The share of children in foster care living with relatives is growing

This blog was updated on May 24, 2019.

Nationally, one-third (33%) of children in foster care at the end of federal fiscal year (FY) 2017 were in a relative foster home. Current practice in child welfare is to prioritize placements with relatives over non-relatives. While research that examines the effect of living with a relative on children’s well-being is not conclusive, many child welfare practitioners and advocates agree that placing a child with relatives can reduce some of the trauma of being removed from the home. Relative foster homes are a valuable resource as the number of children in foster care increases and agencies across the country struggle to find enough family-based foster care settings.

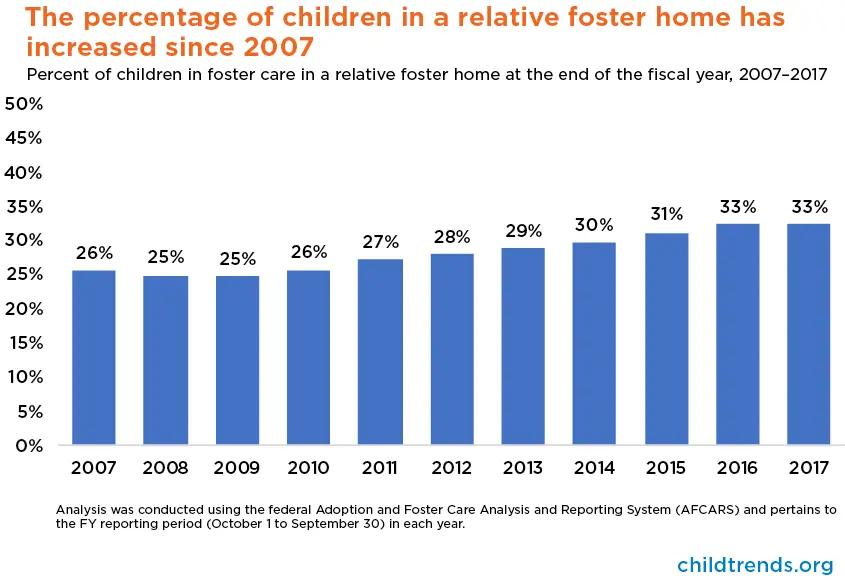

The percentage of children living in a relative foster home has risen by 16 percent since FY 2007, due in part to federal legislation that has facilitated this type of placement. With the passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018, which also promotes relative foster homes, this upward trend will likely continue. A similar trend can be seen in the growing share of grandparents caring for their grandchildren among the general population. The opioid crisis is likely a common factor influencing rates of relative care both within and outside of the child welfare system.

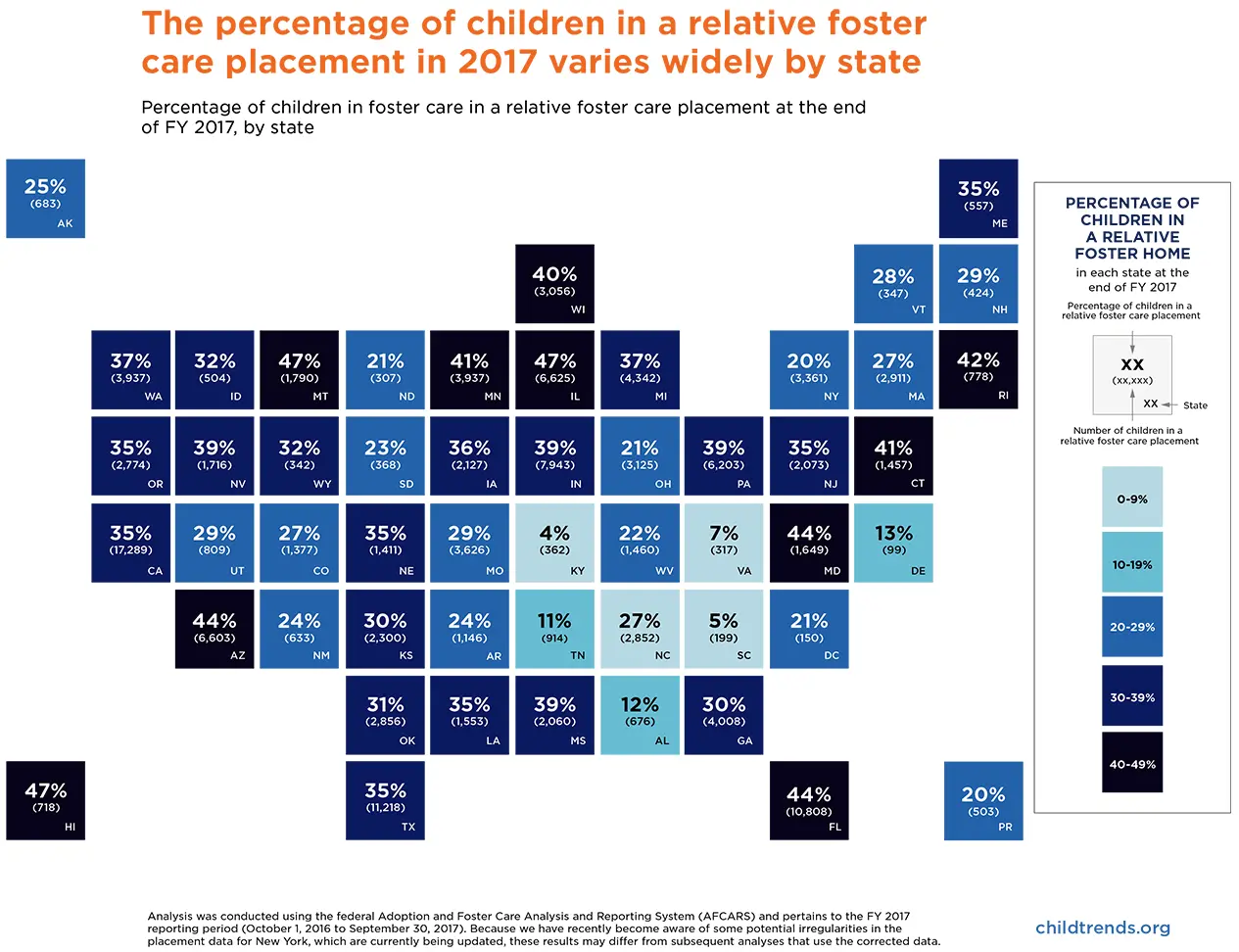

Child Trends’ analysis of FY 2017 data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) shows that the percentage of children living in a relative foster home at the end of the fiscal year varies widely across states (from 4% in Kentucky to 47% in Hawai’i). The five states with the highest percentages were Hawai’i, Illinois, Montana, Arizona, and Maryland. Kentucky, South Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama had the lowest percentages.

State policies can significantly influence the percentage of children in foster care who are in a relative foster care placement. For example, some states require relatives to be licensed foster caregivers to receive financial assistance and other supports and services they need to care for the child. However, a relative who needs such assistance but cannot meet common licensing standards (e.g., square footage requirements in the home) may not be approved as a foster care placement for the child. Inconsistent implementation of relative search and engagement policies (e.g., locating and notifying the child’s relatives of their entry into foster care) can also contribute to state-level variation. Relatives who are not notified about a child’s involvement with the child welfare system (as required by federal law) or engaged in case planning are less likely to be considered placement options.

The use of voluntary or informal kinship care arrangements, often referred to as “kinship diversion,” can also influence the number of children in relative foster homes. In states that practice kinship diversion (like Virginia), a child who might otherwise formally enter foster care and be placed in a relative foster home is diverted and placed with relatives outside the system—usually without court oversight. Child welfare practitioners and advocates are divided about the use of kinship diversion. Proponents argue that children are better off when they live with family, outside of the system, without the uncertainty often associated with government involvement. For example, relatives who care for children in the custody of a child welfare agency often relinquish control over aspects of the child’s care and daily life. However, others are concerned that, when children are diverted away from the child welfare system, they lose necessary safeguards (e.g., court oversight); in addition, struggling parents may go without needed services and supports, and relatives are not fully informed of all potential options and services.

At the national level, children placed in a relative foster home experience greater placement stability than those in non-relative homes, meaning that they stay in one placement instead of moving from home to home. Among children in relative foster homes, 54 percent experienced only one placement during their current stay in foster care, compared to 38 percent of those in non-relative foster homes. This stability is important since experiencing multiple placements can negatively affect children’s mental health.

Permanency, which the Children’s Bureau defines as having a permanent legal family, is a key child welfare outcome. When appropriate, reunification of children with their biological parents is the preferred permanency outcome; other permanency options include guardianship or adoption. Nationally, of children who exited foster care in FY 2017, those whose last placement was in a relative foster home achieved permanency at rates similar to those in non-relative homes (85% compared to 86%). However, the two groups achieved permanency in different ways. Children in relative foster homes were less likely than those in non-relative homes to reunify with their parents (46% compared to 61%), but more likely to exit to guardianship (29% compared to 10%), most commonly with a relative. While the financial burden of providing a permanent home can be an obstacle for relatives, most states now have subsidized guardianship programs that enable more relatives to provide a permanent home for children. These programs provide monetary assistance to relatives who are licensed as foster parents and become legal guardians for eligible children. The increased availability of subsidies likely contributed to the increase in the percentage of children exiting foster care to a guardianship arrangement among children placed with relatives (21% in 2007 compared to 29% in 2017).

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube