Creating partnerships: Learning new ways to connect

Note: This essay also appears on the website of the Knowledge Network for Applied Education Research.

Over the last two decades there has been a steady growth of high-quality research in education and human services. Yet we have heard researchers express frustration that policymakers and practitioners don’t use (and sometimes misuse) research findings. Conversely, policymakers and practitioners suggest that research is frequently not relevant to their work-or it’s not easily accessible or understood. This is not surprising as evidence-based practice and policy has traditionally been about producing evidence and disseminating research to users—an approach that Vivian Tseng has characterized as a one-way street.

But just producing rigorous research and bringing evidence to practitioners and policymakers won’t get it used. Users need ongoing engagement around research. They need opportunities to talk about the research and interact with others to apply findings. Researchers need to focus less on dissemination and more on dialogue. Enter research-practice partnerships.

Long-term collaboration between researchers and decision makers—research-practice partnerships—shift the dynamic between research producers and users by creating two way streets. Instead of asking how researchers can produce better work for practitioners, partnerships ask how researchers and practitioners can jointly define research questions. Rather than asking how researchers can better disseminate research to practitioners, partnerships strive for mutual understanding and shared commitments from the beginning. Successful partnerships enable researchers to develop stronger knowledge of practitioners’ challenges, their contexts, and the opportunities and limitations for using research. And they allow practitioners to develop greater trust of the research and deeper investment in its production and use.

The Principles Behind Successful Partnerships

While there are many different kinds of RPPs, they are guided by key principles that make them different from other types of collaborations.

Mutualism brings researchers and practitioners to the table to develop an agenda that is mutually beneficial. By collaborating throughout the process, both researchers and practitioners get their needs met.

Commitment to long-term collaboration means that the partnership can foster iterative work to understand and address key problems of practice. There is an ongoing cycle of learning and doing.

Trusting relationships are the key to effective partnerships. To sustain a long-term collaboration, partners need to believe that they can rely on each other to come through on agreements and to understand and even anticipate each other’s needs and interests. Trust enables partners to weather bad news, disagreements, unfulfilled expectations, and changes in leadership.

How do Partnerships Work?

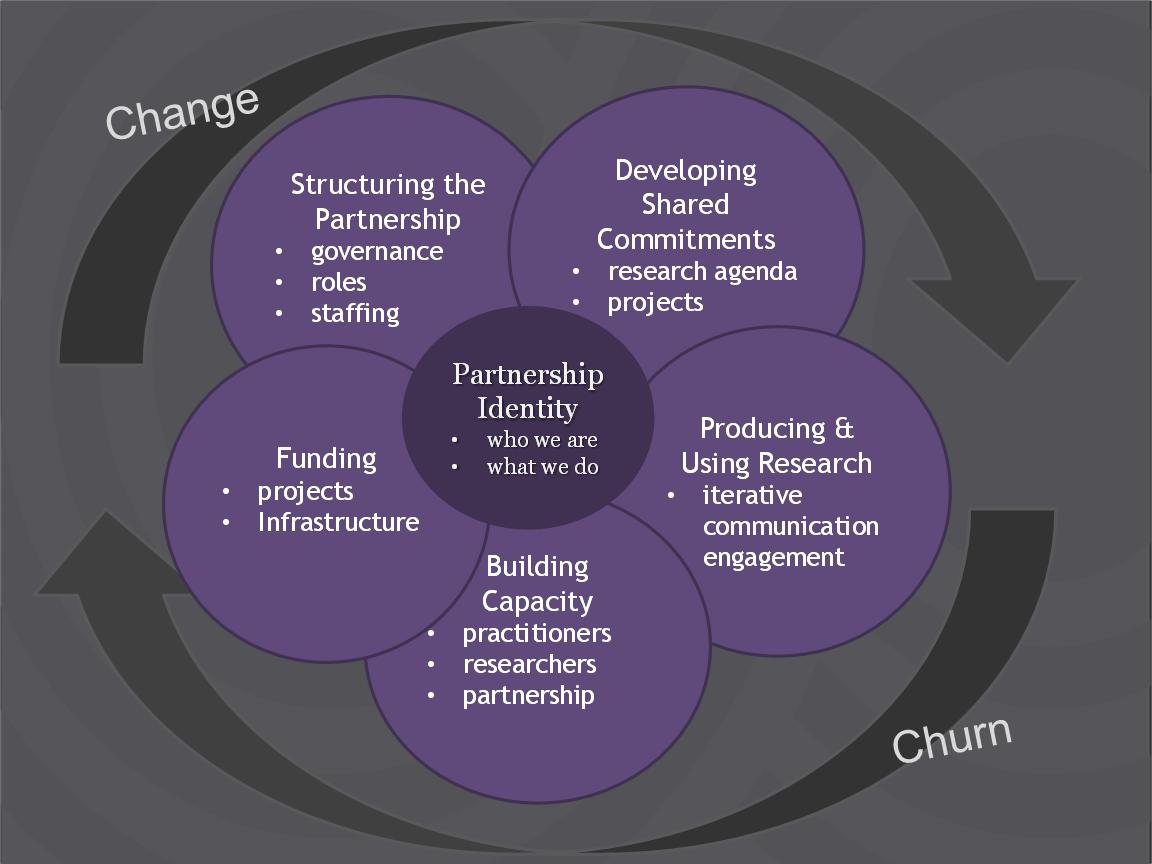

Building an RPP is hard work. They are complex organisms, with structures, processes, and roles that evolve as partnerships mature and adapt. However they form, we have observed five elements that seem to come together in successful partnerships. (See Diagram 1)

- All RPPs must determine their structure. While not all RPPs have formal documents, many develop charters, MOUs, and operating principles to record their shared goals, clarify stakeholder representation and roles, and spell out governance and operational issues.

- RPPs must develop a shared commitment, which includes defining the research agenda. The research agenda is a focal point for activities within a research–practice partnership. In RPPs, research agendas are shaped around problems of practice, policy, and implementation, and are co-shaped by partners to fit practice priorities.

- Partnerships need to develop their processes, routines, and “ground rules” for producing and using research evidence. Many RPPs have a “no surprise” rule, wherein the agency partners have an opportunity to review a research report before it is released to the public.

- Capacity building may involve one or all partners in the collaboration. It can focus on building the agency’s capacity to use research, bolstering researchers’ capacity to conduct and communicate useful research, or supporting the capacity of the partnership itself through staffing.

- It’s critical that the funding portfolio for RPPs covers partnership infrastructure as well as projects.

As all of these elements come together, a partnership identity often emerges where research and practice partners develop a shared sense of what their partnership is and what it does.

The University of Chicago Consortium on School Research’s (CCSR) 25-year relationship with Chicago Public Schools illustrates how a school system can learn from research evidence to drive improvements over time. In the late 1990s, CCSR researchers sought to measure freshman progress toward graduation and developed an “on-track indicator” to help schools identify freshmen who were unlikely to graduate in four years. Their research challenged prevailing assumptions and stimulated new ideas for combating dropout. But the work didn’t stop there. The district and schools put systems in place to use the indicator data to intervene with students while their research partners experimented with user-friendly ways to present the data. As schools tried out different strategies for bringing students on track, CCSR systematically studied those strategies to determine which ones worked and why. By 2013 that sustained work had yielded an on-time graduation rate of 82 percent, up from 57 percent just six years earlier. Educators, using data and research, learned how to better support student success.

Let’s turn to a relatively new partnership between the research and program offices within one agency: the Office of Family Assistance’s (OFA) healthy marriage programs and the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE)within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (ACF). In the early 2000’s, OPRE launched long-term studies to evaluate whether marriage and relationship education programs might improve outcomes for children in low-income families. By the time the evaluation results were available-about ten years later-the context within ACF had changed and the program office had new questions, not envisioned when the long-term studies were planned. A misalignment had emerged between what research could offer and what current policy needed. In order to make the research more relevant, closer collaboration between the research and program offices needed to be established.

That’s exactly what happened when in 2010 a partnership was structured between OPRE and OFA’s healthy marriage programs. Lauren Supplee, formerly of OPRE, and her OFA counterparts sat down and discussed the needs of the program. Since they had a history of working together, they already had a trusting relationship. Subsequently, they were able to structure a partnership that would be responsive to OFA staff. One way that this took shape was that OPRE researchers invested time in building relationships with OFA acrossall levels of staff. By working together, ideas for new research projects are generated through the year. To build the research agenda, the OPRE and OFA staffs have ongoing conversations about program operations as well as specific structured meetings around annual research planning. The overall goal for these discussions is to raise questions from the field that research may be able to support. The research portfolio now includes multiple projects that include foundational projects to describe services and participants, impact studies to determine efficacy of components or whole programs and research capacity building for the field to address important questions simultaneously. Through shared goals, shared commitment, open communication, capacity building and infrastructure, an effective RPP was born.

How can we Ensure the Next Generation of Partnerships

RPPs represent a sea change in the way we think about research, practice, and the uses of evidence. They break down walls between researchers and practitioners by creating two-way streets of engagement. Researchers and practitioners, alike, must remain open to learning about and adapting to different perspectives. Taking the long view on research and practice improvement reaps tremendous benefits for youth and families.

There are important questions that researchers need to ask themselves before entering into an RPP. Can they adopt new ways of working in order to produce more timely and useful research? Are they open to taking on different approaches to research? Finally, are they willing to acquire skills that are not traditional for researchers, including communication with broader audiences and imagining research agendas from a practice perspective?

Practitioners too, will need to work in new ways. They may need to ask themselves: are their organizations flexible enough to foster the conditions that will allow for more effective and systematic use of research evidence? At the same time, policymakers will need to address the bureaucratic barriers to research-program collaborations within agencies and between public agencies and external research partners.

Private and public funders have a role to play as well in preserving the progress that partnerships have made. While funding for projects is easier to come by, some foundations are not as willing to invest in operating costs and infrastructure development. But, RPPs need resources for outreach, communications, and relationship building if they are to be sustained for the long haul. What would be ideal is a reliable combination of funds: government support for operating costs and specific large-scale research studies, private support for infrastructure maintenance and behind-the-scenes internal “R&D” activities, local foundation support for context specific research and evaluation studies and infrastructure, and university support for faculty time and partnership space.

Research-practice partnerships are not the path for the faint of heart. But acknowledging and addressing the challenges inherent in the work can bring about opportunities to close the notorious gaps between research and practice—to build two-way streets that improve work on both sides of the divide. RPPs allow researchers and practitioners to build joint, strategic research agendas, to embed data and research in ongoing work, to build knowledge from one project to the next, and to integrate lessons learned into practice and policy. When mutual trust forges confidence in the research, we can collectively bring about more effective services and enhance outcomes for children and youth.

Lauren H. Supplee, PhD, Program Area Director, Early Childhood Development.

Vivian Tseng, Vice President, Programs, The William T. Grant Foundation.

John Q. Easton, Vice President, Programs, The Spencer Foundation.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube