Children Still Left Behind 50 Years After War on Poverty

Author

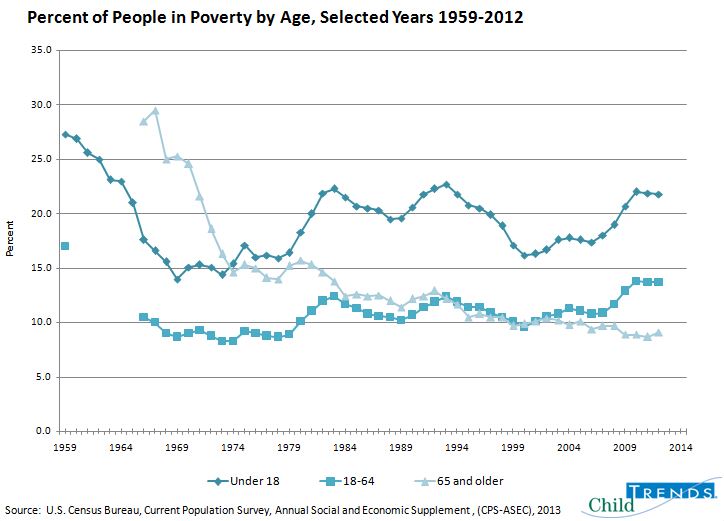

Fifty years after the War on Poverty was initiated, the youngest Americans continue to be our nation’s poorest. In 2012, more than one in five children (22 percent) lived in poverty, compared with 14 percent of adults ages 18-64, and 9 percent of adults ages 65 and older.

While child poverty rates for children have fluctuated since the 1964 rate of 23 percent, today they are nearly as high as they were 50 years ago. In 2012 (the most recent data available), nearly one in 10 children lived in extreme poverty, defined as having a household income less than half of the poverty threshold (currently $23, 550 for a family of four). Poverty is even more prevalent among children under five: one in four in 2012, as noted in Child Trends’ recent report on America’s infants and toddlers.

These wearying facts have been recited many times, but given all we know about the detrimental and long-lasting effects of poverty on children, they bear repeating. Research finds that poverty experienced early in life, sustained poverty, and extreme poverty are associated with particularly negative outcomes for children. That so many children experience poverty in their earliest years, the most rapid period of brain development, is especially troubling. Children growing up in poor households are more likely to be unhealthy, drop out of school, have chronic health problems as adults, and earn lower wages than those not poor during childhood.

As we noted in a 2009 Child Trends brief, childhood poverty saps our economy by reducing productivity and output, increasing rates of crime, and adding to health expenses. Given its importance, how can we reduce poverty among children? Safety-net and tax subsidy programs have been effective. For instance, Census Bureau analyses of the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which accounts for tax subsidies, in-kind benefits, and out-of-pocket expenses, found that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (commonly referred to as SNAP or Food Stamps), reduced the child poverty rate by three percentage points.

Poverty rates are highest among children born to young parents, particularly those with low levels of education. Efforts to delay childbearing should be considered a poverty prevention strategy. Teenagers and young adults would benefit from additional time to complete schooling, gain work experience, and build their earnings capacity, before taking on parental responsibilities.

In addition to prevention efforts, policymakers might invest in programs that promote children’s cognitive, social, and physical development, which may help to buffer some of poverty’s negative effects. Ensuring that poor children and their families have access to high-quality early childhood programs, home visiting programs, SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and other effective programs could go a long way toward reducing poverty and minimizing income inequality. According to Child Care Aware of America, costs for full-time center care for a four-year-old, compared to the poverty level for a family of three, account for anywhere between 25 and 86 percent of family income, depending on the state.

Fifty years ago, President Johnson, in declaring the war on poverty, called on Americans to “replace despair with opportunity.” Breaking the poverty cycle is critical to providing every child the opportunity to succeed in school, work, and life. Our country’s long term economic success depends on a healthy and well-trained and well-educated workforce.

For more research, see our resources on child poverty here.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube