Child poverty declines even as disparities persist among the nation’s youngest children

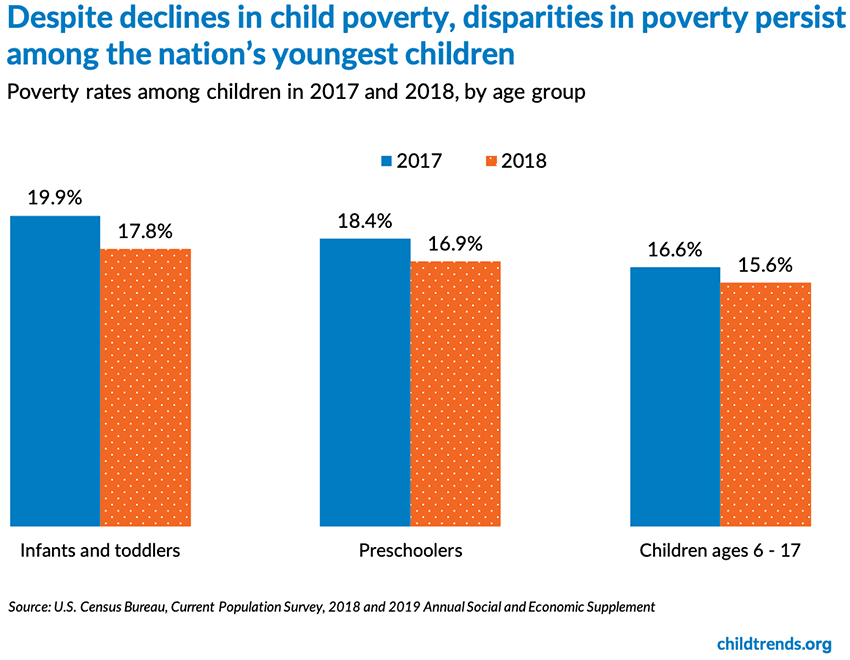

The most recent Census data show a small decrease in the poverty rate among the overall U.S. population, from 12.3 percent in 2017 to 11.8 percent in 2018. While poverty rates among young children (birth to age 5) also declined, this age group had the highest poverty rates, as it did in 2017. In 2018, an estimated 17.8 percent of all infants and toddlers in the United States lived in poverty, compared to 16.9 percent of preschoolers (ages 3 to 5) and 15.6 percent of older children (ages 6 to 17).* Poverty rates were highest among infants and toddlers (birth through age 2), Black and Hispanic young children, and young children living in single parent-headed households—particularly female-headed households—relative to children without these characteristics, suggesting that the benefits of improved economic conditions were not equally distributed across families.

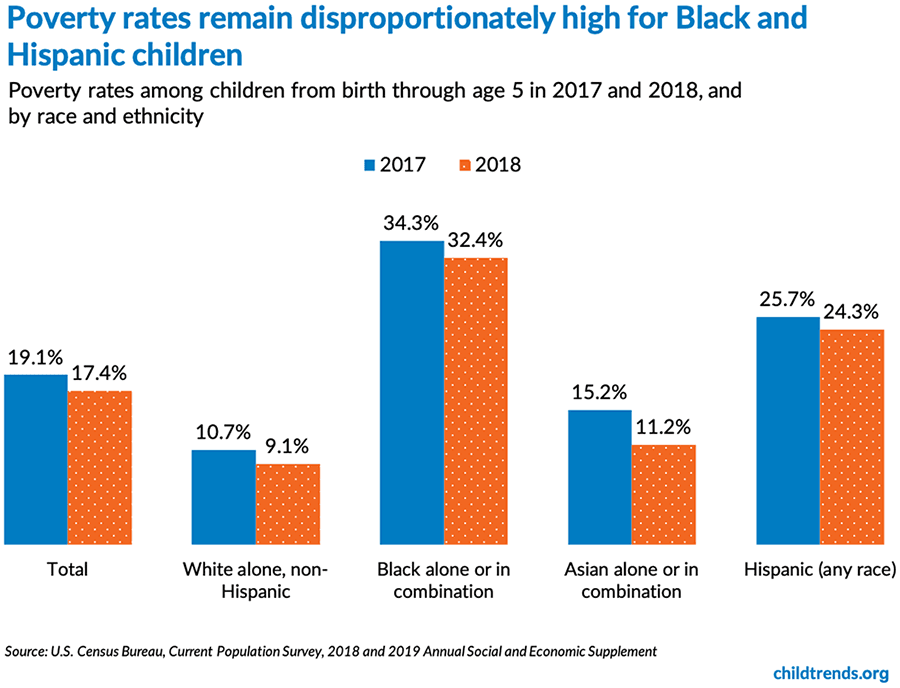

While poverty rates remained the same or decreased slightly from 2017 to 2018 for all racial and ethnic groups, the poverty gap between young Black and Hispanic children and their white peers under age 6 increased. Despite an overall decline in poverty rates from 2017 to 2018, nearly 1 in 3 Black children (32.4%) and 1 in 4 Hispanic children (24.3%) were living in poverty in 2018, compared to less than 1 in 10 white children (9.1%).* In 2017, young Black and Hispanic children experienced poverty at rates 3.2 and 2.4 times higher, respectively, than their non-Hispanic white peers; in 2018, young Black and Hispanic children lived in poverty at rates of 3.6 and 2.7 times higher than their non-Hispanic white peers.*

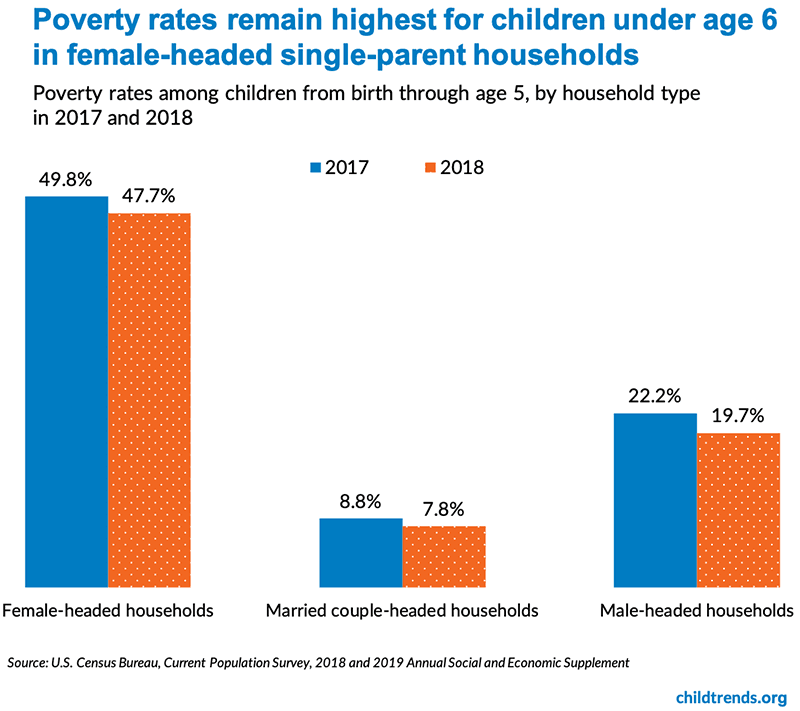

Census findings on poverty and household composition are also concerning for young children. In 2018, almost half of young children under age 6 living in female-headed, single-parent households (47.7%) were poor, compared to less than 1 in 10 of those living in a married couple-headed household (7.8%).* By comparison, poverty rates were lower among young children in male-headed, single-parent households (19.7%), but considerably higher than for a child in a married couple-headed household.* These rates reflect a decrease from 2017 to 2018 (in 2017, 49.8% and 22.2% for female- and male-headed households, respectively), yet clearly show that young children with single parents remain at high risk for experiencing poverty.*

In fact, even though overall poverty rates have gone down, the poverty gap between female-headed households and two-parent households increased from 2017 to 2018. In 2018, young children in female-headed households experienced poverty at rates 6.1 times higher than their counterparts in married-couple households; in 2017, their rates were 5.7 times higher.*

Even as overall child poverty rates have declined, poverty remains a serious problem for many children, especially infants and toddlers, young Black and Hispanic children, and children living in female-headed, single-parent households. In particular, these subgroups of young children are disproportionately likely to experience poverty and are at especially high risk for adverse outcomes associated with poverty, including chronic illness, poor school achievement, and financial instability across multiple generations. Policies to address these inequities are essential to advance population health, particularly as our country becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, and as household composition and parenting responsibilities for young children change and grow.

* Analysis conducted by Child Trends. Data source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

© Copyright 2024 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInThreadsYouTube