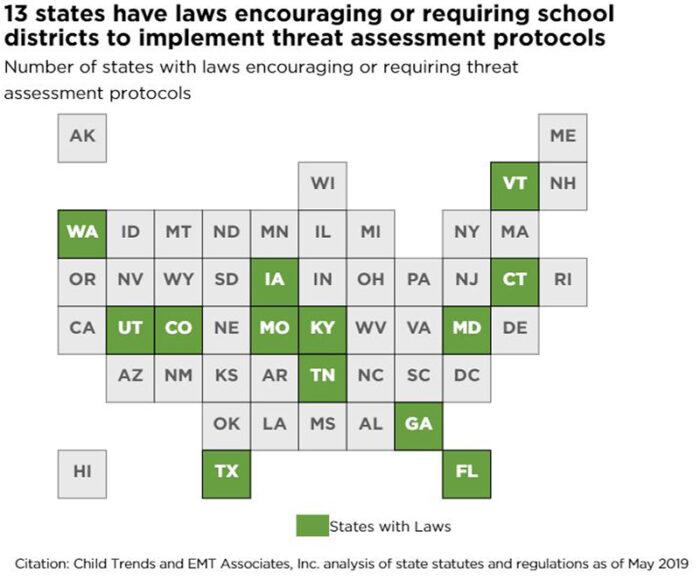

Thirteen states have enacted laws that encourage or require school districts to implement formal threat assessment protocols. Of these, eight states encourage or require districts to adopt formal school board policies detailing threat assessment protocols. Five states mandate the development of state model policies or guidelines to advise districts on implementation, and three require state education agencies or districts to provide threat assessment training for school personnel.

The first state threat assessment law was passed in Virginia in 2000, requiring the Virginia Center for School Safety to provide technical assistance to districts to support safety planning efforts. These technical assistance efforts were to include the development of protocols addressing threat assessment in schools.22 The second state to implement a formal threat assessment law was Indiana, in 2013, followed by 10 other states in 2018 and 2019. Several states, including Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Washington, had existing provisions in state laws that served as precursors to more formal threat assessment protocols. For example, Connecticut mandated that Safe School Climate Committees “collect and evaluate information on instances of disturbing and threatening behavior” and report information to the Safe School Climate Coordinator. Similarly, Washington required districts to establish a plan to recognize, screen, and respond to emotional or behavioral distress in students.23

As states strengthen school surveillance and enforcement activities, many have also balanced the need to ensure equity in the school environment and protect students from biases that could influence the results of threat assessment procedures. For example, Texas’ 2019 threat assessment law mandates training for threat assessment team members on avoiding bias when identifying students at risk. Similarly, the most recent amendment to the Maryland Safe to Learn Act requires the state to develop a model policy for schools to include formal training for threat assessment team members on “implicit bias and disability and diversity awareness with specific attention to racial and ethnic disparities.”24

School Personnel Training

The FSSC report calls for training all school staff on emergency operations and school safety procedures, but also for specialized training of school-based law enforcement (or school resource officers; SROs). The FSSC further recommends the establishment of memoranda of understanding (MOUs) between law enforcement and school systems about the role of SROs in schools.

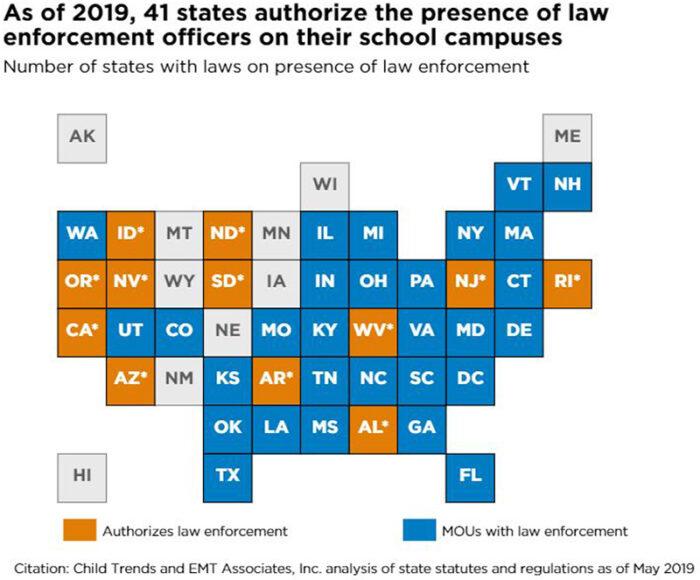

Schools often partner with local law enforcement agencies to provide security personnel on campus (such as SROs) to be available if an emergency occurs. According to national data from the 2015-2016 school year, about 42 percent of all public schools report having an SRO or other school security personnel present on school grounds for at least one week during the school year.25 However, little evidence suggests that increased policing of school campuses makes them any safer. According to a Congressional Research Service report, there is some evidence that the presence of SROs on campuses may increase law enforcement involvement in discipline for minor, nonviolent offences.26 This is of particular concern given demonstrated disparities in the use of discipline for such offenses for students of color.27 As noted in the FSSC report—and detailed in a 2016 guidance letter from ED regarding SROs on school campuses—MOUs are critical to establishing the role of SROs on campus, including their role in securing school facilities, and limiting their role in student discipline.

As of 2019, 41 states authorize the presence of law enforcement officers on their school campuses, of which 29 either encourage or require districts to establish MOUs with local law enforcement that clearly define the roles and responsibilities of officers in school settings. For example, a 2019 Washington law includes explicit restrictions on officer roles, stating that SROs should “focus on keeping students out of the criminal justice system when possible and should not be used to attempt to impose criminal sanctions in matters that are more appropriately handled within the educational system.”28 The Washington law, and others like it, underscore the tension between the need for increased policing and monitoring of school campuses to protect them from serious safety threats and the need to ensure an equitable school environment and limit the criminalization of minor student behaviors.

While some states, including Kansas, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Texas, enacted laws encouraging or requiring MOUs with law enforcement prior to 1999, most states enacted laws after 2012 (17 states). Eight states have added laws encouraging or requiring MOUs since 2016, after ED issued its guidance letter.

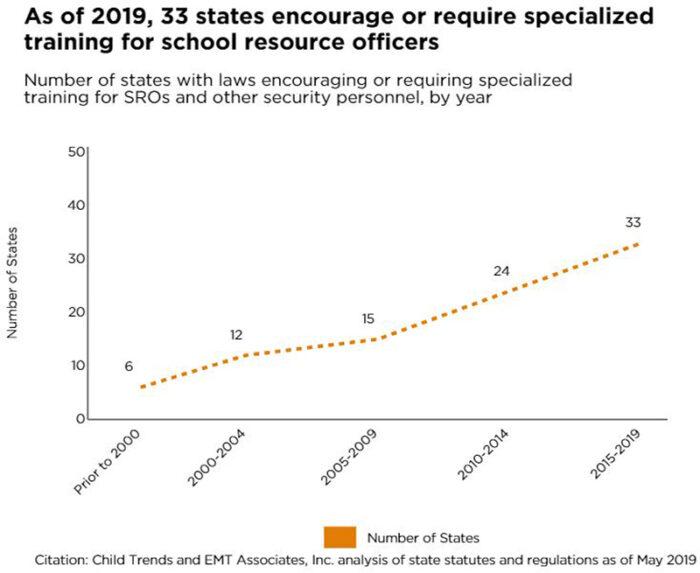

In tandem with MOUs, specialized training helps ensure that law enforcement personnel on school campuses are aware of issues specific to working with children and adolescents, including an awareness of child and adolescent development and other issues unique to the school environment. As of 2019, 33 states encourage or require specialized training for SROs and other school security personnel. Many recent laws go beyond security and enforcement in the physical school environment to embrace aspects of both social-emotional climate and protections for students with trauma or underlying mental health needs to ensure their safety and psychological well-being. For example, the 2019 Washington law that authorized the presence of SROs in schools also mandated comprehensive training on content areas that included—but were not limited to—child and adolescent development, trauma-informed approaches to working with youth, recognizing and responding to youth mental health issues, de-escalation techniques, and bias-free policing and cultural competency.29

Most states (18) with laws encouraging or requiring specialized training for SROs and other security personnel enacted them after 2012. Early adopters, including Connecticut (1993), Delaware (1991), Florida (1991), Rhode Island (2001), Texas (2001), and Virginia (2001), have all passed subsequent legislation to extend and expand the requirements for SRO training.

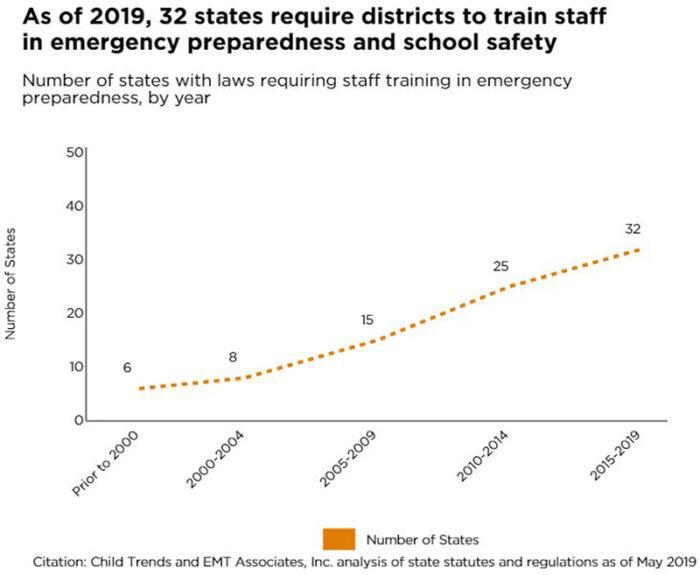

The FSSC clearly states that, even with an SRO present, all school staff should be prepared for a school security emergency. As of 2019, 32 states encourage or require districts to train staff in emergency preparedness and school safety. Many of these laws are not specific on the content required, but embed training requirements within broader school emergency planning. For example, Indiana simply requires that “safety and emergency training and educational opportunities for school employees” be included in school emergency operations plans,30 and Nebraska’s law tasks a state school security director with “[e]stablishing security awareness and preparedness tools and training programs for public school staff.”31 More recent laws specify requirements for staff active shooter preparedness (see section below).

States have added staff training provisions in clusters, with 14 adding training requirements since 2012. Four states added staff training provisions in 2007 and 2008, another seven added them in 2013 and 2014, and five added them in 2018 and 2019.

School Building Security

The FSSC report identified several “best practices” for securing the school building in the event of school violence. These include establishing emergency operations plans, hardening the school building to prevent intrusion, and conducting security and risk assessments.

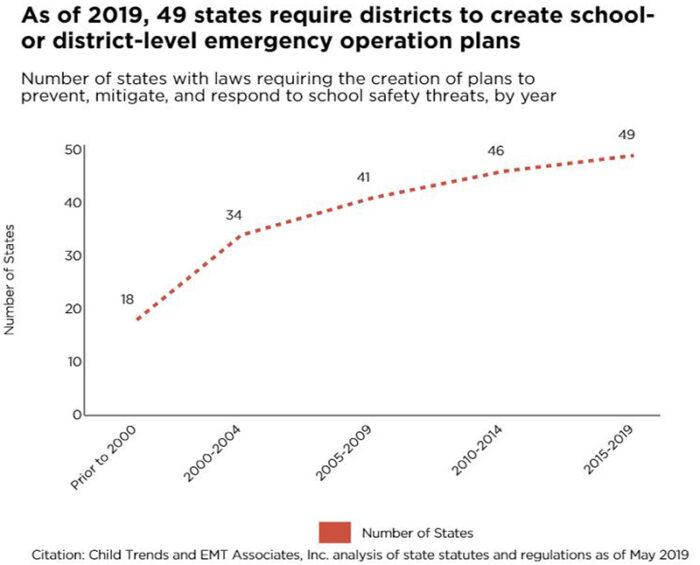

Emergency operations plans (EOPs) serve as guiding documents for local efforts—including coordination between schools and community partners—to prepare for severe violence, natural disasters, and other emergencies. Forty-nine state laws require the creation of district- or school-level EOPs to guide school actions to prevent, mitigate, and respond to safety threats. The U.S. Department of Education’s Guide for Developing High-Quality School Emergency Response Plans32 recommends that plans be developed at the building level for each school. Twenty-three states require districts to create school-level plans, while 26 require district-level plans only. The two remaining states—Hawaii and North Dakota—do not establish legal mandates in either statute or regulation to create school or district safety plans. Thirty-nine states require districts to review and update their emergency plans periodically, consistent with best practices, and more than half of those require annual updates. The remaining 12 states with school emergency planning laws do not require districts to regularly review or update school safety measures once plans have been developed and implemented.

The first state to mandate the development of a comprehensive safe school plan was California, in 1989.33 The authorizing legislation represented an approach to crime prevention on public school campuses, although it also addressed emergency and disaster preparedness.34 Ten other states established laws addressing school safety planning prior to 1999, and 13 states passed such laws in 1999 and 2000. By 2012, 19 additional states enacted school emergency response and crisis management statutes or regulations, with three more (Connecticut, Kentucky, and Montana) in 2013 and the remaining three (Iowa, Kansas, and Wyoming) in 2018.

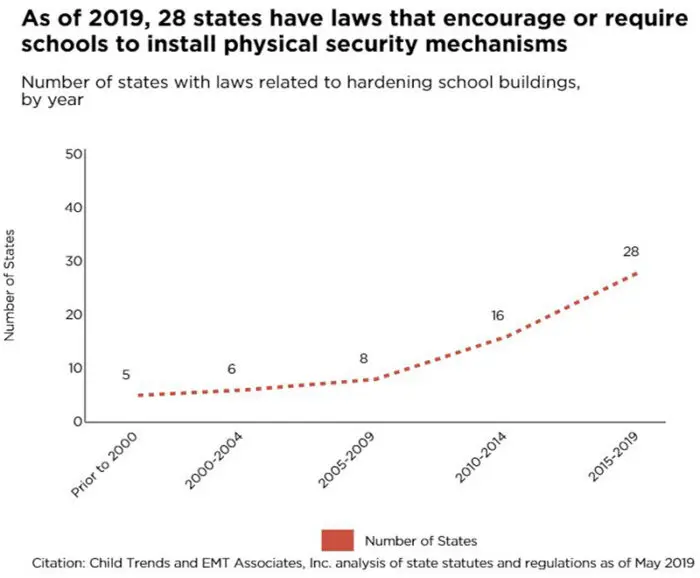

Hardening the school building refers to installing physical security mechanisms to prevent the entrance and advancement of an armed intruder. Such mechanisms can include access control systems, video surveillance, metal detectors, classroom and building locks, and other protocols. Research is limited as to the effectiveness of such measures on improving school safety.35 While some research indicates that certain hardening protocols, such as external video surveillance, may increase perceptions of safety, other protocols, such as internal video monitoring, may decrease perceptions of safety and students’ feelings of connectedness to school.36

As of 2019, 28 states have provisions in their laws relating to hardening school buildings,37 including building code requirements, authorizations of funding to support school hardening improvements, and guidelines for security measures in schools. Most laws specify the types of hardening procedures, including building locks, access control, and panic systems. Georgia’s law allows districts to request funding for security upgrades, “including, but not limited to, video surveillance cameras, metal detectors, alarms, communications systems, building access controls, and other similar security devices.”38

New York (1994), Oregon (1995), Delaware (1996), Virginia (1997), and Pennsylvania (1999) had the earliest laws referring to hardening procedures, which were generally much less prescriptive than later laws. For example, Oregon’s law, which has not been amended, simply requires schools to maintain doors that can be opened from the inside without a key.39 Most states with school hardening laws passed them after 2012, with seven states adding laws from 2013 to 2015 and nine adding them in 2018 and 2019.

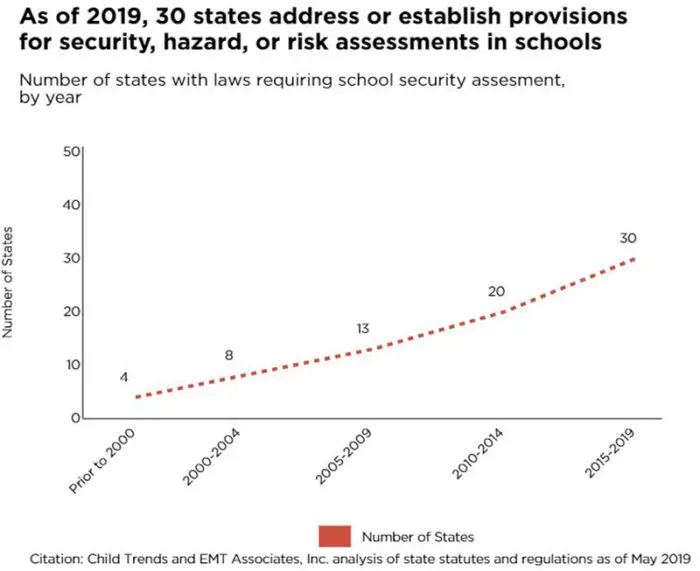

Risk assessments help schools identify and mitigate potential security vulnerabilities. As of 2019, 30 states address or establish provisions for security, hazard, or risk assessments in schools. Such laws are often paired with the development of EOPs and often specify both the frequency of such assessments and the agencies that must be involved in assessment execution or review. Colorado requires annual inspections to “address the removal of hazards and vandalism and any other barriers to safety and supervision.”40 Other states have instead created tools and technical assistance to support schools in conducting risk assessments. For example, Kentucky recently updated its 2000 law to require schools to conduct a security assessment, create a risk assessment tool, and provide training for school administrators.41

In 1995, South Carolina passed the first law requiring a school security assessment, followed by Oregon (1996), North Carolina (1997), and Virginia (1997). Most laws addressing risk and security assessments were passed after 2012, with eight states adding laws from 2012 to 2016 and six states in 2018 and 2019.

Active Shooter Preparedness

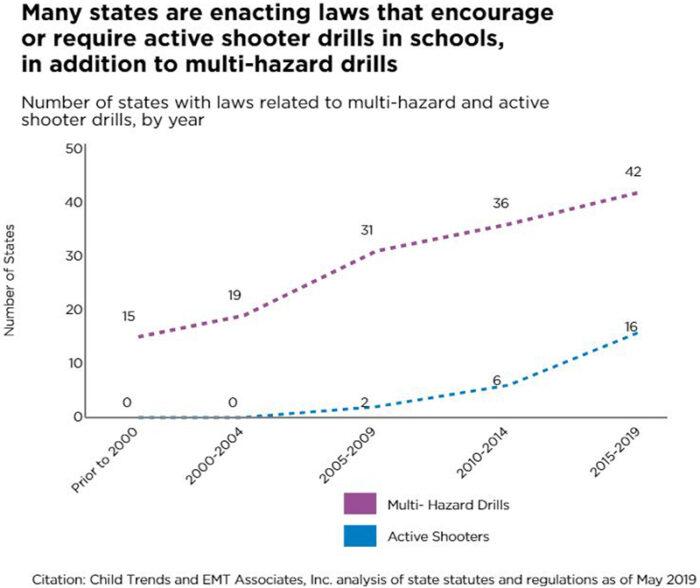

Prior to 1999, most states already had laws or regulations mandating the implementation of practice drills to prepare schools for fire or natural disasters. However, after the Columbine shooting, states incorporated more detailed and prescriptive mandates to expand and enhance practice drill requirements—for example, by requiring a variety of functional drills, such as lockdown, shelter-in-place, and evacuation drills.

As of 2019, 42 states encourage or require districts to implement such multi-hazard drills.

The FSSC report notes that states are moving toward including drills specific to active shooter or armed intruder events. As of 2019, 16 states encourage or require active shooter drills, 10 of which passed following the Parkland shooting. Ohio passed the earliest law requiring active shooter drills in 2006, followed by Indiana in 2007.

The FSSC report notes that states are moving toward including drills specific to active shooter or armed intruder events. As of 2019, 16 states encourage or require active shooter drills, 10 of which passed following the Parkland shooting. Ohio passed the earliest law requiring active shooter drills in 2006, followed by Indiana in 2007.

Summary

Twenty years after the Columbine school shooting, state policymakers continue to refine policies in an attempt to improve school safety and security. With each school shooting, policymakers establish new laws and regulations in the hopes of avoiding another tragedy. Using the FSSC recommendations as a framework, this brief explored seven issue areas in state-level policies. While policymakers continue to refine their approaches, many current proposals were already firmly embedded in state laws prior to the Parkland shooting in 2018. Still, that incident—as with many other major shootings of the past two decades—seems to have spurred considerable policy making, particularly around the FSSC’s recommendations related to protection, mitigation, and response. Although many states have also enacted laws related to the FSSC report’s more prevention-focused recommendations—including laws related to character education and school climate—both the timing and content of these laws have generally been unconnected with efforts to respond to school shooting events.

Still, some laws and policies have evolved to recognize the need to integrate and align efforts to promote safety and security with initiatives to maintain supportive school environments that remain focused on student learning and well-being. This is particularly evident in the growth of laws that better define the roles of school-based law enforcement and require training to ensure that the presence of officers does not lead to adverse consequences for students, as well as in the growing integration of laws that address school safety with those addressing student mental health and positive school climates. This promising trend recognizes that the threat of school violence often emerges from within the school itself, rather than from an external threat.44 It further expands the notion of school safety from a mere defense against an attack to preventing one in the first place.

Although some policymakers are moving toward this holistic understanding of school safety, many are still calling for expansion of school security laws without consideration of the existing policy landscape. Such a consideration should include both an assessment of how existing laws have been working and of how such laws may contradict broader efforts to support the “whole child” (including efforts around character education and school climate). This is particularly evident in the rapid expansion of laws requiring schools to implement active shooter drills.

The existence of a state law does not mean that schools or districts are implementing that law as written or intended. Our current analysis only examines whether states have school safety provisions in statutes and regulations, but not whether those laws have been well understood or implemented by districts and schools or whether they have reduced school violence. More work is needed to understand how provisions in state law have translated into practice in schools and to evaluate such policies’ relative effectiveness.

Methodology and Data

The research, coding, and analysis method used to formulate this policy brief builds on a previous methodology developed by Child Trends, the Institute of Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and EMT Associates, Inc. for the January 2019 Using State Policy to Create Healthy Schools report. The report and policy brief are two products in a series of deliverables developed under a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Together for Healthy and Successful Schools Initiative.45 The larger policy report assessed coverage of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Whole School, Whole Child, Whole Communities (WSCC) policy framework, which includes 10 interrelated WSCC domain areas: health education; physical education and physical activity; nutrition environment and services; health services; counseling, psychological, and social services; social and emotional climate; physical environment; employee wellness; parent engagement; and community involvement. Comprehensive state policy responses to school safety and security issues cross-cut several of these domains, including physical environment; social-emotional climate; counseling, psychological, and social services; and parent and community engagement.

To assess the history of state school safety policy efforts, we collected state statutes and administrative regulations for each of the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia using Boolean keyword searches in Lexis Advance and Westlaw commercial legal databases. We identified school safety-related statutory and regulatory provisions enacted or amended as of May 2019, with an emphasis on policies enacted from 1999 forward, and documented the legislative histories of each statute and regulation to assess the emergence of specific policy trends in state laws and regulations. To analyze the content of identified statutes and regulations, we developed a coding rubric across 15 core school safety domains that align with seven sections of the FSSC report that have direct implications for school practice.

The larger report describes the current policy landscape within each safety-related domain, reporting the number of states that do or do not address various provisions in law and documenting the timing in which certain provisions first appeared in state statute or regulation. The brief does not assess whether such policy strategies have been effective at addressing or reducing school violence; rather, it focuses on what supports currently exist in state law and how such supports were established.

Endnotes

1. DeVos, B., Nielsen, K. M., & Azar, A. M. (2018). Final Report of the Federal Commission on School Safety. Presented to the President of the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/documents/school-safety/school-safety-report.pdf

2. Ibid 1.

3. Ibid 1.

4. Gulbrandson, K. (2018). Character education and SEL: What You Should Know. Seattle, WA: Committee for Children. Retrieved from: https://www.cfchildren.org/blog/2018/07/character-education-and-sel-what-you-should-know/

5. Ind. Code Ann. § 20-30-5-6 (2005).

6.Md. Code Ann., Education § 7-306 (2013).

7. Tex. Educ. Code § 28.002 (1995 & Supp. 2019).

8. Horner, R. H., et al. (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(3), 133-144.

9. Ibid 8.

10. Stuart-Cassel, V., Bell, A., & Springer, J. F. (2011). Analysis of State Bullying Laws and Policies. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/bullying/state-bullying-laws/state-bullying-laws.pdf

11. Cullen, D. (2009). Columbine. New York: Twelve.

12. Moore, K. A., et al. (2015). Preventing violence: A Review of Research, Evaluation, Gaps, and Opportunities. San Francisco, CA: Futures Without Violence. Retrieved from: https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/preventing-violence-a-review-of-research-evaluation-gaps-and-opportunities

13. Ibid 12.

14. Acosta, O. M., Tashman, N. A., Prodente, C., & Proescher, E. (2013). Establishing successful school mental health programs: Guidelines and recommendations. In H. S. Ghuman, M. D. Weist, & R. M. Sarles (Eds.), Providing mental health services to youth where they are: School and community-based approaches (pp. 57-94). New York & London: Brunner-Routledge.

15. S.C. Code Ann. § 59-66-40 (2014).

16. 19 TAC § 129.1045 (2017).

17. Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., Sawyer, M. G., Scales, H., & Cvetkovski, S. (2010). Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC psychiatry, 10(51). doi:10.1186/1471-244X-10-51

18. MCLS § 380.1308b (2018).

19. O.C.G.A. § 20-2-1185 (1994 & Supp. 2018).

20. U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center. (2019). Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Secret Service. Retrieved from: https://www.secretservice.gov/data/protection/ntac/usss-analysis-of-targeted-school-violence.pdf

21. National Association of School Psychologists School Safety and Crisis Response Committee. (2014). Threat Assessment for School Administrators and Crisis Teams. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Retrieved from: https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/school-climate-safety-and-crisis/systems-level-prevention/threat-assessment-at-school/threat-assessment-for-school-administrators-and-crisis-teams

22. Va. Code Ann. § 9.1-184 (2019).

23. Rev. Code Wash. (ARCW) § 28A.320.127 (2013 & Supp. 2016).

24. Maryland Safe to Learn Act of 2018 Md. SB 1265 (2018).

25. Exstrom, M. (2019). School Safety: Overview and Legislative tracking. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved from: http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/school-safety.aspx

26. James, N., & McCallion, G. (2013). School Resource Officers: Law Enforcement Officers in Schools. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43126.pdf

27. Miller, M. & Jean-Jacques, W. (2016). Is School Policing Racially Discriminatory? Washington, DC: The Century Foundation. Retrieved from: https://tcf.org/content/commentary/school-policing-racially-discriminatory/?session=1&session=1

28. Rev. Code Wash. (ARCW) § 28A.320.124 (2019).

29. School Safety and Student Well-Being 2019 Wa. HB 1216 (2019).

30.Ind. Code Ann. § 20-34-3-23 (2018).

31. R.R.S. Neb. § 79-2,144 (2014 & Supp. 2017).

32. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students. (2013). Guide for Developing High-Quality School Emergency Operations Plans. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://rems.ed.gov/docs/REMS_K-12_Guide_508.pdf

33. Cal Ed Code § 32282 (1985).

34. 1989 Cal AB 450

35. Jonson, C. L. (2017). Preventing school shootings: The effectiveness of safety measures. Victims & Offenders, 12(6), 956-973. doi: 10.1080/15564886.2017.1307293

36. Johnson, S. L., Bottiani, J., Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). Surveillance or safekeeping? How school security officer and camera presence influence students’ perceptions of safety, equity, and support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(6), 732-738. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.008

37. This count includes legislation passed by Kansas in 2019 that has not yet been codified into statute.

38. Ga. Code Ann. § 20-2-1185 (2010).

39. ORS § 336.071 (1995).

40. Colo. Rev. Stat. § 22-32-109.1 (2000).

41.Ky. Rev. Stat. § 158.445 (2018).; Ky. Rev. Stat. § 158.4410 (2019).; Ky. Rev. Stat. § 158.442 (2018).

42. Rygg, L. (2015). School shooting simulations: At what point does preparation become more harmful than helpful? Children’s Legal Rights Journal, 35(3), 215-228.

43. Hamblin, J. (2018, February 28). What Are Active-Shooter Drills Doing to Kids? Washington, DC: The Atlantic. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/02/effects-of-active-shooter/554150/

44. Ibid 35.

45. Chriqui, J., et al. (2019). Using State Policy to Create Healthy Schools: Coverage of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Framework in State Statutes and Regulations, School Year 2017-18. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. Retrieved from: https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WSCCStatePolicyReportSY2017-18_ChildTrends_January2019.pdf

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube